Absurdist Theatre and Resistance

I have been reading. Always a fan of the absurdists, I have been reading them particularly closely for the last few months. I have been looking for clues, looking for pathways. I have been trying to listen to voices of those who have come before.

My older brother started reading me Ionesco when I was seven, so I have a head start. But for many years, I saw these plays as a warning from the past, not a guide for the future. Now I see both. I am grateful, and I am scared.

Absurdism is about facing a world in which nothing seems to make sense… It is about the embracing the fact that our lives can be both terrifying and ridiculous, indeed the more terrifying, the more ridiculous. And it is about resistance.

When I started my theatre company in the 1990’s, absurdism was considered passé. To New Yorkers, it seemed to most a remnant of a past era, connected vaguely with wartime. I was also a fan of Václav Havel, but that too was a different world, a world of communist bureaucracy under the Iron Curtain, far away from here. When I put together the Ionesco Festival in 2001, more than a few people asked me: Why here? Why now?

I didn’t have an answer at first. Then 9/11 happened.

Absurdism is about facing a world in which nothing seems to make sense. It is about accepting that deeply tragic events happen sometimes without much or any warning. It is about the realization that our understanding of the universe is limited and flawed. It is about the embracing the fact that our lives can be both terrifying and ridiculous, indeed the more terrifying, the more ridiculous.

And it is about resistance.

Martin Esslin, author of Theatre of the Absurd, the book that helped define the movement, credits Alfred Jarry’s Ubu plays as some of the earliest in the absurdist tradition. Clearly, they are ridiculous, mocking the idea of sane authority by placing a man of the worst appetites in the role of leader. They are innately revolutionary in their anti-establishment tone. Yet they lack the sense of tragedy later absurdist works carried. They are the early twentieth century’s South Park, a cartoonish satire that gains power from transgression. It seems little coincidence that Cartman so resembles Ubu in form and manner.

The resemblance to our new President has of course been widely noted in theatrical circles.

The first great absurdist, according to Esslin, was Samuel Beckett, and here we have the tragedy Ubu lacked. In Beckett’s spare words and blasted landscapes was the anguish that came from having just lived through a world at war. Beckett himself was a member of the Resistance in Paris. Many of his comrades were arrested. The spirit of the perseverance through despair permeates the work he wrote. His resistance was simple. “You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

It is a mantra I have repeated to myself often these last few months.

Eugene Ionesco brought a more anarchic spirit, closer to Jarry’s. Yet he too was heavily influenced by the war. He called his work tragic farces, with an emphasis on the tragic. Rhinoceros, of course, was a direct response to the rise of fascism, but also a critique of the human tendency to put ideology above critical thought. Ultimately his answer to resistance was the one embodied by his hero, Berenger, heroic not because he chose not to mindlessly follow the masses, but because he was simply incapable of doing so. The end of Rhinoceros finds Berenger lamenting his inability to be anyone other than himself.

In a world fractured into ideological bubbles, where truth is defined by so many as whatever confirms their existing biases, the need for independent thought is greater than ever.

Jean Genet’s defiant work loudly decried the social order he lived in. Genet also lived through the war, but the battles he chose to write about were the ongoing battles of class, race, and sexuality. His resistance was ongoing, throughout his life and his work.

It is a resistance worth noting now the recent gains in LGBTQ rights are once again in jeopardy, when the questions raised by Black Lives Matter are being dismissed as invalid by those in power.

And then there was the work under the Iron Curtain. These playwrights were writing about a new absurdity, where words lost their meaning in a deliberate attempt to obfuscate truth. But it was also self-critical. Polish playwright Slawomir Mrozek’s Striptease took aim at the constant internal dissent among the revolutionaries, where differing approaches to resistance led to nothing but dithering and inaction.

That same internal strife and consequent inaction is an ailment I have seen around me often over the last few months.

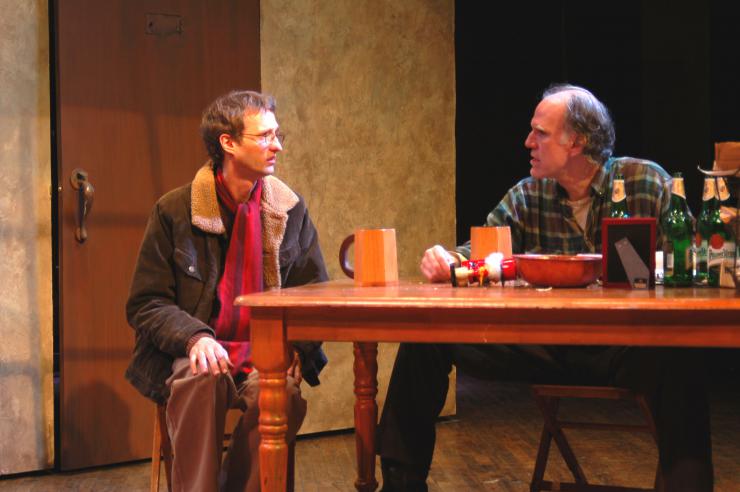

And Václav Havel, writing in Czechoslovakia, took aim at little lies that gave the government power. He warned against the normalization of those lies. His characters were often members of the resistance who were subverted into capitulation. His play Audience feels particularly resonant. It is a two-hander, a confrontation between a dissident playwright, forced to work in brewery, and the head of that brewery, charged by the government to spy on him. The essence of their absurdity is that each of them believes the other has the power.

The truth in Havel’s play mirrors what I think is an important truth for the resistance. Neither the blue-collar brewmaster nor the intellectual, elite writer are the ones in power. They both are victims of a larger system. The compassion Havel shows in his play for them both is a touchstone for me. It presents a way though the madness of modern politics, a way to reach out to those who seem unreachable.

When I produced the Havel Festival in 2006, with 9/11 safely behind us, I was asked again what relevance Havel’s work has for us today. I thought I knew then. But I didn’t understand fully how relevant it was, how relevant it will always be, until now.

Once a month, in my apartment, I have started to gather actors and other artists, and together we read. What will come of it, I don’t know. Maybe some understanding of resistance. Maybe a work that addresses the absurdism of today.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

"You must go on. I can't go on. I'll go on" is not a statement of resistance. It is not a stoicism. It is utter despair. It comes from "The Unnameable" and is a statement of the inability of humans to resolve into the pure Self, to transcend or end or step out of the Play. It is the moan of Belacqua in Purgatory. It is the realization by Beckett the writer that even though he does not wish to write. He cannot write. He must write. Everybody misunderstands that statement because they have not really read the three novels.

I've read The Unnamable. We have different interpretations of the ending. To me, it is a reiteration of his most common theme, the same that exists most of his dramatic work. In Godot, E & V probably should give up. Godot will almost certainly never arrive. They agree to give up. They don't give up. Is that resistance? In the way perseverance through horror is resistance, yes. But this is more subtle than stoicism. We don't give up because of something in our basic nature, even perhaps when we should. But of course, as with every great work, each reader can have his own interpretation.

"Havel took aim at little lies that gave the

government power. He warned against the normalization of those lies... His characters were often members of the resistance who were subverted into capitulation... Neither the blue-collar brewmaster nor the intellectual, elite writer

are the ones in power. They both are victims of a larger system. The

compassion Havel shows in his play for them both is a touchstone for me.

It presents a way though the madness of modern politics, a way to reach

out to those who seem unreachable."

Very well put. (I find myself thinking about Havel myself lately.)

Thanks. His Power of the Powerless is online, by the way, for those who want to read it https://medium.com/@bruces/...