Holler

Gun Shy

Got issues? Of course you do. Keep’em coming—write to me at [email protected]. For previous Holler columns, go here.

Dear Holler,

Years ago when I was just starting my career, several actors and directors I knew were working with an up and coming company (now gone). One of those friends showed a play I'd written to a board member. He loved it; he thought it would be perfect for the upcoming season. He called me and I met him at the theater. We talked about the play, we talked about the company, he had even drafted a contract! He suggested we meet for coffee the next week. We had a great talk, but as we left he asked when we would "have some private time." I answered that we just did. Over the next few weeks he made it clear that he wanted to date me, and that the production was basically contingent on that. I turned him down with as much tact as I could muster. He didn't deserve that consideration, but he made his position as a decision-maker very clear and I knew that humiliating him would have consequences for me beyond just that company. The great interest in my "fantastic" new play vanished as soon as it had sunk in with this guy that I really wasn't going to sleep with him.

I haven't talked to any professional colleagues about the incident, not then nor since. I've never been told by a fellow writer, a director, a performer, or a designer that they've endured a "casting couch" overture. It is impossible that I'm the only person to experience this.

So, what's really going on? Is sexual harassment a given in the theater, and I'm just naive? How on earth is an artist supposed to handle this?

Sincerely,

Gun Shy

Dear Gun Shy,

Thank you for your letter. You should know that taking this step to reach out about what happened to you is so brave and so important. It is going to help you get past this ugly episode stronger and happier, and it will decrease the likelihood, even by %0.01 that someone down the line will go through this him or herself—and even if they do, you’re decreasing the likelihood that they’ll go through it feeling as alone as you did. You are turning your hardship into a gift, an opportunity for us all to get better, and that’s ’effin beautiful. Many aspects of your letter moved me, but one that really stood out was your observation that no one else has ever spoken to you about a “casting couch” nightmare, and yet the cliche exists... I share your hunch that it probably happens more than we realize, and yet we don’t talk about it. Why not? I think again you hinted at some of those reasons—fear of career damage, (wrongly) believing “this is just how it is in the theater,” and of course, our old friend Shame. Whatever the reason, it sucks that, in a field essentially built around human communication, you’ve struggled to find or create a community of support after an event like this.

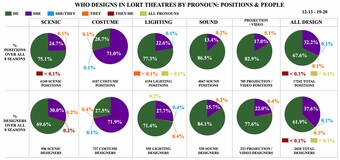

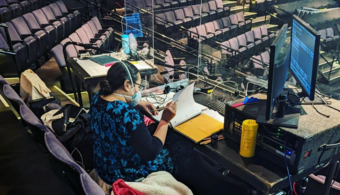

Your story illustrates the dark(est) underbelly of some of the issues that get lots of play here in HowlRound: the power dynamic between producers and artists, the fine (and easily exploitable) line between one’s work and oneself, and the often tricky terrain of navigating personal relationships (welcome or not) within a creative practice that demands vulnerability and exposure. Most of all, your story is a reminder that, even if theaters have all the outward trappings of professional institutions (boards, buildings, sexual harassment policies), it is not clear how well those workplace protections offered to full-time staff meet the needs of the great masses of freelancers waiting in the audition line, emailing the literary manager’s assistant, or having coffee with a board member. Often, a theater’s creative work is outsourced, and those folks (essentially, all temps) rarely have the same kind of recourse that even an job candidate at a law firm would receive if her superior behaved inappropriately. If an auditioning actor gets unwelcome advances from a director, but he really needs the job, he accepts it anyway. He likely won’t go public—as you point out, doing so could cause serious career damage, especially because he has no guarantee the theater where this incident took place will back him up.

The Bottom Line: A theater's community extends further than its weekly payroll list—if your staff or leadership prey on artists using institutional access as cover, you've got a problem, and you must fix it.

This is a serious question for our community: If you run a theater, you take care of your employees. You take care of the artists currently working on a production. You even take care of the audience when they’re inside the building. But what are you doing to take care of the actors trying to get cast, the playwrights trying to get read, the directors trying to get hired? No, you may have no legal responsibility here, but in a very real sense, those would-be employees are your community, too. They might be next season’s artists—they might even be some future season’s artistic director. Make them feel welcome—go to the audition waiting room and meet them. Stay in touch with the director you didn’t hire for your last show. You can’t offer them health insurance, but making them feel part of the institution doesn’t cost a cent.

