Tilikum and Wading into Better Criticism

Theatre is for everyone, and all art is political. As theatre artists and practitioners, we tout these assertions as a means of demonstrating inclusion and value to society. Yet one of the most visible, value-asserting practices seems to be lagging behind: criticism. If theatre is a mirror by which to view the world, shouldn’t we bring the world and context into reviews? Art comments upon society and the human condition, it takes us from our personal reality and sits us down in front of another. But it is not a total escape from what we know to be true. A critic’s job is an urgent one. So what does it look like when they get it right?

Let me back up.

There are sirens, loud and undeterred. The red lights follow, flashing. But we’re underwater and the soft blue waves are in no hurry, rolling and rippling along. Tilikum the orca (embodied by Greg Geffrard) swims through in a wide-eyed panic, challenging the current, but ultimately succumbs to the basket in the sky, a fisherman’s net. Tilikum, constrained as the net tightens around his body, neck to ankles ensnared, resists, but soon falls unconscious and goes limp. Lights.

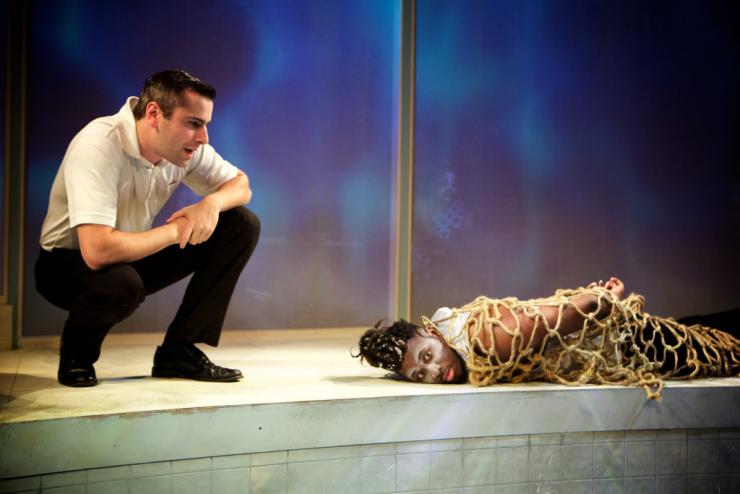

We’re back and Tilikum is still wrapped in the net, with the Owner (Matt Fletcher) towering over him. The Owner, aptly unnamed, is the face of capitalism, brutality, and sexism packaged into a neat, suit-wearing businessman. He taunts the killer whale and monologues about profit: “It’s not fair how much money we’re about to make.” Tilikum does not understand the small man’s tongue and he struggles against the knotted ropes. The Owner yanks the net like a tablecloth magic trick and Tilikum tumbles into a tank.

Soon, Tilikum realizes he’s not alone. Three orcas, goddesses, share the space with him, but they speak in a different tongue. He swims the length of the tank. He gnaws the bars; he shoulders the walls.

This magic can’t hold us

This magic is small

Small man with small magic

I can’t breathe

Tilikum exhausts himself and lets the water cradle him. The goddesses watch, knowingly, apathetically. He rocks to the bottom of the tank.

A critic’s job is an urgent one. So what does it look like when they get it right?

When he awakes, the goddesses tower over him. They introduce themselves, enunciating their names through drum beats (struck onstage by performers Joyce Liza Rada Lindsey, Melissa F. DuPrey, and Coco Elysses); a beautiful sequence of sound sharing and discovery.

“Tilikum” means all of us

But now, it’s just me

In fact, the only unnamed character is the white man, the Owner. (Refreshing, right?) Alas, Tilikum is stuck in a crowded, small tank, and his only opportunity to stretch out and feign freedom is during daily SeaWorld performances.

Wouldn’t be so bad if we got more frozen fish

Wouldn’t be so bad if we had more space

Wouldn’t be so bad if I could see my mama

To the uncritical, potentially ignorant eye, Kristiana Rae Colón’s new play Tilikum is an animal rights activist piece based on the true events of a killer whale caged in quarters too small, living as a captive for the entertainment of paying customers. Produced by Sideshow Theatre Company in Chicago, with a July 2018 world premiere at Victory Gardens, this play easily could have been a docudrama on the controversial orca—controversial because of his treatment as well as his killings. In fact, Tilikum’s story is central to the 2013 documentary film, Blackfish, which exposed SeaWorld as a literal breeding ground of captive whales as far back as the 1990s. By 2010, Tilikum had killed three of his trainers, including Dawn Brancheau (Sigrid Sutter), who is depicted in Colón’s piece.

