Elegant Variation

The Nina Variations by Steven Dietz takes as its premise a replaying with variation of the final scene from The Seagull. Nina, an actress, returns to the town where she grew up. She meets Konstantin (a writer, the great love of her youth) in the family house she frequented when they were teenagers. Konstantin’s mother, a famous actress, has just returned to the house with her lover, the famous writer Trigorin, and they are in another room: we hear them playing on the piano and their glasses clinking. Two years earlier, Nina ran away from home (and the ardent lover Konstantin) with Trigorin, who soon abandoned her with his illegitimate child. The child died in infancy, and Nina has since been touring in the provinces with little theater companies of ‘ill repute’. Konstantin knows all of this news, but he has not seen Nina, who left him so abruptly, and for him tragically: he loves her still. Their scene together at the end of the play is their first meeting since.

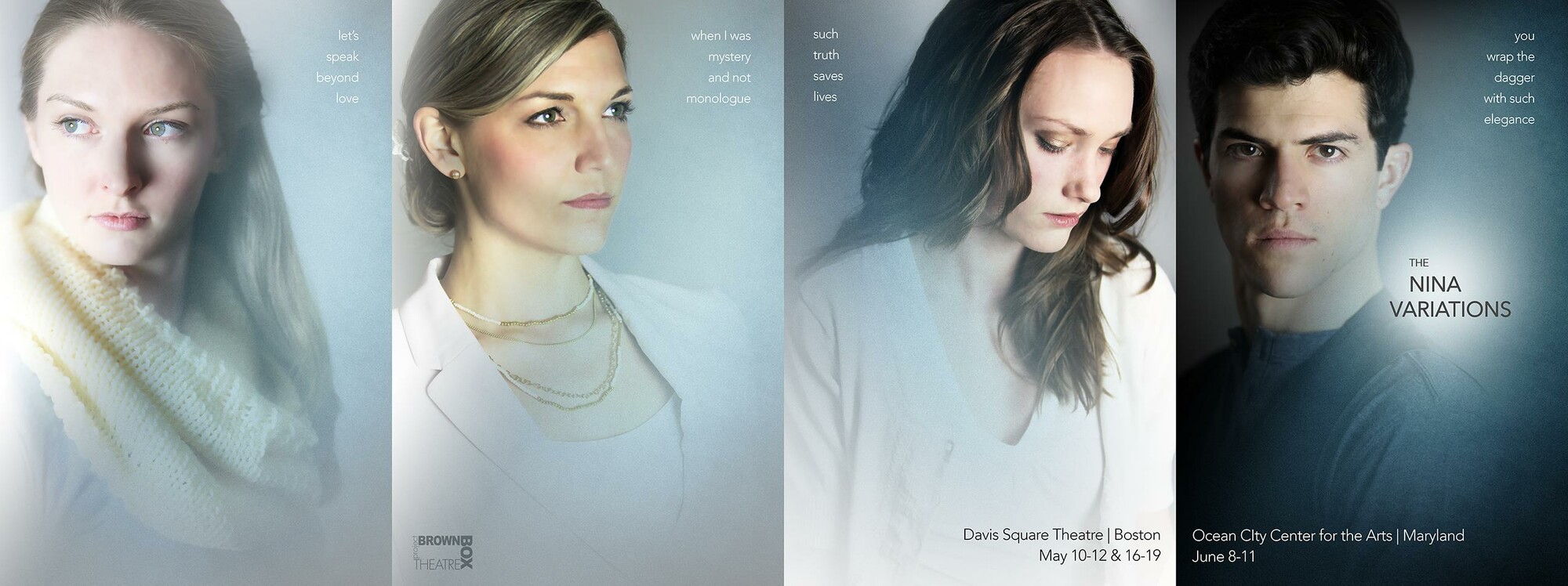

The scene, of course, is very famous, and I offer a glancing recap of it less to inform you, reader, of the plot than to admire the structure that supports it: there is reason for a writer like Dietz to hitch upon this scene. He had been commissioned to write an adaptation of The Seagull: “I could not focus on the rest of the play at all. I was mesmerized by the magnitude of this single fateful encounter,” Dietz has said. He never completed the adaptation. The Nina Variations, written in 1996 and much produced on the regional theater scene that Dietz has called his own, shows the playing-out of forty-three different versions of the “fateful encounter”, deconstructed perhaps, but certainly unmoored from the conventional passage of time.

