After the Big Top: Carlos Alexis Cruz on the Evolution of Modern Circus

Theatre History Podcast #63

The classic circus, featuring performing animals in three rings under the big top, has passed away. What’s taken its place? That’s the question that CarlosAlexis Cruz is exploring with his studies in the rise of acrobatics and the modern circus. He joins us for this episode to explain how the circus has increasingly become a place where performers use their bodies to tell stories and invite the audience to join with them in celebrating the amazing physical potential of the human form.

Links:

- Learn about CarlosAlexis’s work with Pelù Theatre and The Nouveau Sud Project.

- Visit Circus Now’s website to learn more about the world of contemporary circus.

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

Transcription:

Michael Lueger: Hi, and welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. What does it mean to go to the circus nowadays? The days of the big top and performing animals are gone, but what's taken their place? And how and why did these changes occur? These are some of the questions that professor CarlosAlexis Cruz is exploring in his work. Carlos teaches in the Department of Theatre at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. He's the founder of Pelú Theatre and the Producing Artistic Director of the Nuvo Suit Project. Carlos, thank you so much for joining us.

CarlosAlexis Cruz: Thank you.

Michael: Can you give us a brief outline of the history of circuses in North America? What did they look like? and what sort of acts did they feature?

Carlos: Very, very interesting question because I think the history goes as long as tales as well and what people recollect from that. I'm researching indigenous acrobatics, which precedes what we already know from the formal circus arts. I think we will find in there, not only the roots of certain acrobatic moves we use nowadays, but also the meaning behind them—which I think we will discuss later about contemporary circus overall.

I'm very interested in the ritual aspect of it, and being able to illuminate why we use certain moves and certain aspects of it, and what we can accomplish with them. We know that acrobatic has existed probably since human kind, and I wonder and ask my troupe members, "Who was that first human that did a backflip?" I think in the 1800s, we have the first person who did a backflip on top of a horse. I mean that's been documented, but who was it? That would be really hard to trace. I think before anything we need to understand why we call it circus.

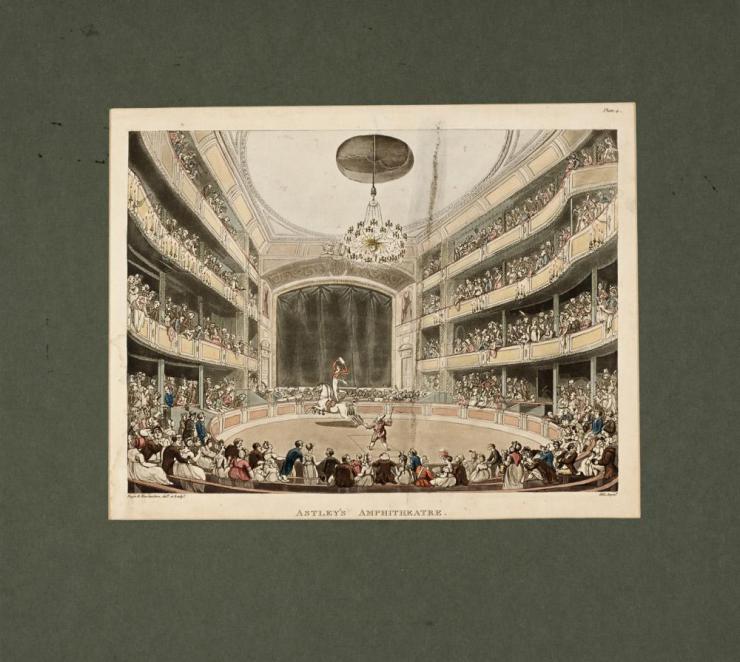

The first thing people need to know is that this type of performance originated from horse-vaulting and horse-riding. They used a forty-two feet radius circle—we call it "pista" in Spanish—so the horse can run multiple times and we can see more skills happening without the horse going back and forth. The audience would have a hard time seeing that instead of seeing the circular action. This was in 1770 in England.

From there, and going back a little bit, this guy named Phillip Astley was an equestrian, a military equestrian individual, who formed a school on how to mount and ride horses. From this school, they created these shows at the end of the day. After two years, those shows probably became more popular than the classes themselves. Then they had to diversify what they were offering, therefore they brought different tastes to it. So they added comedic elements to the horses, started doing a little more acrobatics, borrowing from elements that are preceding all this and that have been seen before: jugglers and what we call fulambilistas which are like people walking on the tightrope and so on. We call that the birth of modern circus and what we call circus today. We call that modern, and then we call something else contemporary.

