Friday Phone Call # 46

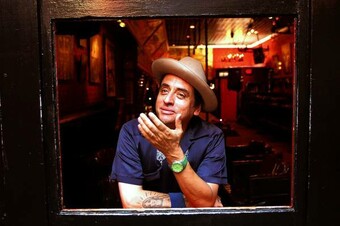

Noah Siegler, Artistic Director of StageNorth in Washburn, Wisconsin

Today my guest is Noah Siegler, who is the artistic director of StageNorth in Washburn, Wisconsin. There is such fresh air in this discussion—around the ways StageNorth connects with its neighbors, about the ways it organizes its business, about the purpose of doing it at all. I'm struck, in talking with him, about how close to community and purpose any organization like it is. For all the hand-wringing about impact and relevance that we see in the conversations here at HowlRound so regularly, here's a man who is in full relationship with his audience, his citizenship role, and his definitions of success. What can we learn from each other, what can we share with each other, that brings us closer to what Dudley Cocke started the week off with: "a theatre that's national in scope, regional in emphasis, and democratic in attitude"? Thanks for the time, Noah. Very glad to meet you.

Listen to weekly podcasts hosted by David Dower as he interviews theatre artists from around the country to highlight #newplay bright spots. You can subscribe to the series via iTunes or this RSS Feed (for Android phones).

Transcript in Progress

David Dower: Hello, Noah.

Noah Siegler: Hello, David. How are you?

David: I'm very well.

Noah: Good.

David: So, today I'm talking with the Executive Director of StageNorth, Noah Siegler. StageNorth is a theatre and bar on Lake Superior, in very northern Wisconsin. Yes?

Noah: Washburn, Wisconsin.

David: Washburn, Wisconsin. Excellent, and how long have you guys been in operation?

Noah: StageNorth has been in operation for eleven years. We started out in an old Lutheran church here in Washburn and after five years there, or six years at the old church, our owners decided that we had gained enough reputation and success that they built this all-purpose, gorgeous facility right on the lake. So, it overlooks the Apostle Islands and it's this gorgeous place and we've been here for five years now.

David: Five years in this new facility and if people haven't seen it, it's really beautiful. It's at StageNorth.com and just give our listeners a sense of the area. This is taking place as part of Rural Week on HowlRound. So, give us a sense of both the demographics in terms of the size of the community, and then also who's there.

Noah: Yeah. We are right in the heart of Washburn's theatre district as I always say. It's a town of two thousand people and we're right between Bayfield, which is the big tourist destination in Northern Wisconsin. Bayfield's fifteen miles north. Year round, that's a town of 600 people. And then Ashland is a town of 7,000, 8,000 people, which is ten miles south of here. So, it is a very rural community. Economically, sure we are boosted by the tourist trade during the summer, but for the rest of the year, it is a pretty economically depressed area, and it's tiny, and we are the one theatre in Northern Wisconsin.

David: What are the options that people have in the community other than the theatre for getting out at night in the off-season?

Noah: Yeah, there's a bar on every block so it is northern Wisconsin that way. People like to drink PBRs here in northern Wisconsin. So, there's bars, in the summer there's Big Top Chautauqua, it's a year round tent theatre, which just does music. So, it's a 1,000 seat venue and they bring in BB King and all kinds of nationally touring acts. The rest of the year, it's much more outdoor activity oriented, skiing, playing on the lake, that kind of thing.

David: And what's brought you to this job?

Noah: I'm from Ashland originally. So, I'm from Northern Wisconsin. I'm a young guy, I kind of fell into this job. I'm from Ashland. Went to school for theatre at Grinnell College in Iowa. Moved to New York for a few years. My wife was going to culinary school there. And then, people had heard when they opened up this new building of StageNorth, they knew that I was into theatre and that I loved this community. So, they called me to come back and take a look at it, and offered me a job. The former artistic director resigned right after this place was built. So then, I was here and I kind of flipped into this position. So, it's not like I had any ... I was twenty-five at the time, and all of a sudden saddled with this large building, this multimillion dollar facility, with no real background to it. At the old theatre, it was in this tiny church, where they only had to do only a few events a year. The revenue ... They didn't have to make a ton of money to make it roll. Here, all of a sudden, we need to make forty grand a month, which is a lot of money in February in Washburn, Wisconsin.

David: Because you're making it out of your own community. It's not like it's a tourist destination.