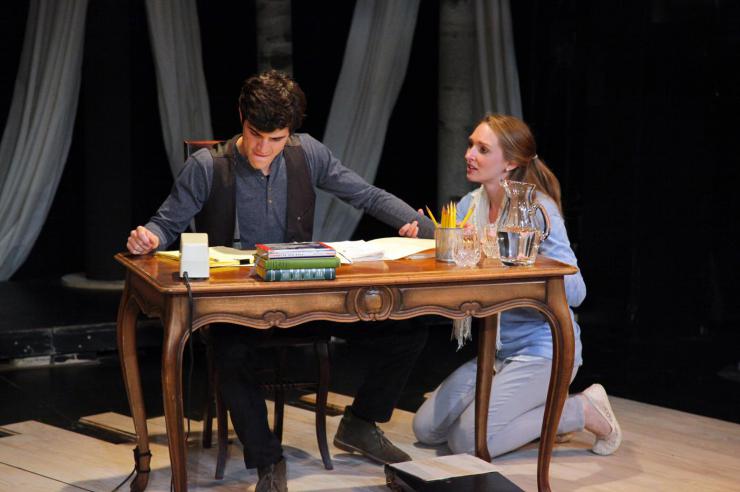

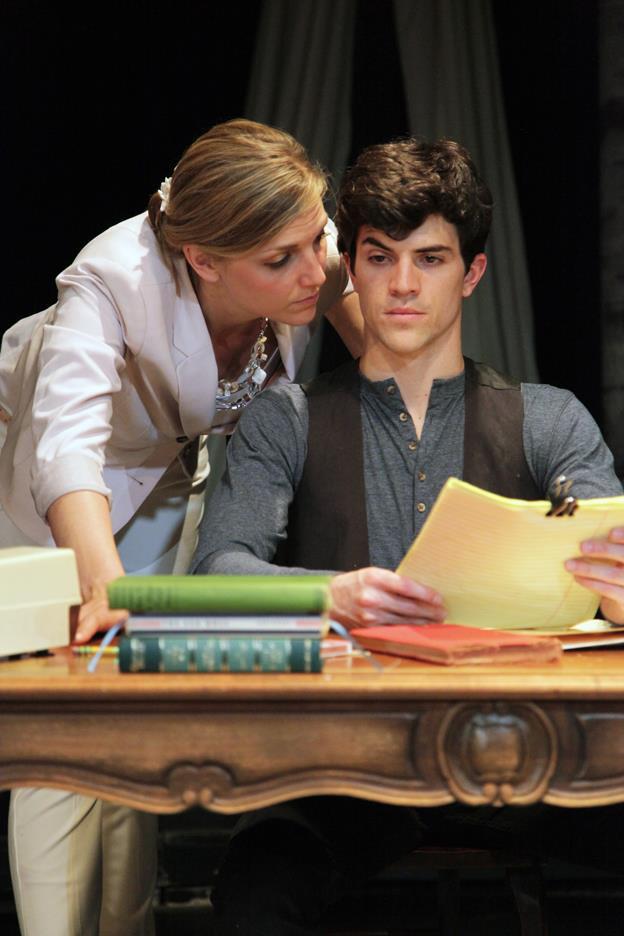

In Brown Box Theatre Project’s recent production of the play, the sense of variance is multiplied in casting: three actresses play the role of Nina, each with a certain energy and elegance that is delightfully watchable in ensemble. In ways, director Kyler Taustin has put the audience into Kostya’s predicament: though all three girls circle the space, engaging the architecture beautifully, one never does know how Nina will look when she next arrives, how her life has aged her in the fateful years that have passed, or what sort of woman she has become through her experience. She is literally someone else each time. Certainly this sense of realization is punctuated for us by an unpredictable order of appearance, and the wildly different energies folded into the room by Kara Manson, Laura Menzie, and Kate Paulsen—all as Nina.

The actors are meant to have no memory, except in ensuring that they reach emotional climax by a slightly different route, like trying every flavor of ice cream.

Manson brings a strange, soft elegance: dressed down, she seems at home in her maturity, as if finished with the feminine wiles that have brought her so much trouble. She revisits her old hometown with her sneakers on, no longer performing for anybody, but the shameless theatricality of some of her outbursts is Nina’s shameless theatricality: differently grounded, she casts around her for familiar territory in a performative zone, and overarticulates when she is upset, like an actress. We might recognize in Manson’s performance the arranged calm of a woman who will not be categorically defined as damaged. That normalcy is a state she must perform above some nameless dramatized energy makes her presence almost ghostlike, and deeply haunting.

By contrast Menzie is filled with life. Bounding through her scenes with a youthful vigor that will not relinquish easy, playful intimacy with Konstantin, her momentum is infectious, and she is positively funny. It is a relief to laugh in a play like this, and Taustin was lucky to find an actress who can treat serious material with such matter-of-fact vitality, eerie only in its dauntlessness. It throws us for a loop: one cannot imagine someone so charming and vivacious coming to an unfortunate end, or to anything like romantic failure: she is obviously the girl of someone’s dreams. Menzie’s performance actually deepens the play by articulating whole realms of optimistic possibility.