From there, there was a competitor to Phillip Astley. His name was Charles Hughes and one of his pupils, John Ricketts decided to move to the United States and start the same thing, an equestrian school in Philadelphia. From there, a similar aspect happened—they started doing shows and by 1793, in April, we call that the first official circus performance. Still, that circus performance was done in these old venues. They had the roof missing, and the main thing, I guess the piste or the ring. So that's the beginning of circus.

These shows became more popular, and drama would happen, and buildings burned, and new railroads happened, and there was a constant push in this country to go West. That kind of triggered the development of a moving circus, a show that was not just in one place, in Philadelphia where it was created. It went to New York after that, or Charleston, South Carolina. Now it was reaching where people were at. The invention and the use of the actual big top followed that as well. So if you take into consideration the railroad going West and the big top and having key figures such as P.T Barnum joining the initiative more out of business than anything else created what is known as the golden age of circus in the United States which we see was really the mix of this equestrian act. They also had to maximize that because there were audiences that could not fit inside the venue, so they started creating multi-ring circuses.

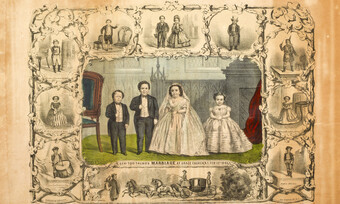

So you can see maps with different structures of three rings, different platforms so there was a multitude of action going on. Even by the latest shows of the Barnum and Bailey Circus you see elements of that, we call that a three-ring circus because so much is going on and it's a little hard to pay attention to what's happening and yet everything is spectacular. I think that the P.T Barnum figure is pretty key because he also brought the idea of side shows and acts and other performances. Also, it became like a traveling zoo of sorts. There were these exotic animals traveling between places.

One of my favorite stories is in 1882, Barnum bought a big elephant—a giant elephant from Africa called Jumbo—and Jumbo died unfortunately three years later in a train wreck, but I find the story fascinating because we sometimes don't know where names come, from or why we call things certain names. We call things Jumbo, like big things, in the United States, but the name comes from this gigantic elephant. I think that show, that became the original circus, that later became The Greatest Show on Earth, that had like a golden time between the '20s and '30s in the United States, and unfortunately for situations in life, we see the closing, Barnum and Bailey lasted 146 years. It was primarily rooted in the fact of the spectacular, of reaching the audience and providing a variety, a space for everyone. In that space, you will see the impossible take place. So that brings a little bit of the history of the circus in this country.

Michael: So, in addition to the more conventional history of the circus, you've been looking into things like the history of indigenous acrobatics. Could you tell us a little bit more about that side of circuses and specifically acrobatics?

Carlos: Yes, I went on a recent research trip to Mexico. I encountered that several local tribes of indigenous groups have been trying to preserve their own heritage. I've been very familiar with the Voladores de Papanda which they spin around this big pole. Then I encountered several actions that are similar to tightwire or clown swings nowadays which they call columpio. Why I'm intrigued about it is because they were not necessarily done for the fact of entertaining but they were performed for the fact of a spiritual relationship between their spiritual lives and the connection to the community. This sort of communal, spiritual action intrigues me. I think it happens in the circus and it happens in performance when we see something together, but the use of acrobatics and defying death to a certain extent to do that is quite intriguing to me. I think the meaning has to be way deeper than what I'm just describing right now, and I think it can shed some light on how we can continue to use acrobatics today for the purpose of telling stories, for the purpose of continuing to develop this communal sense within a group and an audience that is witnessing the event at the same time.

Michael: It's interesting that you talk about telling a story through acrobatics, because it sounds like that's where contemporary circus has gone over the last couple of decades. Could you tell us a little bit more about the recent history of the circus? How we've gone from the classic story that you just told us about to more recent performances?