The reverse is also true. Gun Shy didn’t suffer from a lack of attention from the theater’s leadership—quite the opposite. But your responsibility to your theater's extended community of artists still applies. If you have a board member running amok, drafting bogus contracts while asking for dates, you have a leadership problem, and you are responsible. A freelance artist like Gun Shy has nowhere else to turn—she or he needs to remain in the theater’s good graces, and complaining about a board member is hardly a way to do that. A theater must be a good citizen itself, and it must promote good citizenship among its staff and leadership. Every member of the team represents this specific theater, and, by proxy, the theater field itself. (Where do you think that casting cliche came from in the first place? From it happening! Probably a lot!). Any board member who does what this one did either thinks this conduct is ok or knows it’s not ok and doesn’t care. Either way, you don’t want this person representing you in the community, no matter how big that annual gift is.

But back to you, Gun Shy. You asked three questions: Is this a given in the theater? Are you really alone? And how is an artist supposed to handle this? Your final question strikes me—how is an artist supposed to respond, as opposed to a dental hygienist or a shepherd.

At the end of the day, this is a story about your integrity. It’s about who you want to see when you look in the mirror. And if I could wax for a moment, it’s a story about who we as a field want to see when we look in our (collective, metaphorical) mirror. I could spend hours listing all the ways this producer wronged you, wronged his or her theater, possibly broke the law, and generally acted like a scumbag, but I’d rather focus on the immense, inspiring power of your moral compass. As I often say here, each of us has an individual responsibility to make this field a place we’d want to work. By placing your self-respect over your ambition, you did just that. Fully aware of the professional risks you were taking by turning him or her down, you chose the more honorable path. “Honorable” can be pretty lonely, as you soon discovered, as sadly our field frequently rewards certain kinds of negative behavior—the tendency to inappropriately blend the personal and professional chief among them. Did it cross your mind, in the days after you turned him down and the theatre stopped being interested in your play, how many other plays in that theatre’s season slept (or flirted) their way into the calendar? What about the other theaters in your town, or across the country? Sadly, actors are not the only theater professionals getting objectified. And yet, in that moment (and presumably since), you made a decision.

Somewhere in that decision, I believe, is your artist DNA. So, you ask, how does an artist respond to this kind of unwanted attention? An artists responds as an artist—the only artist they truly can be.

You’ve made it through this stronger and smarter, and it sounds like you outlasted this theater anyway. Now you get to write a play about it (or a TV treatment, let’s be real here). You get to laugh about it with your colleagues (changing names if you wish). And by doing so, you get to be the colleague another friend comes to with a similar story, and then you get to be the one to help him or her take the best action. But most of all, someday, when you are in a position of power and influence (as I am sure you will be), you will get to model the kind of community-building, respectful, loving treatment towards artists that you were denied this time around. You get to make this a field you'd want to work in. And, even better, this enlightened state will make you such a magnetic, charismatic person that you won't have to resort to sleazeball tactics to get yourself a date. Everyone wins!

Love,

Holler

The Bottom Line:

A theater's community extends further than its weekly payroll list—if your staff or leadership prey on artists using institutional access as cover, you've got a problem, and you must fix it. If you're on the receiving end of this BS, don't just shrug it off—You don't need any gig that forces you to compromise your integrity. Instead, let your integrity guide you—and the rest of us—into building a better community.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Sexual harassment against an applicant for employment is prohibited under Federal law and most, if not all, state statutes as well. For some basic information on the Federal law, see http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/ty.... Additionally, a theater may have contractual obligations (with a Federal, State, Foundation, School, etc. grant) whereby they agree not to discriminate based on sex, among other things. Those contractual obligations may cover situations where the anti-discrimination laws don't apply. Since sexual harassment is generally considered a category of sex discrimination, sexual harassment could have adverse ramifications under those grant contracts. Anecdotally, there are numerous examples of theater staffpeople who lose their jobs because of their sexual harassment actions -- but there is a great deal of sexual harassment that does not get reported, for all the reasons that you mention.

Dear Dan -- Thank you for making this important point! Often I think auditioning actors fail to see themselves as "job applicants", even though that's exactly what they are. And playwrights, designers, and directors might have a tough time understanding when they are or aren't actively applying for a job because the social/professional line is so often blurred. But it's a good reminder that there are some laws in place to protect those not yet employed by an organization. Thanks, Holler.

The sources of this awful behavior begin early, sometimes in undergraduate and graduate theatre programs, modeled by faculty members. There are places where this isn't tolerated anymore, but sexual "joking" -- often with subtext that goes far beyond a joke -- seems to be a long and unfortunate tradition in the theatre and students learn the behavior early. That's the place to start fixing the problem. I probably don't need to add that Hollywood overflows with this issue.

Theatre Bay Area published an article on sexual harassment in theatre a while back. It's an important issue and theatres should definitely adopt a zero tolerance policy that they talk about w/their board and artists. http://www.theatrebayarea.o...

