The Long Shadow of Marble Busts

The Puppets

The hit Broadway musical Avenue Q stages a mock Sesame Street scenario as a venue to confront social issues with an acerbic twist. In one scene, a puppet named Princeton asks another puppet, Kate Monster, if she’s related to a Monster who lives upstairs. Her reply: “No! Not all Monsters are related. What are you trying to say, huh?,” sparks a musical number titled “Everyone’s A Little Bit Racist.” The history of humanity’s interracial tension distilled into jingle:

If we all could just admit

That we are racist a little bit

Even though we all know that it’s wrong

Maybe it would help us get along!

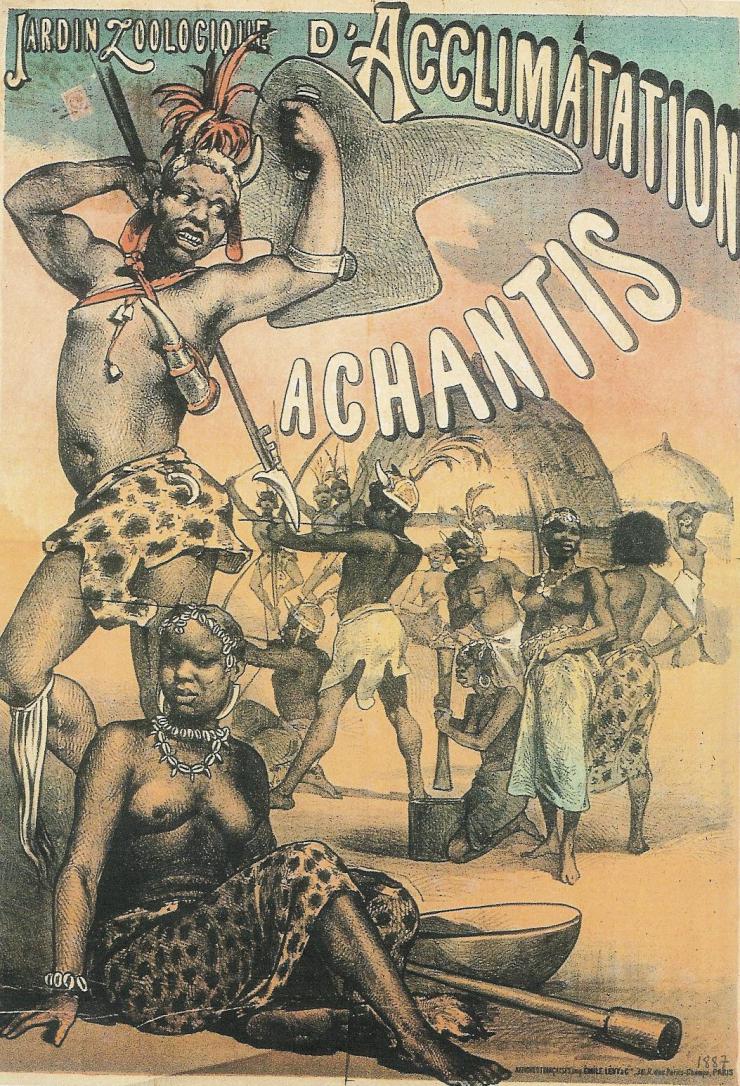

Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B proposes a different approach: a reversal of roles. In the space between theatre and art exhibition, Bailey poses actors in tableau vivants that nod to 19th century human zoos, and Southwest African concentration camps.[caption]

Thus far, white South African artist Bailey has staged the show in Brussels, Berlin, Avignon, Paris, Wroclaw, Strasbourg, Ghent, and Edinburgh.

The Controversy

In September, with Exhibit B scheduled to debut at the Barbican in London, Sara Myers, an African British mother from Birmingham, posts an online petition to shut down the show: “I want my children to grow up in a world where the barbaric things that happened to their ancestors are a thing of the past.” Following thousands of e-signatures and protests outside the venue, the Barbican cancels the show.

Bailey: I am critiquing Colonialism.

Protesters: This is racism sustained.

Journalists and bloggers weigh in. Alex Kessie of IndieWire: “If the purpose really is to educate about European Colonialism and racial subjugation prior to the 20th century, then it should and would be better to start putting it in our history books.”

Bailey’s cast issues a statement in support: “We find this piece to be a powerful tool in the fight against racism.”

Black Actor: Would I be right in assuming that you have not seen the work?

Black Protester: I have never, and will never, see a black and white minstrel show.

The Show

I see Exhibit B in Edinburgh in August 2014. An usher calls each of us individually, holding up a card with an assigned number. No one speaks. Everyone climbs the stairs to the exhibition hall silent, alone. Indigenous Africans stand among taxidermy wildebeests, birds, and monkeys. A choir of disembodied heads sing dirges in the languages of Nama, Otjiherero, Oshiwambo, Tswana, and Xhosa. Found Objects #1, #2, and #3: immigrants to Scotland seeking asylum from African nations “displayed” next to blown-up immigration paperwork. Names on a list enacted. Each a tableau, a frozen pose. Only eyes move.[caption]

Bailey says “the drama” of Exhibit B takes place between the “object” and spectator. Performance scholar Peggy Phelan would call this the relationship between the “looker” and the “given to be seen.” In her book Unmarked, Phalen provides examples of how various artists have transcended their position as the unvalued, the object of the gaze, the “unmarked.”