Carlos: Yes, and precisely that's probably how I came to the circus as well. I came to the circus from a theatrical mindset and I came to the circus understanding more contemporary circus than anything else. There's been perhaps a level of attachment between the two sides and for me that's very fascinating, but I think we can trace back what we call contemporary circus to the '70s in France. This genre grew out of rebellion, changing the art. They went from the traditional use of animals to exploring the human body, more in a research of what the human body can do. What does that mean when you put a certain body doing certain moves? That started nouveau cirque, which means new circus in French. That started a whole movement that translated to several schools in France.

There is a key name, Giles Ste-Croix. Giles Ste-Croix studied circus in Europe, and from there he went back to Montreal and founded his own circus school. At the same time, there was another guy named Guy Laliberte. He was a street performer and he created a street festival for street performers. The two get together in ways that we can cover in a deeper conversation, but basically, Giles Ste-Croix and Guy Laliberte form what we know today as Cirque du Soleil. Cirque du Soleil's first season in Canada was in 1994. So from the '70s to the late '70s, early '80s when Giles Ste-Croix went to Europe and came back, the foundation of this was really good time.

Also, I think it's good to say that they were able to say this because of the funding from the government to support the Francophone culture. It all makes sense. This is something that is coming from France, it's a new art form, a new way of seeing a culture that represents part of France. To have that be the way of preserving the culture, I think it's a genius move. They continue to explore this modern way of looking at the circus. I don't wanna say it's not as spectacular, it's just not based in many aspects but the human body. I think, in essence, if we talk about nowadays, obviously skipping the development of what Cirque du Soleil did, how Cirque du Soleil got to the United States, how Cirque du Soleil now has Vegas which became a key component to what Cirque Du Soleil is and their economy. Why Vegas, and the spectacular need with the timing of the shows, and so on.

If we skip all that ahead, in essence, what Cirque du Soleil started to do, although they developed a brand, but if we see contemporary circus today, all that we are trying to answer is: We see a human with a special talent, a human that can do things that no one can do and you see them accomplish despite these tangible, physical obstacles, we all rejoice. The obstacles in the circus are not necessarily like in theatre where they pretend obstacles, we're playing, we're doing a play. In the circus, doing a flip, or lifting yourself, or flying over the audience, the action is literally happening. If we see that action can be accomplished, we either celebrate or suffer, we are moved by those actions. So I think in direct answer to that, and understanding the power of the individual as an animal of sorts and how we accomplish things is at the heart of everything that is the contemporary circus.

Michael: We don't think of circus performances as telling stories, but you've spoken with some artists who are doing just that. How have these changes led to new narrative and artistic possibilities for circuses?

Carlos: It's a good question because it goes for a deep answer. I think Cirque Du Soleil opened a door for us to see circus from a different angle, to separate from the nostalgia of the golden era, or from the pushback that people had to that era because of the animals and what not, but the circus can be done without that. If you see a Cirque Du Soleil show, you're not seeing the performers, you see colors, etc. Especially the first shows, they were like alienesque figures. They were not human characters if you understand what I'm saying. That in itself was very appealing as a large scale image, but not truly connecting human to human, and I think, as I said if you go back to the root of what contemporary circus is, or the acrobatics, even indigenous acrobatics, we see the human actually doing the tricks, then the contemporary circus is almost a pushback to what Cirque Du Soleil has done which is taking all the makeup, taking all the fancy costumes out, and just having a group of artists come together to tell their stories.

I think, in essence, that the circus really validates or empowers the individual because we also say in the circus that not many people can do the act like you, that your uniqueness, your measurements, your height, your weight, the way that you move. You're pretty unique, and if you understand that you are that unique then you have the world at your hands and no one can take it away from you. It's your act. It's your number. Because of that people became very personal. Something like Vesuelda de Damel, the first show, is about seven people coming together, friends from different life situations. If we watch a show for example like Traces, it started with five friends together, skateboarders, very street-wise. I mean, what happens in that community and what happens to them is the stories that we tell and they tell.