Noah: Exactly. So we just started there. What I didn't have in knowledge, what I didn't have in that base of ... You know, I've never run a theatre before. I just like to act, and direct. So, what I didn't have in that, I have in energy. And it's just like trying to hit the pavement and see what it takes to make a theatre go. And five years later, we're making it work. So, it's pretty crazy.

David: How is it do you think that the community has come to value live performance, theatre in particular, in your community?

Noah: Yeah. You know, especially when this place was just built, there is that stigma of theatre being upper crust, or intellectual, or that you need a degree to understand it. And then also coupled with the fact that our owners are from Minneapolis, and there was this kind of outsider feel. In a small town, that's a big deal, of like "Who are these outside, money people building this facility?"

David: Who did build it? Was it Summer supporters mostly?

Noah: Exactly. Yup. So John and Annie Winell, they built this place. So we had that first year of, we were fighting to make fifty dollars a night at the bar. So we started out in that first year, I just kind of started over again. And we did all these quirky, stupid, accessible things. The first decision I made was, let's start offering PBRs at two dollars, just so people, when they came into the bar, they knew that it doesn't have to be ten dollars a drink. It's just like any other bar. Then we started doing a facial hair competition, and cringe night, where people come in and read from their old adolescent diaries, and love letters. We did Big Lebowski festival. Just stupid things to get people in the door to realize that, okay, they can feel comfortable here, that it's not some foreign concept. And through those kind of activities, where people just coming in the door, realizing that they belong, then we could start doing concerts and movies and theatre.

So we started out kind of more with much more accessible theatre, we did the big musicals, but then through growing that operation, now we're doing the play a month. For the last two years we've been doing a play a month, and we can do the other things, too. We can do the Eric Bogosian talk radios, we can do the Brian Frail’s Dancing at Lughnasa, and we've developed enough of a relationship with the community that they support those plays as much as they support the Oklahoma's and Sound of Music's.

David: And what's the support in the community itself? How does the theatre fit as a citizen in the community? What's your relationship to the rest of your neighbors?

Noah: We are now kind of the anchor of this region. People are moving back to Ashland, Washburn, Bayfield, because they see this vibrant, cultural beacon of Northern Wisconsin. We're definitely an anchor here, and an economic driver, because all the hotels fill up, all the restaurants fill up before shows, but also we're that place where the community can come together, and in addition to seeing all these shows, we can also ... during the Scott Walker recall election, he came to Washburn, and there was an anti-Walker rally, and the Democratic Party rented out StageNorth, and closed down the street, and we had 3-5,000 people here for that. So they're using StageNorth as that community ... that central place, where you get together and have a drink, and talk to your neighbors, and see your neighbors onstage. We are now that place in Northern Wisconsin where everyone comes to hang out.

David: And you have a mix of trained theatre artists and community theatre artists who are making the work on the stage happen.

Noah: Yes. Yeah, it's a community theatre. We pay our designers who come in. We pull people from Minneapolis, from Chicago, in terms of directors, light designers, set designers, but basically, it's all community based artists. We're really lucky to have people who have done lights, who have done sets in the past professionally. So no, we're just a community theatre on steroids, kind of. There was a time last year where we had 115 people working on three different plays at once. One play was rehearsing in the basement, one in the attic, one onstage, we all meet in the bar afterwards. I mean, you have to pace yourself to remember that you're in Washburn, because it just feels like the energy in the room is just ... it's pretty amazing that a town of 2,000 people can support not only buying tickets to come see shows, but also to have 115 people working on shows at once. It's a strange phenomenon in a tiny town.

David: Noah, what for you personally is the relevance of much of what's discussed about American theatre to what you're doing? How do you connect, or do you connect to the rest of the energy of the field?

Noah: With what's happening across the country theatrically? Is that ...

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative].

Noah: It's a strange bubble here. We're always looking at plays that are happening all over the place, and we're always bringing in shows that are being performed in Minneapolis and Chicago-

David: And how are you doing that? How are you seeing that? Are you reading the newspapers? Are you getting into Chicago to see the work? How are you connecting directly in that way?

