Sport and Performance in Sochi

This series of articles accompanies PROPAGANDA: A Festival Celebrating Russian Voices. Through the lens of contemporary Russian theatre, the series spotlights Russia's recent anti-propaganda law in relation to sport, performance, and LGBT and Olympic history. The series is curated by Lauren Keating, the Festival's Producing Artistic Director.

Vladimir Nabokov, of Lolita fame, loved sport so much that he wrote an ode to the Olympics. And he said, “Everything in the world plays.” He felt that, from a juggler to a tennis player, when we engage in play, we harness the essence of the Universe. I must agree with him—and it’s no secret that sport and theatre are related. Far beyond entertainment, both offer community—as well as ways to test, examine, and deepen our expression and understanding of the human spirit. In the simplest of terms, sport is theatre with stricter rules and a focus on physicality, while theatre is sport with a focus on story, be it narrative or emotional. Actors and athletes embarking on professional careers encounter similar challenges, particularly: How much does my personality affect my career? Is my persona impeding or aiding my career? For actors and athletes who achieve widespread recognition, they must ask themselves, do I have a humanitarian responsibility?

With the spotlight of the Olympics upon them, athletes take center stage to compete. But, we don’t just want to see them race. We want to know who they are. We want origin stories and tales of overcoming incredible odds. We want myth. We want drama. Much like an actor builds a career, athletes build a story and legacy. Some, perhaps, do so naturally and without much thought about persona, but for LGBT athletes and artists, this process can be rife with the questions posed above. And, with the recent passage of “anti-propaganda” laws in Russia, this has never been more true, or more harrowing.

This year’s Winter Games will be held in Sochi, located on the coast of Russia’s Black Sea. On June 30, the Russian government passed the Anti-Propaganda Bill into law, making it illegal to promote “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations to minors,” meaning one cannot “distribute information among minors that 1) is aimed at creating nontraditional sexual attitudes, 2) makes nontraditional sexual relations attractive, 3) equates the social value of traditional and nontraditional sexual relations, or 4) creates an interest in nontraditional sexual relations.” What does this actually mean? Is it illegal for two women to hold hands? It’s unclear. There’s another bill currently on hold, put forth but then grudgingly redacted by Member of Parliament Alexei Zhuravlyov, that is likely to be reintroduced after the Games. This new bill will strip LGBT people of parental rights on the grounds of “nontraditional sexual orientation,” making it actually illegal to be LGBT and also be a parent, tearing apart loving families (both biological and adopted). Discrimination would be a polite term for these laws and what they accomplish.

It is true that Russia’s Anti-Propaganda Law, as it currently stands, is by no means the harshest legislation against LGBT people in the world, but as premier athletes of all cultures, creeds, and identities ready to gather in Sochi, some are making very difficult choices about persona, presentation, and humanitarianism.

The International Olympic Committee has forbidden protesting or statements about the law by athletes competing in Sochi—ignoring Principles 4 and 6 of their own charter. Principle 4 states plainly that, “every individual must have the possibility of practicing sport, without discrimination of any kind and in the Olympic spirit, which requires mutual understanding with the spirit of friendship…” and Principle 6 goes on to make crystal clear that “any form of discrimination…is incompatible with belonging to the Olympic Movement.” While the IOC’s stance is disappointing, events like those of the 1936 Games held in Nazi-ruled Berlin, Germany, or the more recent allegations of human rights abuses surrounding the 2008 Bejing Games, set an excellent precedent for willful ignorance. It is true that Russia’s Anti-Propaganda Law, as it currently stands, is by no means the harshest legislation against LGBT people in the world, but as premier athletes of all cultures, creeds, and identities ready to gather in Sochi, some are making very difficult choices about persona, presentation, and humanitarianism.

This past summer, my colleague Chad Callaghan, an actor, producer, writer, and athlete, was closely following the development of the anti-propaganda law and continuing to call attention to the dangers escalating for LGBT people in Russia. The International Olympic Committee was about to hold elections for a new president, and Chad and I saw an opportunity to impact the dialogue. We could throw up a gender-queered reading of a Chekhov play, raise some money for affected Russians and, most importantly, raise awareness about who should be elected the new IOC president.

Okay, so producing a quick reading is easy enough. Between Chad and myself, we’ve produced countless events and shows. But, trying to get information on what candidates to throw support behind and raise some noise for in the IOC election wasn’t so easy. In fact, getting information about what was really happening on the ground in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and beyond posed a challenge. And, it seemed impossible to actually get money into Russia to the newly homeless teens, whose LGBT safe houses have been shuttered in accordance with law. We kept digging. Brief articles, some personal and professional connections, passing conversations—it all started to amount to a network. Artists, activists, and athletes all engaged, all discussing the same issues, but not talking to each other. With opportunity for an even richer dialogue and greater impact, Chad and I saw we had a much bigger job to do.

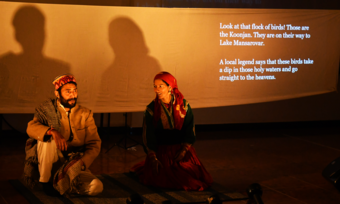

Thus, Propaganda was born: a weekend long festival giving voice to silenced Russian artists and creating dialogue between athletes, artists, and activists. This law is all about silence—don’t speak your truth, don’t live it in any visible way. So, we must fight it by spreading propaganda, by telling stories. Propaganda: A Celebration of Russian Voices—sparking dialogue, presenting incredible artists and giving actionable steps to improve the situation in Russia, during the Olympics and beyond. Cooper Union stepped up as co-sponsor, offering the Great Hall, which has a storied political history of its own. The Great Hall was the platform for some of the earliest workers’ rights campaigns, as well as the birth of the NAACP, the women's suffrage movement, and the American Red Cross. What could be a more perfect setting?