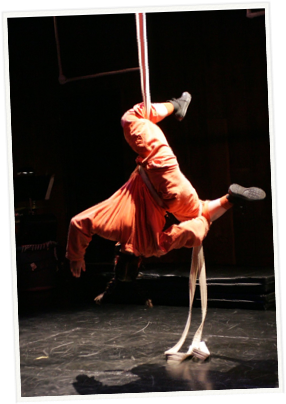

A company like Flip Fabrica is very similar as well. What we can do with the hyper-physicality though is draw the audience to such an edge in their seats, because the understanding that what is happening in front of you is inherently dangerous is an immediate draw. Where I think we should continue and will continue to push the art form is to understand what a backflip move means. What does it mean? What does it mean to do two-arm roll-ups on straps? The image itself is giving you a lot. If you understand what a two-arm roll-up is, it looks like a cross and you roll all the way up towards the ceiling. It's ascending, it's a power move but it's also grace. It can mean a lot of different things. When we go away from what we call acts, which is what we've done in contemporary circus, which is something that we still borrow from traditional circus, and we go from that to circus scenes and we stop talking about skills used within the circus scene, then we would understand that we don't need as many tricks, we would need just a few to be able to tell a story, and the story is very vividly in front of you because the human is overcoming the physical obstacles. It's literal, the problems, as I said, the obstacles are all real. No acting needed, just focus, execution and grace which comes with joy and the joy that the performer brings.

Michael: In addition to studying contemporary circus as a scholar, you're also a practicing artist. Can you tell us about your work with Pelú Theatre and The Nouveau Sud and how you're trying to apply some of the recent developments in the circus to your work with your troupes?

Carlos: With the Pelú Theatre Project, I understood pretty quickly once I moved to the continental US, I'm originally from Puerto Rico. I understood my Latino niche. I understood myself as a human but not as a Latino within a larger context of the United States. With Pelú, I tried to answer using the extreme physical language and clowning and masks and so on, to explore the reality of a Latino, Latino immigrant or living in the United States. With Pelú, what I've done is precisely what I alluded to before. There are no acts, there is not a moment when we stop the show and use the circus. The set is already there an the acrobatic elements happen within and maybe one single skill happens.

For example, we did an original show called Suicide Note From a Cockroach. The character at the end dreams that he is being killed by the human. As the character dreams he is being killed, he is ascending to heaven using a two-arm roll-up and that image looks almost crucified which is very central to Latino iconography. Then he hears the devils are coming so he goes into a nightmare of being pulled by devils, so he comes down from that, goes up again and does a drop. What we call a kamikaze or two-angle hang drop, giving up. It's all imagery, not necessarily the skills, but we do need for that an actor that can accomplish the skills. That's an actor for me that I call the quadruple threat because you can add to that playing music, singing and dancing and acting, but also doing acrobatic skills.

Then my other side of work is a little more in line with the contemporary circus as we see it today, which is the Nouveau Sud Project. What I did with Nouveau Sud was understanding how the circus has always been inclusive. I think as I alluded before, the circus is not about how you look or what your background is, or what your heritage is. It is: can you do this skill or not? If you can do this skill and a number of skills you must be on stage. It is not a question of should, you must show that and bring it forward. So understanding how inclusive the circus has been and then moving to a city like Charlotte which had a big problem of cultural segregation. I went to different community sectors and started teaching circus arts in different places, and I mixed, for example, Mexican dance with dance trapeze because the spinning action mirrored for me the action that they do with the skirts, so they added that element. The great dancers did some wheels, some acrobatics, and some straps, and so I did that with several sectors in the community with the hope that we will bring these communities, with their newly developed skills, which were a mix of new and traditional circus elements, together, so that we become a unified voice.

The troupe has grown and now we're working on our third original show. I think the power of it is that its a homegrown initiative. It's a very talented group of people, former community members now professionals, who are very well aware of their bodies but are also well aware of who they are in this community, that is still segregated. They know when we come together we serve as an example for the community at large and therefore we also have the door to talk about social issues.

Our last show, for example, dealt with deportations and police brutality. During the deportation when the guy ends up alone, he does a hand balancing piece in grief of loneliness. Hand-balancing is a very isolating training and act. It is a person alone and it requires a ton of time, all of that is embedded. Hand balancing gives you that sort of alienation and loneliness for lack of a better term. We ended the show with a wheel act, which is a single spinning wheel which is very energizing for the audience and the character ends us being killed by the police at the end after the audience is so with the act. That was one where we were able to use the circus to entertain and push a social conversation through understanding what each circus act and practice means. With Pelú, we use circus elements to enhance a theatrical performance.

Michael: We'll post links to information about the contemporary circus in our show notes. Carlos, thank you so much for being here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Not to be pedantic but Carlos Alexis Cruz is a professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, not South Carolina.

Thank you, we've made that change in the transcript!