In her playwright’s note, Colón proclaims, “Spoiler alert: this is an abolitionist play. That means it is in my canon of work that asks you to imagine a world without prisons and police.”

But let’s assume you didn’t read the note. How long would it take you to see the metaphor?

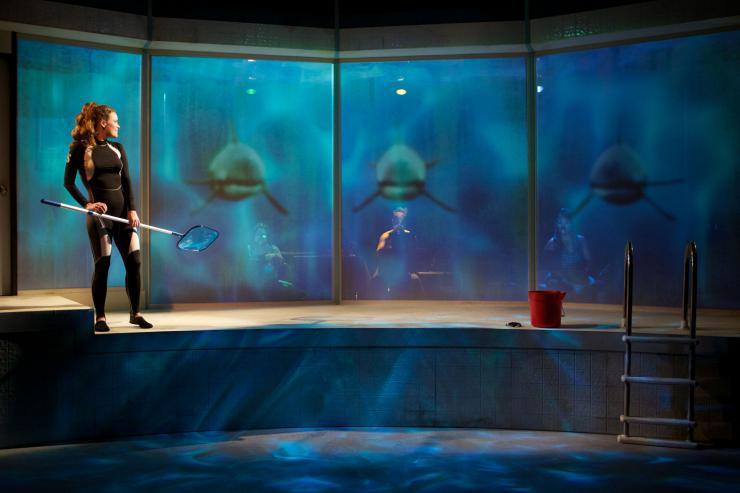

Colón’s piece is a gorgeous tribute to the black and brown bodies still stuck in limbo, incarcerated and separated from what makes them most human. But it is not all tragedy. Moments of reprieve come in the form of dancing, as well as connections between Tilikum and his trainer, Dawn. Rebuilding a world without cages is closer to reality than we may sometimes think. Lili-Anne Brown’s staging is masterful, with a set horizontally spilt three ways: at audience level there is the pool, above it the observation deck, and then a raised platform behind a “glass” tank wall. Though much of the action was immersed in water and subtle shadow—thanks to beautiful projections by Paul Deziel and lights by Jared Gooding—we were never too far removed from the very real subject at hand: prisons and policing.

Whale-on-whale violence

The more decisions you have, the more you are controlled

Another cage another collar—dollar

Often, when critiquing the work of artists of color, white critics trip over their racism (unconscious or not) and later fail to acknowledge their harms. Like microaggressions—someone asking, “Where are you really from?” or complementing a POC for “sounding educated”—such reviews have the power to compound and affect artists of color long after a show closes, from loss of ticket sales, to loss of future jobs, to loss of morale. So, we call for change. We call for voices of color to cover our shows and stamp a review into history so it’s not left to institutions and the inevitable supremacy of white minds. We call for white critics to be brave in their coverage and acknowledge realties different from their personal experiences.

We are beyond having reviews that are summaries and opinions on aesthetics. We need context and attention to detail in criticism.

Black and brown folks continue to be harassed for living their everyday lives, something that can be seen in situations like #PermitPatty and #BBQBecky and #IDAdam. These instances can easily end in a traumatic, uncalled for arrest. A critic must be culturally and socially aware of our world so that when they witness a production with a locked-up and beaten-down whale, desperate for freedom and mourning his lost future (wife and family included), they can see it as a metaphor for the hundreds of thousands of black and brown bodies locked away in our prison system.

We are beyond having reviews that are summaries and opinions on aesthetics. We need context and attention to detail in criticism. And we must not turn a blind eye to a playwright’s activism. In her own life, Colón goes beyond the text of her poems and plays, working on the ground to incite change. Cofounding the #LetUsBreathe Collective, shutting down traffic to block the International Assembly of Chiefs of Police—this matters. Tilikum is not just entertainment. It’s a call to action.

In Colón’s note, she writes:

Spoiler alert: this is an abolitionist play. That means it is in my canon of work that asks you to imagine a world without prisons and police. Another spoiler: slavery was never abolished. The 13th amendment made forced bondage illegal except as punishment for a crime, in a nation that has waged a centuries-long campaign to villainize and criminalize Black and brown people. Spoiler: that means every day you have drawn breath in America, slavery has been legal, in the form of prisons.

Tilikum is not only about a whale, and SeaWorld is not our true oppressor. This production does not demand special knowledge to be understood. Herein lies a critic’s responsibility to enter with an open heart and mind and to acknowledge when and where the play is written. Only with such a willingness to engage and explore will reviews do justice to the labor of love and urgency that appears before them. And only then will ethical and full reviews be stamped into our history.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here