Noah: I'm getting in the car and driving down to Minneapolis and going and seeing fringe shows. I have friends through college that are performing in Chicago. And then just a lot through newspapers, online, reading what's going on. Because we only have 136 seats, we can't afford to bring in large touring shows at all, but we can afford to bring in a few actors at a time to work alongside our community actors, we can afford to bring in fringe shows, and we can see what other theatres are doing to see what's working and what's not working.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative]. And for the community of audience, I can imagine what's ... and I could be making this up. I actually am from a very small town. I grew up in very small towns, plural. Myself, and I graduated from high school in a town of 300 people, so ... I can imagine that most of what's going on between the art and the audience is actually related to its community itself, right? There's probably less of a sense of, "Oh, we're going to that theatre to plug into what is the world of theatre. We're going to the theatre here to plug into ourselves as neighbors, in a way."

Noah: Exactly, and I think that's right on, where you're going to see your friends and neighbors, your community. You're going to be proud of what this community has to offer. We're offering a space where it's just a playground for adults. It's like this place where people can come in, and maybe they've never been on a stage before, or maybe they've been in a few community theatre productions. But we offer this place where it's heart. We're not trying to just be community cheerleaders here. We are trying to create really immediate, wonderful art, and I think we do that for ... I will go to my grave thinking that half the plays that we do here, three quarters of the plays, can be done anywhere else in the country and not look like it's a small town based community theatre. I mean, there are -

David: But what does ... and I believe you, and I've seen that work myself in places, and does it matter? I mean, I guess it matters to you, personally, that you're making work that stands up on that level, right? But does it actually matter in terms of what you're doing there ... How does it matter, let me just say?

Noah: It matters in the fact that, where we got done with Hamlet last year, and the public library called me a couple days later and said, "All of Shakespeare's plays have been checked out. We're completely out of Shakespeare." It matters that there's an eighty-year-old farmer who comes in and watches Cyrano de Bergerac and comes up afterwards and is sobbing and saying he's never been to the theatre before and he's hooked. It matters in that way. But you're totally right on.

David: Wait, let's go back, because I think that is a perfect answer, and then we can go forward. What you just said was that, so you did your production, and then the library called you to say ...

Noah: That they were completely out of all of Shakespeare's texts.

David: Exactly. And that, right there, is two things for me. First of all that the audience responded in that way, but mainly for me, it's that the library thought to call you. You have a relationship with the library.

Noah: Exactly. They're right across the street!

David: Yeah.

Noah: I think you're right on, where it's just ... of course, from a personal level, I love the feeling of watching a play done at this community level with people who have never done this before, thinking and knowing to myself that this is really good stuff happening, and it's immediate, and it's ... We all go to Shakespeare in Minneapolis or Chicago, and we're looking at our watches wondering when we can leave, and knowing that, okay, we can do Shakespeare here, and it's not. There's something so immediate and so basic about having people who have never done this before, who are really smart people and want to do well. What I'm trying to say is, yeah, from a personal level, I love seeing that there's good art happening. I think my main pride of this place is that we are building communities through this theatre.

David: There's an intimacy to what you guys are doing. That is a challenge to get out of an urban theatre world.

Noah: Exactly.

David: We talk a lot in these conversations about trying to create community in theatre, and I think the challenges are so much bigger in a bigger theatre market to create actual community. You guys, you are community, so the intimacy with which you guys are all working, it's a very ... It's a much different thing to get onstage and perform in front of your neighbors, for your neighbors, than it is to be a kind of ... All I know is the biography in this program. I get a little hundred words about that person who's playing Hamlet on the stage. That's a very different thing than, "I knew that kid in high school, and I know his father worked for the law firm down the street." That level of intimacy is very present in what you're doing.

Noah: Everyone knows everybody up here. It is just such a close knit community. But I'd like to think, and I've heard hundreds of times that it wasn't as close knit five years ago. In part, it's becoming a much tighter community because of this gathering space of ... obviously, everyone knows each other's dirty laundry. Everyone knows everyone's parents and kids, and it is that small of a community, but it's one thing to peek at your neighbors through the window while they're yelling at their kids, and it's another to see those neighbors at the theatre, and see their kids in a production, and maybe talk to them for the first time afterwards. So it is this binding agent here in the community.

David: What's the impact of that intimacy on the range of things that you get to program?

Noah: The impact of the intimacy on the range?

David: Yeah, or that proximity, the presence of community in all levels of your work. What's the impact of that on what you program?