Dear Gun Shy,

You are not alone! You are SO not alone.

Out-and-out harassment, demeaning wisecracks, or guff for behavior that's only acceptable in men have all come my way, and the way of many, many women, (and a few men) I know in my town. Some of us have buckled, some moved on, some have sued for damages or resorted to blackmail-between-'friends', (or, 'fair play', as I was told.)

Holler's answer rightly gives you credit for concern and courage while addressing the reality of fluid power dynamics in our business. Setting and respecting your own boundaries re acceptance and action is the surest way to a sane, centered response.

Finding the strength and wisdom to do so gets so much easier when the cycle of silence is broken. Find others in your community who you trust enough to share with while you map the best course for yourself.

Meanwhile:

YOU ARE NOT ALONE.

Dear Gun Shy,

You are not alone! You are SO not alone.

Out-and-out harassment, demeaning wisecracks, or guff for behavior that's only acceptable in men have all come my way, and the way of many, many women, (and a few men) I know in my town. Some of us have buckled, some moved on, some have sued for damages or resorted to blackmail-between-'friends', (or, 'fair play', as I was told.)

Holler's answer rightly gives you credit for concern and courage while addressing the reality of fluid power dynamics in our business. Setting and respecting your own boundaries re acceptance and action is the surest way to a sane, centered response.

Finding the strength and wisdom to do so gets so much easier when the cycle of silence is broken. Find others in your community who you trust enough to share with while you map the best course for yourself.

Meanwhile:

YOU ARE NOT ALONE.

May I also suggest that playwrights -- even student playwrights and fledgling playwrights -- strongly consider joining the Dramatists Guild. It's a wonderful thing to have someone to call up and ask advice when you need it, whether it be on a contract or a situation you're unsure about. They have actual lawyers on staff, to help with legal matters. You don't have to go it alone. That "strength in numbers" thing is real.

~Ellen

______________________

EM Lewis

[email protected]

www.emlewisplaywright.com

______________________

This has happened to me SEVERAL times now, and each time, I've been instructed to "use it" (either as material in my own writing, or to pimp myself out to get ahead in general) and "keep quiet" since apparently "nobody likes a whistle-blower."

The people who've assaulted me are considerably more famous and more powerful than I'll ever be; I'm a perpetual intern, and currently looking for work AGAIN because I refuse to coast on whoever has grabbed me in inappropriate places. There's got to be a way to get a job as a woman in theater without becoming my own pimp; there just has to. Either that, or there has to be a way to get justice. We're a modern world; these pinching chauvinists should be more than just slapped on the wrist.

This is so important. I recently spoke with a colleague at another theater who was embarrassed and upset by a remark made by a supervisor from a different department. I pointed out that what had actually happened was sexual harassment - I also wanted to shout, "Girl, you'll be a woman soon! Welcome to the club!" But, jokes aside, it was depressing to me that 20 or so years into my career, this is still happening and still not immediately named as what it is.

Will she report it? I don't know. I hope so, but I also know there are systemic reasons in place for her not to.

We joke and pal around, and that is part of who many of us are, and also part of networking. But, we often fail to realize, especially with our younger colleagues, upcoming artists, and interns/apprentices that there is a power dynamic in play. Everywhere I have been on staff has had a sexual harassment policy, but place I work now is the first place I have worked that has a fully staffed, professional HR department.

Rarely have I heard of anyone making a complaint. We are afraid to be labeled as bad collaborators, so we try to laugh these things off, especially early in our careers, but also when we are striving in our career to achieve leadership positions.

While I am not sure we are really so different from other businesses, in theater we make excuses for bad behavior because the lines between friendship, work relationships, and the hierarchies are or seem fuzzy - I fell in love with my supervisor when working in a theater box office, and we are still together 17 years, 4 states, 1 cat, and 1 kid later. That, however, was quite a different story than being an 18 year old intern, getting my ass pinched, my clothing commented on, and being barraged by questions about my sex life by a Tony award winning artistic director. I sucked it up, too. 25 years later, those things shouldn't be happening, and when they do, we must not suck it up. I am also seeing the insidious effects of institutionalized sexism that women artists in particular face. I'm sure many men have experienced the belittlement of harassment, but I can only speak for myself. And, when I have spoken for myself (don't even get me started on being a parent much less a mother in this world), I have been accused of being a humorless bitch, not a team player, and worse.

We should all be pinky-swearing to take better care of each other so we can take better care of ourselves. Breaking into the professional theater world is difficult enough, no one should stand for it being humiliating, or, criminal.