Unlike painting, photography, or film, which allow the spectator the luxury of a relaxed “gaze,” Bailey instructs his actors to follow each spectator with their eyes. Their “unmarked” gaze is unavoidable. Spectator caught in act of looking. Connection between eyes leading to a “humanity that defies objectification.”

I lock eyes with a young man with numbers on his chest behind a corrugated fence. Stripped of my power to implicate, I can only be implicated.

Is adding paragraphs to “our history books” really more effective than looking history in the eye?

Protesters: You are repeating the past.

Bailey: I change the past by giving it presence.

“The lure of the beautiful.” Each set, each actor’s pose, and each costume embodies cruelty impeccably composed.

I lock eyes with a young man with numbers on his chest behind a corrugated fence. Stripped of my power to implicate, I can only be implicated.

Exhibit B is playing at the Playfair Library Hall, Old College campus of the University of Edinburgh. Actors share the room with white marble busts of white male academics. On the staircases hang life-size portraits of white male academics—principals, professors, and chancellors.

This is a portrait of “Sir Edward Victor Appleton, GBE, KCB, MA, DSc, ScD, LLD, FRCSE, FRSE, FRS.” Check out that robe. By cohabitating this hall, Bailey’s living exhibit reframes these men as ghosts hiding behind distinction and paint, negligent relics of Colonial misdeeds. Bailey mocks the academics. Why can Appleton stay when Bailey has to leave?

By cohabitating this hall, Bailey’s living exhibit reframes these men as ghosts hiding behind distinction and paint, negligent relics of Colonial misdeeds.

Brothers on the Wall

In the film Do The Right Thing, an African-American man decides to boycott local establishment Sal’s Pizza because there are “no brothers” on Sal’s “Wall of Fame,” which features signed photos of Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio.

Spike Lee’s character, Mookie, functions as the film’s moral compass. He tells his friend to calm down, it’s Sal’s restaurant, and he can do what he wants with the walls. Mookie lets scene after scene of casual racism slide, but when Sal calls one character a “n*****” and bashes his boom box with a bat, inciting a brawl, which escalates to white cops killing a black resident, Mookie, the pacifist, throws a trashcan through Sal’s window. It’s the right thing to do.

Bailey: I put “brothers” on the wall.

Protesters: A wall of victims.

I attend a Q&A in the Playfair lobby shortly after Exhibit B closes for the night. A few of the actors walk down the stairs in their street clothes. They wave goodnight to Bailey, the master puppeteer. He waves, “Cheers!” They’re co-workers, not puppets. Or are they? Is ventriloquism the underlying issue here? Is Bailey’s show just a way of working through his own guilt, an attempt to rectify the behavior of his ancestors?

Protestors: You’re not black.

Bailey: But I have a lot of black friends.

A month before seeing Exhibit B, at Kara Walker’s A Subtlety at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, I watch an African-American man and his son, about four-years-old, crouch next to a sculpture of a slave boy carrying fruit. The sculpture, made of molasses, melts in the July heat. The boy drips, coagulates, shades of corroding brown. One shoulder has fallen off, so he stands in a puddle of his own remains, his own wet skin. Adult spectators respectfully avoid the puddles, but the four-year-old boy dances in them, sugar sticking to his sneakers. He doesn’t “see himself” in the molasses boy, but maybe his father does, or I’m projecting that interpretation onto him, and he calls his son, puts his arms around him, and none of us know what the others are thinking as we watch a boy melt before our eyes.

Kara Walker says her work also calls attention to gaze:

How do people look? How are people supposed to look? Are white audiences looking at it in the right way? Are black audiences looking to see this piece? And, of course, my question is: What is the right way to look at a piece that is full of ambiguities and ego?

At that moment, was my gaze “right?”

Shades

“Black British” Sara Myers

“White South-African” Brett Bailey

“Black British” Alex Kessie

“African-American” Mookie

“Italian American” Sal

“Black American” Kara Walker

“White American” Peggy Phelan

“White American” Patrick Gaughan

“White Scott” Sir Edward Victor Appleton

“Puppet” Princeton

“Puppet” Kate Monster

The Subtleties

Outside Exhibit B, in the Old College courtyard, I’m no longer silent and alone. I return to my community. One friend of mine was close to sobbing until an actor winked at her, wearing an “I’m a Muslim / Don’t Panic” t-shirt. Another friend did break down, and was greeted by a smiling African woman in the lobby, who wrapped an arm around her. At the Q&A, Bailey tells us this woman took the role of post-exhibit greeter after she was too overcome by emotion to act in the exhibit. She wept at every rehearsal.

At the Q&A, Bailey tells us this woman took the role of post-exhibit greeter after she was too overcome by emotion to act in the exhibit. She wept at every rehearsal.