Noah: We can do exciting fun things. We're always trying to widen our impact. I still think of this as a nascent business. Like last year, we started doing this writer's workshop thing where we're pulling in, instead of people who are interested in theatre, we're pulling in people who are interested in writing short stories. So we pick a theme, the local newspaper organizes it. Picking the theme last year was food, and they got 110 people submitted essays on either a funny waiter story, or a story about past Thanksgiving experience, and we sold out a whole week of shows for them doing readings of their works. We can really just go off of what ... We just have an empty space, and we just try to fill it, you know? I know that sounds stupid. But we have 365 days to fill, and this community has so much to offer in terms of musicianship, and writing, and all facets of art that we just take every day and see how we can bring in another audience, or bring in another art form. Actually, we offered 207 nights of entertainment, and most of them sold really, really well. So for it to have the community here for 207 nights of the year.

David: How many total tickets do you sell in a year?

Noah: Around 15,000.

David: How many people live in your community?

Noah: 2,000.

David: Okay.

Noah: I wrote a letter to Joe Dowling at the Guthrie, because I saw at the Guthrie that he says that Minneapolis has the highest tickets per capita, so I wrote him a cease and desist letter, but he never wrote back, so I don't know why. We're doing tremendously well. It's a town of 2,000. It's crazy.

David: That's every single person buying seven plus tickets a year.

Noah: Exactly. It's awesome.

David: And some persons are still under two.

Noah: So they can't drink PBRs yet, but they will in nineteen years, so we'll get them.

David: What's your relationship to the education system there? Are you in the schools?

Noah: Yeah, grilling all the time. That's one of the most exciting parts of this. We're doing all kinds of stuff. So when we do shows like The Diary of Anne Frank, or Hamlet, or we tie it in, we go to all the different local school districts, tie it into their curriculum, make sure they're reading it. And then we bus kids in for special matinees. I go to all the local schools and talk about theatre, and acting. This upcoming year, we're doing our first artists in residence program, so bringing an actor in from Minneapolis who will be here for a month. He'll be performing the Much Ado About Nothing here, but during the day, he'll be going to the regional Native American reservations and the schools and giving lectures, and talks, and classes on theatre, and art, and then performing at night.

So we're always in the local schools. We just got done with a big all student production of Romeo and Juliet that was offered through the Washburn school district summer school program. And then every December, we do an all student production of Christmas Carol that we, after their first one, and I had a few different scripts, one with six people, one with sixteen, and seventy-two kids showed up. And we cast ... Our goal for the production was, by opening night, all the adults would take a big step away, and the entire theatre would be run by kids. Kids ushering, kids in spotlight operators, kids calling the sound and lights. We had a huge, multi-level revolving stage, and there wasn't an adult onstage ever. The whole theatre was run by kids, and it was a huge, huge success, and the most exciting thing that I've ever done, the most fulfilling thing I've ever done, to have kids be so proud of their work, and know that there were no adults anywhere near. I was standing there in the back ready to save the day, and I didn't have to at all. Kids ages nine to fifty-two were doing every facet of the production.

David: Who do you report to?

Noah: Nobody, really. That's what's really ... this is such a crazy thing. Our owners built the theatre, and then that's it. They live four and a half hours away. They come up every couple months. I talk to them, I talk to John once every couple weeks and let him know what's going on. But really the owners are so amazingly wonderful. It's like this gift for this community where they just built it, and said, "Here you go. Make it happen."

David: And do you guys operate with a 501c3, or are you operating as a for profit?

Noah: We're for profit. We're waiting on the IRS to start this not-for-profit educational wing to help us pay for the buses to get kids here, because schools don't have money. It's 500 dollars per bus to get them here for a show. So we'd like to underwrite that. So we're starting this not-for-profit educational outreach program, but no, as a theatre, we are a for profit theatre.

David: Mm-hmm [affirmative]. And I would imagine it's not a huge moneymaker, but that you're able to make it work without the benefit of a 501c3 structure.

Noah: We are. I mean, we're not there yet. When you have to write a property tax check for $22,000, again, it's a lot of money in April in Washburn. But we're getting closer and closer, and we're trending to ... We're in our fifth year, so yeah, we will be hopefully breaking even in the next year or two. So we're on our way.

David: So tell me, Noah, I have two sort of larger questions for you. One, and I think you've kind of hinted at it, but I want you to have a chance to be direct about it, how do you define success for the theatre?