Kate Paulsen will make a terrific Arkadina when she is old enough for the role, and she carries with her a side of Nina that echoes Konstantin’s overbearing mother, also an actress. We see the articulated reasons for assuming such personality in Paulsen, who uses good taste, beauty, and a sense of superstition (just close enough to witchcraft) to go after her objectives. She is dressed to perfection, made up with all the care of a samurai warrior in her role as a flawlessly put-together woman, and it is in her voice that Konstantin is confronted with a kind of dark knowledge that he has not yet experienced. Where Manson’s delicacy keeps this engine to herself, Paulsen’s Nina initiates Konstantin into some other realm, and seems to insist that we understand. There is not necessarily optimism in her performance, but there is shimmering fatality to spare: it is she who seduces Konstantin, but without the sense that any good will come of it. It is a ritual they go through before parting, like all lovers.

And so, Juan C. Rodriguez as Konstantin is strung between three powerful women, like Macbeth, and comes to grief only in the impossible predicament of comprehending what his history with them ought to be. He is a charming performer, but how does he relate to the three when they are all to have been his one true love? Are their histories the same? They seem, for the girls, not to be. So Rodriguez, shouldered with the impossible task of creating coherence, is often successful, but sometimes falls short of utterly reinventing himself and his life’s tragedy in the half-moments between scenes. This is a shame, for the constant readjustment this forces on him does not highlight his capability: we wait for variation from the women while he plays catch-up. A terrific monologue about his relationship with Masha seems like pure invention from Dietz, but is a shining moment for Rodriguez: finally secure and speaking from his own experience, he sings with a refreshing spitefulness. One wishes after this, and for his sake, that the characters were set on more equal ground.

For me, this trouble with Konstantin’s coherence is not a problem with the actor (though it is surely a problem for the actor), but much more a problem of the play. What do we learn, I wondered, leaving the Davis Square Theater after the 90-minute performance, by revisiting this encounter so many times, even if it is well-acted and elegantly directed? Somehow, there is a sense of late-twentieth-century trendiness about the conception: a famous piece of dramatic literature, deconstructed and re-explored, because we now no longer present classics that have not been deconstructed and re-explored. Different interpretations are surrounded with a gimmick that turns back time, forty-three times. Nina’s struggle is given all sorts of voice from all sorts of feminist perspectives. You get the idea of all this just by reading the title of the play: The Nina Variations.

Dramatists were fascinated, during that brief period of the late 20th century, with the endless iterations of possibility. This play is somehow a distant cousin of David Ives’ Sure Thing, where a couple tries again and again to get together in a restaurant, and must re-try after each weak-willed concession, after each minor political incorrectness, after each failure to sympathize, after each bell rings. In a way, The Nina Variations is more perverse: Nina and Konstantin must try again and again, but we are not to laugh at that ridiculous arrangement, and their predicament will always end them in a cramped failure to achieve the giddy happiness that lends momentum in the Ives piece (which, it bears mention, is also very short). But we are not meant to come away from The Nina Variations with a Beckettian sense of the endless circus of repetition, either: time is not really circular here, it is diddling. If Rodriguez has difficulty breaking from his last moment, it is because he is not entirely meant to in the text. We are tempted to let these characters learn something in each stub of scene that might be applied to the next go-around, but not so much that that they can escape repetition: the actors are meant to have no memory, except in ensuring that they reach emotional climax by a slightly different route, like trying every flavor of ice cream. Each kind of revelation occurs for its own romantic swoon, whether it be a romantic swoon over coupling or glorious independence, but the swoon is not meant to go anywhere.

This sometimes produces something momentarily moving, but that is mostly because of the actors’ art, which could bring us further if they were given a real transformation to achieve, or a new event to produce. Instead, they are made to wallow in their difficulty in a repetition that lacks Sisyphus’ weird dignity or Beckett’s tragic and redemptive comedy: a repetition that is never really acknowledged by the play, but used as a transparency, as if it were obviously what needed to be done. It is not obvious. It seems like the players are suffering for fun, and we are asked to nurture our own adolescent urges to replay our own dramatic moments with such preciousness. At finish we are sick of ice cream. The writer has not used time responsibly.

In playing with chronology, this is what there is to lose: the simplistic fatality of time that marches irrevocably on, giving no opportunity for replays, better wording, variation. The Seagull seems to me a play that tells us something about this tragic and ridiculous quality of time, where Dietz was only mesmerized and troubled by it: always yearning for another turn that might end happily. The force of the scene, what has driven the playwright to groom it with such a fine comb, is that its manifestation always falls ridiculously short, without all the treasures of significance that it ought to have. This is like life. We do not find that kind of power in any elegant variation.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here