Poetic Drama, Guerilla Opera

Giver of Light is a new opera. It is also a liberal adaptation of the life of the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi. It is set in a landscape that is a plastic and suburban generalization from the late capitalist American Midwest.

One of the things to be said about poetry is that it creates a space where form is content

Though incongruous elements are de rigueur in this the era of dramatic mash-up, I found this tripartite cocktail enticingly unwieldy. I sometimes describe the sinking feeling I get about productions that seem to be built on one idea: a Midsummer Night’s Dream so much about hippie drug culture that the complexity of the language falls away, or any kind of adaptation that rests upon a thought framed like this: “We all know Romeo and Juliet die at the end. But what if they didn’t!” This is not to say that fine theater could not be produced from such premises, but the donnée is more suspect. If it is easy to predict what a production might be like, it becomes less necessary to see what it actually is.

Though the attribution is doubtful, one of the things to be said about poetry is that it creates a space where form is content. This seems simple before trying to think of what it would actually, practically mean—particularly in theater, where so many elements and people must be put onto the same page in the same space. Yet we can articulate by contrast. A badly-updated Midsummer divides its form and content: it might paste on modernization and sequined outfits to distract from some poverty of conception, and so can be snugly condensed to make perfect sense on a glossy publicity flyer. Giver of Light, condensed most simply, might make little sense on paper: the enormous traditional referents it draws upon (opera, Persian poetry, American suburbia) only come to be related in the piece itself. A work of imagination, its form is its content. And at Boston Conservatory’s Zack Box on the last evening of May, it made for a very fine piece of theater.

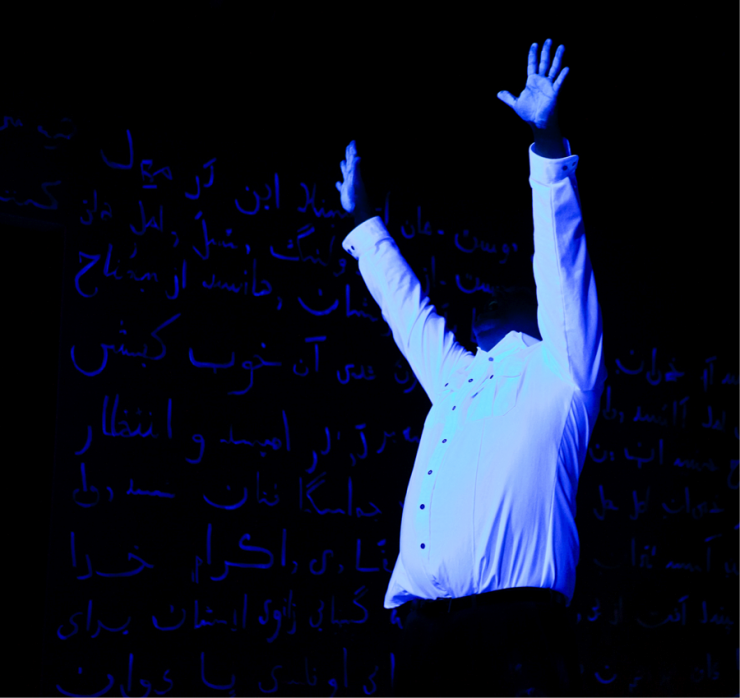

Jennifer Ashe, soprano (Brian); and Jonas Burdis, tenor (John).

Photo by Stephanie J. Patalano.

Composer Adam Roberts gives us a brief overview of Rumi’s story that so inspired him in his program note. Briefly, the myth goes that Rumi was a respected scholar, but was transformed by a friendship with Shams of Tabriz, a visiting mystic, who taught him to transcend book learning. With Shams, Rumi shared a particularly awakening and electric connection. It is rumored that one of the townspeople (perhaps one of Rumi’s sons), jealous of their friendship, murdered Shams—who at any rate disappeared. In longing for him, the scholar Rumi began to compose his poetry.

