We live in a time almost unparalleled in our consciousness of social justice. Millions and millions of people, from the global north to the global south, understand the existential threat of climate change, of perpetual war, of perpetual patriarchy. We understand that, absent a course correction, we are headed into a future that is dim in prospects for food security, human rights, quality of life—for any life at all.

And yet global decolonization and de-patriarchalization remains as elusive as ever. The battle of Standing Rock reminded us that human rights violations against people of color and ecocide grow up together; a deforested and Indigenous-less Amazon would almost immediately spell a global climate tipping point, reversing the rainforest’s attributes as net-remover of carbon and accelerating the greenhouse gas effect exponentially. Traditional Indigenous territories inhabit 22 percent of the world’s land surface, an area that contains 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity. Amidst threats of mass extinction, Indigenous communities from Standing Rock to Suriname to Bolivia have vowed to continue their centuries-long work against environmental destruction by vowing (and succeeding) to battle gas companies, loggers, governments, and cartels.

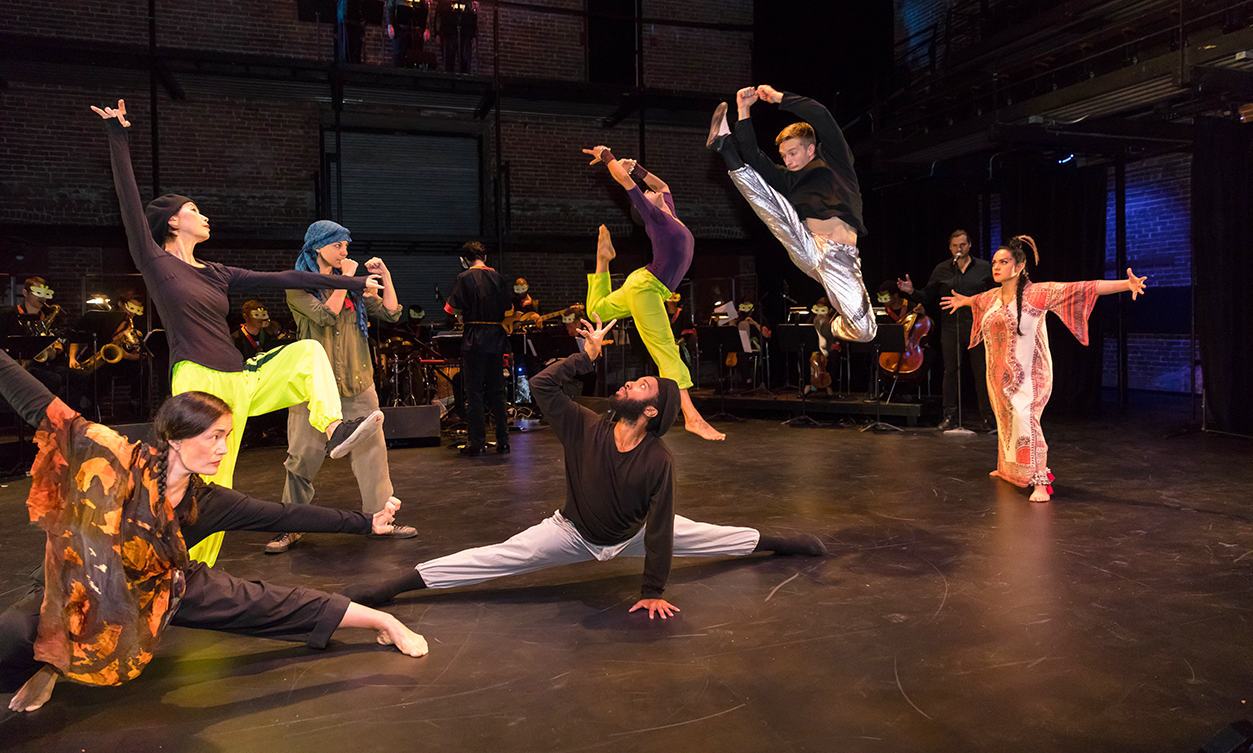

As musician-activists—self-called “artivists”—based in the United States, we wanted to develop a collaborative jazz opera rooted in the defense of nature and Indigenous social movements. After taking part in the Community Supported Art Series residency at New Hazlett Theater in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, we decided, alongside our collaborative team of Peggy Myo-Young Choy (choreographer) and Ruth Margraff (librettist), to create a devised work that integrated the political vision, sacred insects, sacred plants, and values of three revolutionary women: Reyna Lourdes Anguamea (of the Yaqui nation based in Sonora, Northern Mexico), Azize Aslan (of the Kurdish Freedom Movement), and Mama C (a veteran of the Black Panther Party, now doing community work and homesteading in Tanzania). These three remarkable women became our friends, allies, and comrades as we conducted interviews, workshopped the script, and set the piece to music. Having their voices at the center, rather than as subjects we hoped to represent, made this opera an organic expression of social movements as opposed to a study of artistic colonial anthropology.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here