It seems worth noting: these two friends and I were (are) middle class white Americans in our early thirties pursuing, or recently completing graduate degrees. We received funding from a large state institution to attend the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and Edinburgh International Festival. The institution paid my 15-euro admission to Exhibit B.

Writing inevitably exposes ignorance. It could also be a way to learn, a mode of listening.

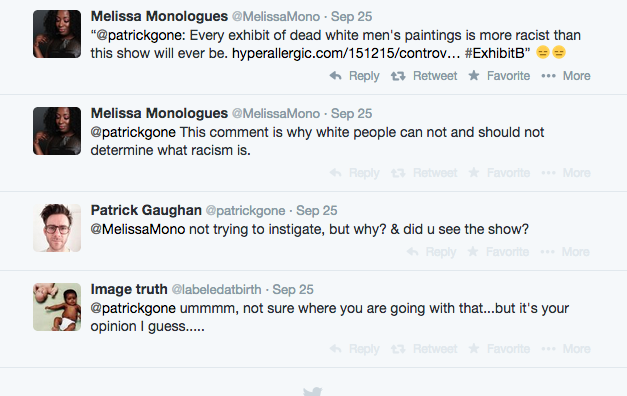

So it follows that when I read about the Barbican cancellation, I do what one does when one feels strongly enough to speak, but not take action: I tweet. “Every exhibit of dead white men’s paintings is more racist than this show will ever be. (Link) #ExhibitB.” A stranger retweets me, my words framed as a textbook example of white ignorance.

My "did u see the show?" not intending to lead to a "no? then u can't have an opinion about it,” not trying to gaslight anyone but retroactively seeing an ignorance, a privilege on display.

I tweet: 'Every exhibit of dead white men’s paintings is more racist than this show will ever be. (Link) #ExhibitB.' A stranger retweets me, my words framed as a textbook example of white ignorance.

It’s very possible I don’t know what I’m talking about.

If we’re all a little bit racist, where is that racism?

Protesters: In the bone.

Bailey: Maybe only in the eyes.

Protesters: Maybe only in interpretation.

I am not trying to “determine” anything. Whatever the opposite of “determining” is, that’s what I’m trying to do. No matter my intention, I’m ventriloquizing. Staging a puppet show.

The Leaky Valve

In her book Performing Remains, Rebecca Schneider says: “The present and the past were both possessed of leaky valves, the drip fed both ways.”

Bailey: Protesting the show is like calling the town’s worst plumber. In a month, the faucet will drip again.

Protesters: Is your intellectual crusade to look the “right” look?

Bailey: Look the past in the eye.

Protesters: We’ve looked so long we are tired of looking.

Bailey: But this error. This blatant mistreatment.

Protesters: Mistreatment couched as heroism. A history of mistakes.

Bailey: I understand. I’m trying to understand.

Protesters: You don’t see.

Bailey: This is a way to stop the bleeding.

Protesters: That’s not your blood.

Bailey: What about “community?”

Protesters: What “community?”

Bailey: So I should keep to myself?

Protesters: You’re not a hero.

Bailey: I’m not those men. I’m trying. See the show. Refusing to have Exhibit B demystified, refusing to make it a real event, will damn it to the imaginary. The evil conjured by one’s imagination is infinitely more hateful than any actual experience. I’m not saying I’m right. I’m trying to talk, the closest thing we have to a prayer.

Schneider notes that George Santayana’s 1905 aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” is “one of the most often misquoted ‘remarks’ of all time.” Or one could say it has many possible interpretations.

Those who do not read history are doomed to repeat it.

Those who do not remember their past are condemned to repeat mistakes.

Those who restate the past repeat it, in a way, but never repeat it exactly.

Those who forget the past are doomed.

Forget most of the past. Only remember the good stuff.

Of those who remember the past, only certain people should repeat it.

Is history written by the winners or by those who never “saw the show?”

Those condemned to repeat the past may not know how it originally went.

The act of forgetting that one is condemned could be very liberating.

Those who are condemned may forget they are condemned so you many need to remind them.

Those who cannot remember the past and those who can remember the past both try to repeat it. They take lots of photos and video and study it very diligently. They pull all-nighters and practice very hard over a number of weeks. The time comes for them to repeat the past. They fail.

Those who forget the past live in the present. Which might be better.

Those who condemn the past are probably right.

The past is not the past until it stops being repeated.

The molasses boy is always melting.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

The protesters remind me of those who protested Mapplethorpe in the 90s. They also, "didn't see the show." It is ridiculous to protest an artist based on hearsay. But some people see oppression everywhere, even in their friends.

One way to stop racism is by education. Looking at the root of the problem will help clear the way for a solution. It's not that we are tired of seeing history over and over again, is the fact that history is still alive and some of us don't know why!

completely agree with you, Rania / & that education is a long, hard road

Just wanted to say this essay was a great read. Difficult topic, engaging style and structure.

As an ethnic minority, I'm still mulling this one over, but would have wanted to see this show at the Barbican (I'm London-based) and make up my own mind. It's sad people like me never got the chance.

thx German! / I'm still mulling it over too