The story reported, Roberts goes on:

In deciding on a subject matter for my chamber opera, I felt that Rumi’s life story was particularly relevant for this time. We are living in an age of sound bites and cool detachment in which we cultivate our identities through social media alone in our rooms. We are more “connected” than ever before and perhaps more lonely. I can only imagine that people today must relate to Rumi’s longing for intensity. I certainly do.

He is more than correct. In 2007, Rumi was described as “the most popular poet in America,” and translations of his verse have been widely published, sold, and referenced by pop culture idols like Madonna. This is a particularly strange state of affairs given that his birthplace is deep in the regions that have so troubled and engaged American military and political focus during precisely the period when his poems have seen popular resurgence in English translation.

This circulating chain of history does not feel separate from what Guerilla Opera has created in Giver of Light. A whole sphere of interconnection appears in shadow-script on the performance like the Persian writing that is barely visible on set designer Julia Noulin-Mérat’s brightly painted walls, before the script glows with the magic of Tláloc López-Watermann’s lights. I learned from this production that opera is particularly suited to complex textual reference: details of the plot are traditionally included in the program, so we the audience know a good deal about the plot and its sources before the house lights dim. From there, the music takes over, and what we know about the story put simply is challenged by the sweeping experience of it.

What music it is! I should have liked the vocabulary of a music critic to address particulars of Mr. Roberts’ composition, which achieves richness with a small chamber ensemble of five instrumentalists and four vocalists, all situated onstage. A duet between John (the updated Rumi, played by Jonas Budris) and Darren (the bus-driver-mystic who stands in for Shams of Tabriz, played by Brian Church) develops the meditative om into a striking and textured aural illustration of the mind’s movement between true friends. This episode, with heavy use of electronic sound, is somehow superb and hallucinatory. It draws sharp contrast with scenes of John’s ordinary life, where plot points proceed in more or less bubbling, repetitious diction: “How was your day? How was your day? How was your day?” “It was good. It was good.” The quotidian drama played out at the kitchen table with John’s family (sopranos Aliana de la Guardia and Jennifer Ashe as wife Elena and son Brian, respectively) is perhaps more important than the meditative sequences to the unfolding action. But the quality here is different; comically impoverished on purpose. Though the matter of these scenes is more familiar, even their high drama begins to ring artificial; at least compared to meditation, less real.

Jennifer Ashe, soprano (Brian). Photo by Stephanie J. Patalano.

One of the frequently revisited motifs in director Andrew Eggert’s staging (elegantly supported by pops of primary color in Neil Fortin’s fine costumes) has the cast in transparent plastic masks, walking a grid around the space like automatons. Darren, the mystic, is not exempt from the grid-walk, or from the faltering exchanges that happen in normal diction. “My name is Darren. I drive this bus.” Wearing identity like a mask, each of the characters must inhabit the farce of real life’s problems and jealousies. That romantic tragedy occurs here for John’s wife Elena is particularly wrenching, as is her gorgeous aria in the second act, resonating the depth of de la Guardia’s vocal tone and her skill as an actress. For Elena the fragility of identity is revealed not by mystic experience, but by a loss of faith in her husband’s love. “Who am I? Who are you?” The pain of this is real; as wrenching as the arrest of Darren she soon orchestrates in a circus of misunderstanding that would be comic were it not heartbreaking and stupidly ridiculous—which as it turns out, this sexual jealousy is.

Jennifer Ashe, soprano (Brian); and Jonas Burdis, tenor (John).

Photo by Stephanie J. Patalano.

“If we would taste one sip of an answer, we could break out of this prison for drunks.” These are the first words sung in Giver of Light, and they echo in the longing note left to hang at its conclusion. Of course, this itself is not the sip of answer longed for: it is poetry, where the mad circus of life shares equal weight and stage-time with moments of transcendence, beauty stepping in apologetically for the happy resolution we might have liked. Such is the best we can hope for. And such is this fine little opera, Giver of Light.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here