Noah: That's a really good question. Especially those first couple years, it was really easy to get way bummed out when you see the profit/loss statement, and you realize that, we're trying to pay for this building, we're trying to pay for it, and you can only do so much. We're trying to keep tickets accessible for our area, sixteen dollar tickets or nine dollar tickets. So pretty quickly, I realized that success maybe was not going to come through the financial prowess of this facility. But the success, for me, is every time there's a new school bus that shows up for a show, or every time that ... when Christmas Carol got done last year, and you see that six-year-old actor at that final circle after the show crying, not because he was hungry or tired, but crying because he knew that he was a part of something bigger than himself, crying because he's going to miss it. These things that adult actors feel that you don't think that kids feel that way. We think they cry because they're tired. And knowing that they have learned something, and they can't wait for next year to do it again.

Every time, when I said the farmer came in and loved Cyrano de Bergerac and couldn't want to come back, those are the successes that I think this place ... the social capital of this place is astounding, and I think the good that we are doing for this area, sure, economically, but also just as a way to get to know each other, as a way to see each other at night, and not sit at home and watch Netflix or Modern Family, but to come here and watch something that your own community is doing. I think it's, at its best, it's a breathtaking experience. I love it.

David: Clearly. And then, I can imagine that you don't that often talk to the rest of your colleagues in the American Theatre, and there are lots of people who listen to this. What would you most like them to know? Here I am asking you all these things, but this is actually a moment for you, too. What is it that you would like people to know about the kind of work that you're doing, the why you're doing it, the how you're doing it, any of those areas?

Noah: I think StageNorth is so replicable. Sure, you might not have a philanthropic owner that's going to drop everything and build a theatre in your community, but as Scott Walters from Cradle Arts says, we're in this place in society where we're exporting all of our talents. We're exporting our actors, and our playwrights, and our designers to these big urban hubs, and I have friends in these hubs fighting to do plays for five people at night, fighting for that audience when there's so much around you, and trying to get even this small crowd to see your work. I think what we're doing here is just as exciting, just as immediate. This is fulfilling, and there's no reason why people shouldn't be starting these community theatres everywhere.

We all have this image of what community theatre is, and it usually is a negative. It usually is, oh, it's a community actors who you can't hear, let alone a good play. And I just think arts in America would be a far better place if we didn't all have to feel that urge to go to the big city all the time to fight for those two people when we're getting 15,000 people a year for plays. And that sense of community, that sense of fulfillment is just the same. And sure, we don't have The New York Times review here, but ...

David: What would that even mean to you?

Noah: I don't know. I mean, we've had people from Minneapolis, Chicago, all these people come up here, and their heads get turned. There's something, you can watch people get shifted a little bit when they walk in and they realize that, okay, it's just weird. Like, a town of 2,000 people shouldn't have a building like this, shouldn't have a stage like this, shouldn't have this kind of energy, shouldn't have three plays rehearsing at once, in the meantime having a new art opening, and a concert, and a lecture, and a film series, and a film festival, and ... you feel like this is some abhorrent thing, and I think that's totally wrong, that this is an abhorrent thing. Every town has community theatre, but I think it takes people buying into that. Buying into the sense of, community theatre offers so much to its patrons and to its participants, that I think often goes completely just up and forgotten about.

David: My first show that wasn't in high school, and I only started doing - I started, I was an actor. The first show I ever did was as a junior in high school, in a new school district. But the first thing the next year, I did a play at the little theatre, a community theatre in Jamestown, New York, and that was where I started. And I started, I learned all of these values that you're talking about, that they were just the kind of core values of ... The only reason, actually, I mean to talk about core values, is that's even to make it bigger than it is. The only reason to do any of it was because that's what was going on.

Noah: Exactly.

David: And then the spirit of that that most people come into it with, you guys seem to be maintaining that. I don't mean to be facetious about, what would it even mean to you? Clearly, it would mean something if the New York Times paid attention. I would mean something if the NEA paid attention. Clearly, I absolutely know that, and it would be a validation, and an important one. But on other levels, the real validation is coming from the library, it's coming from the school, it's coming from the grocery story.

Noah: Exactly.

David: And that's its own special set of masters that you serve.

Noah: Totally. I was very excited to talk to you today. It's not going to mean ... We're not going to sell a ticket, maybe, from this, and the review tribune doesn't -

David: I can guarantee you you won't.

