The New Theatre Season in Germany

Occupation and Immersion

The new theatre season in Germany, especially in Berlin, has started with a lot of highlights. But the big news was that a group of about 100 German theatre activists called Staub zu Glitzer (Dust to Glitter) squatted in the Berlin Volksbühne between 22-26 September 2017.

'We take possession of the theatre and declare it the property of all people.'—Staub zu Glitzer

This was an until now unknown form of protest against the change of a theatre director, since directors are more or less public positions. As I discussed in The Post-Dramatic Turn in German Theatre, the issue was that the majority of theatregoers did not want the former Director Frank Castorf to go (even after twenty-five years!). Castorf made the Berlin Volksbühne the strongest theatre with the most interesting and intelligent productions, which included his own Dostoyevsky Cycle of four masterpieces between 1999 and 2016, and the installment of René Pollesch as the director of the Prater-Stage of Volksbühne Berlin, the development of the famous Prater Trilogy, and the installments of Christopf Schlingensief (d. 2010), Christoph Marthaler, and Herbert Fritsch, as house directors.

Since the German theatre system, unfortunately, is built on regular changes of their directors (Intendanten-Wechsel), usually after five years, and members of the ensemble, after two to five years—this act of protest was unexpected. Especially, since Castorf was the only theatre director with more than twenty years at the helm of the most important German theatre.

On 22 September 2017, Staub zu Glitzer invited media to a press conference via Twitter:

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,

It happened. The VB61-12 [title refers to a nuclear bomb] was placed and she ticks. In a huge transmediale theatre production, hundreds of people have just entered the building of the Volksbühne at Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz. On the spot, they create something that has happened never before.

In addition to hosting a press conference, Staub zu Glitzer planned various art actions, panel discussions, readings, and a “parliament of the homeless.” They asked the technicians and workers of the theatre workshop to come, but none did. And they asked all former Volksbühne directors to integrate their repertoire pieces into the future schedule as far as possible. But none of these persons came either. The protest, which began as a very democratic movement, lost its momentum.

The group explained that “a core of about forty people with a cloak of up to 110 people” had been actively involved in this operation for more than half a year of preparation. The collective designates itself as “feminist, anti-racist, and queer.”

“We take possession of the theatre and declare it the property of all people.”

Eventually the activists gave in after the new theatre director Chris Dercon (and former director of the Tate Modern in London) asked the police to take over the house peacefully, without drawing weapons on the protesters or arresting anybody who participated in the squatting.

The theatre-activists, however, treated Dercon and his team in a very hostile manner, overlooking that that the Berlin senate was the responsible institution, which had elevated him and fired former director Frank Castorf.

Confronted by the new situation of squatters in the theatre, Dercon’s team only wanted to concentrate on their program and on new productions. Protestors treated them like enemies and intruders in their own theatre house.

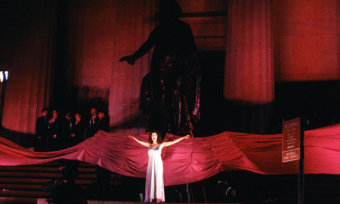

Nevertheless, the first artistic projects of the new Volksbühne took place. The theatre’s new season launched with a twelve-hour dance event on 10 September by choreographer Boris Charmatz on the old airport field on Berlin Tempelhof, connecting his professional dancers with the public. Everybody who wanted to dance with the professional dancers could do so. They counted nearly 1,000 dancers on the field. Imagine 1,000 dancers in the Central Park or in any other American public area! In Germany, this theatre approach is called immersion. The people, the public, the theatregoers are invited to come to the stage, or to be the stage, to come nearer to what happens on the stage and/or to become part of the scene.

Immersive Theatre in Germany

Immersive theatre has a long history on some stages. Its origin varies, although one starting point comes from psychological training, where immersion therapy is a technique, which allows a patient to overcome fears via confrontation by interacting with the object of their fears.

In virtual reality, it is a perception of being physically present in a completely nonphysical world. But immersion is as well the state of consciousness where a "visitor" or "immersant’s” awareness of physical self is transformed by being surrounded in an artificial environment, which, for example, could be transposed into the performing arts.

Immersive theatre projects do not change our perception of what we see, but they can change what we feel or sense. The line between the physical self of a visitor and her digital alter ego is flexible.

Participants may have opportunities to overcome both their own borders and the limits of their knowledge and their sensitivity and feelings. The diver is the best role model for the visitor in immersive theatre. They go into new environments, especially in the arts and theatre, where they can dive into performative situations or into whole performances.

Visitors should learn to use their complete range of knowledge and competencies like perplexity, suspicion, astonishment, lust, anger, and disgust to lead them to their own limits of personal and artistic and philosophical questions. It is a way to build bridges and to close gaps between the performing arts and gamers and developers of new virtual realities, as well as to philosophers and media artists, to merge parts of the performing arts with completely new influences.

Immersive theatre projects do not change our perception of what we see, but they can change what we feel or sense.

In the German theatre community many people look at these developments very suspiciously, because they fear to lose touch with the part of culture they have been working and fighting for for several years—which is the German theatre culture, born in 1800 and being the reason why Germans have the highest density of public funded theatres in the world.

Rimini Protokoll

Rimini Protokoll, one of the most interesting German theatre companies have been working on a new immersive theatre project which was shown in Berlin in July. Estate accompanies eight people who for different reasons prepare their farewells, using the time that is left to them to explain what will remain when they are no longer there. A base jumper completes a risk insurance policy so that in the event of his death his family won’t suffer a financial disaster. A German banker thinks about his position in national socialism at the end of his life. An EU ambassador documents her foundation that will continue her work in Africa after her death. A Zurich Muslim organizes the return of his corpse to his hometown of Istanbul. A dementia researcher will realize that he does not want to live with the disease he has been researching for a lifetime. And a ninety-year-old employee wonders what photos of her life will tell those she leaves behind.

The audience enters eight immersive spaces, kind of like mausoleums of the twenty-first century: eight contemporary positions on what heritage can mean today. What do we want to pass on to the people we love, and to the society in which we live? The audience is immersed in eight immersive space installations and are guided by voices, objects, and images to the limitations of our own existence.

As we look ahead at German theatre, I am sure that both developments can stay and play together—the performance aspect, which we see as the traditional one (even if they are today the avant-garde)—and the immersive projects. As German theatre looks toward the future, it may find a lot of new collaborators in industries that can finance parts of our research, training and production of new plays of this kind. Or is this too dangerous, to become more and more dependent on the funds of these industries? It would be a new register of German theatre, which is usually funded to 80 percent by public funds of the cities and federal countries (Bundesländer) Article 5 of the German Constitution (Grundgesetz), guarantees the freedom of Culture and Arts, Science and Teaching. This must be the cornerstone of whatever happens next in German Theatre.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here