But, imagine living in a place that never had a women’s rights movement or a sexual revolution. Imagine living in a place that doesn’t have vocabulary to discuss those issues, let alone societal precedent.

Also a key early supporter was Kings Head Theater in London, having already commissioned playwright Tess Berry-Hart to write a docu-play about the anti-propaganda law. We agreed that the play, Sochi 2014, would be the culminating event of Propaganda. Tess interviewed a diverse array of Russians; not only victims of gay hate crimes, but also perpetrators. She spoke with activists, athletes, journalists, and policy makers—all in an effort to get the fullest picture of what was really happening in Russia. Tess is able to give incredible insight into the current situation. In the West, we tend to look at all countries as though they’ve been through our same national history, and have the same societal awareness and touchstones. But, imagine living in a place that never had a women’s rights movement or a sexual revolution. Imagine living in a place that doesn’t have vocabulary to discuss those issues, let alone societal precedent. Also, imagine this place actively rejects the West and is not seeking to be like us, but rather to distance themselves as far as possible from our example. Now try to start a conversation from that place.

Daria Wilke, Moscow-born and expatriated to Vienna, tries to do just that. Wilke wrote what is arguably one of the most quietly controversial books to be published in Russia this year. The Jester’s Cap follows a teenage boy as he discovers the man he’s long admired as the most skilled actor in his family’s puppet theatre, a popular and time honored tradition in Russia, is gay. Grisha, the boy, starts to discover how difficult the world is for his hero, Sam, and wonder if it will eventually be this way for him too. The book, like Wilke’s previous novels, is for a young adult audience. Well, this presents a problem, as her book now qualifies as “propaganda.” Rushed to press, it was able to be printed just before the law passed. But, it is now illegal for it to be read by its intended audience and has warning stickers slapped on the cover. And yet, The Jester’s Cap has been shortlisted for the Kniguru— a National Russian Prize for Best Book for Young Adults, awarded by the Center to Support National Literature. How is this possible?

It speaks to something I observed as a teaching artist, bringing Shakespeare workshops to under-represented people throughout New York. Hatred, or worse, apathy is most often a show. It can be a very necessary show, because it keeps a person safe. To admit caring about something, or to show an interest in something outside of the norm, makes you a target. It makes you vulnerable. It forces a person to do some quick math—do I think I can convince my peers to take an interest in this as well? Would I/we be able to turn the tide of public opinion? If not, how much is this worth to me? Is it worth people talking behind my back? Is it worth getting beat up? Is it worth my life? It so rarely is. And so, one puts on a mask of apathy, or joins the voices of hate, to hide the fear of being discovered as different or other, or simply because it’s easier. Or, in the case of Russia’s anti-propaganda laws, maybe because they really believe the hateful messages.

As artists, our job is to find ways past this mask and these preconceptions. Athletes do this as well. They transport us to a place or a feat we could never reach ourselves. Artists and athletes create portals for people into other points of view, and dare us to see in new ways. I have yet to meet a single person who is truly apathetic. I have met many people, and been someone myself, who is unsafe or uninformed. So, it’s possible for Wilke’s The Jester’s Cap to be censored and seem ignored, and yet, through Wilke’s talent and the Center’s bravery, be recognized. Wilke’s voice has not been silenced.

But increasingly LGBT Russians are becoming silent. As violence against them becomes the norm, much of an LGBT person’s world in Russia is now underground. The online world is more important than ever, but it too is far from safe for LGBT Russians. The anti-propaganda law sparked an uptick in a trend that I’ve termed “date-baiting.” An unsuspecting victim thinks they’re finally meeting in person someone they’ve been corresponding with, romantically, online, but the date turns out to be a thief, an attacker or, in some cases, a murderer. Long online courtships are violently revealed as fiction in person, even in the broad daylight of a public park—as one of Tess’s interviewees testified. Oleg Mikhaillov’s play Pelmeny deals with this directly.

In Pelmeny, an older gay man meets a younger man online. He has the man over for a date and makes him pelmeny, a classic dumpling. As he cooks and tells the story of his life, he comes to realize that the man isn’t there for romance, but violence, and plans to murder him. It’s a requiem for those who risk living without a mask. This is what we ask of our artists and our athletes. To leave it all on the stage or the court or the track. To let us see the best and truest expressions of the human experience.

For how similar our jobs are, theatre artists and athletes don’t seem to talk much. We both train unwaveringly for performance day. We measure our successes by our own ability to push ourselves to new heights and depths, through new challenges. And, if we’re lucky enough to succeed, do we have a responsibility to use that platform to enable social justice and strengthen community? To use the amplification of our own voices to give voice to the silenced? To actively craft our own origin stories and narratives? This answer is different for each of us, but the question demands to be addressed continually over one’s career.

Propaganda seeks to spark dialogue. To examine Russia not just in this moment, but how it came to this moment. To examine ourselves in relation to Russia, and to give voice, on their terms, to the artists and athletes whose careers have elected them to the forefront of some of the most pressing humanitarian work facing our global community, as well as to the Russian artists and citizens whose voices are being silenced. Asylum is not good enough. There will always be young LGBT people without the option of asylum—how are they meant to live? In silence and shame until, if they are lucky, they are forced to leave their homes forever?

Nabokov said something else about sport. He wrote, somewhat prophetically, in 1925 that “the Germans too have lately realized that the goose step can only take you so far, and that boxing, football, and hockey are more valuable than military or any other exercises.” Sport, like theatre, is storytelling, and stories are power.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Please see below the link to reach the Russian text. It's available for download.

http://www.theatre-library....

and

http://termitnik.dp.ua/poem...

The English translation is not yet published.

Thanks for inquiring!

Where does one get a copy of Mikhailov's play?