Noah: Exactly. It's like when Scott Walters posts on his website about StageNorth, or even four hours away from here in Minneapolis, even when they do an article on StageNorth, it doesn't translate into box office sales for us. It doesn't translate into more success from this end -

David: But in other terms. Success as other people define it.

Noah: Exactly. I think you're so right on in terms of success being when you go to the schools, when you go to the library, when you go to the local bookstore, where people are talking about what you're doing and then wanting to read more, and wanting to see more, and wanting to be more engaged, and wanting to participate in this thing that they never knew that they even liked before. That's the success that we're dealing with here.

David: Well, it's very clear to me, and I love having the opportunity to sort of consider it as, how are we one big field, how is this all a continuum, and the lessons about this sort of ... I'm really struck by it, and I was struck by it thinking about this call, the effort to create community that so many theatres go through, and it's huge amounts of effort that so many theatres go through to just make any sort of authentic connection with the audience, and with the world that they're resident to, and what could be learned by simply looking at the world theatre movement, or the community theatre movement. Even in non-rural settings, where community is the wellspring, and community is the only ... it's the purpose, as well as the support system.

Noah: Exactly.

David: And what could we learn, what's transferrable, to some of these larger settings and institutions?

Noah: Yeah. And I don't know if anyone knows the answer to that, but I just know, at the ground level, it is just hugely, hugely exciting to be a part of a community that is so thirsty for anything. When we have our local costume designer talk about costumes of the 1890s, and we have a full house for people just hearing about costumes. When you have a community that wants to just drink anything up that you have to offer, you get goosebumps.

David: And it's totally doable. You said that, I hope you said it on the record, maybe we talked about it before we got on the record, but you didn't have any actual training for this in advance. It wasn't like there was some big program that you went through to learn how to do what it is that you're doing right now. You've been learning by doing.

Noah: Oh yeah. I was a twenty-five-year-old when I slipped into this position here. The first month and a half, I swear to God, I didn't do a thing other than go around and talk to as many businesses as I could, and talk to ... I was on the patio at StageNorth eight hours a day, and it was just kind of this open office where people would just stop by and like, "This is what I want to see here. This is what I want to see here." And just trying to figure out what ... we've got this building with no pulse to it. What is it going to take to have a life here? And working with all these local people, and working with all the local communities, and businesses, and artists, and just trying to figure out what the community wants.

This is not a very top down organization at all. If someone comes with an idea, if we have two people a year ago who say, "We want to do Animal Farm here with huge, Dewey Caymore puppets, can we do that?" And I pretty much say yes to everything, if we can find the money and if there's merit to it.

David: And then they have to know what to do with yes, once you've said that. Once you've said yes, it's up to them to figure out. They need to learn by doing, then, at that point, I would imagine.

Noah: Exactly. So now, five years down the road, we have all of these community trained directors, actors, light designers, grant writers, all these people who have done this. Our costumers here are like ... In the first year, we rented costumes from The Guthrie, and it cost a bunch of money, and then the week after the show closed, we had to send them back. Then we realized that we've got these amazing seamstresses here. So now, five years down the road, we're doing plays and not only are they creating costumes that are just as gorgeous as what we could rent from a big city, but they're doing the work. They're doing all this dramaturgical research to make sure that the costumes are completely right on, and this is a local eighty-year-old woman, who sits around her kitchen table at night at sews. These are all local people who just are buying into this thing, and buying into these methods of creating art, not for money. We're not paying. Going into making this community look good and feel good about itself, and understanding each other. It's crazy.

David: Well, thanks for spending the time, and thanks for all you're doing up there. I hope that there's some ripple effect of all of what is clearly great energy emanating out of the Northern Wisconsin there. I hope it emanates further into the field.

Noah: Yeah. That would be-

David: Good luck to you. I am looking forward to the news that you've turned it into ... you've reached the threshold of profit.

Noah: I think we're on our way, so that's pretty exciting.

David: I know that will be a big milestone.

Noah: It will be. Thank you so much for taking the time.

David: No, thank you.

Noah: Okay, talk to you soon. Bye bye.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Terrific conversation! Noah, I love the spirit of your "community theatre on steroids". While the economics of your operation are quite different from ours (Bloomsburg Theatre Ensemble, which is a full-time, year-round professional company, now in our 35th season in our small town), the stories are so similar. I would count your librarian calling you to say that all of Shakespeare had been checked out after your production of Hamlet to be a success of the highest order! Bravo.