The professional theatre industry in Malawi dates back to the late '60s, with the establishment of the drama department at the University of Malawi, Chancellor College in 1967. Ever since Wole Soyinka’s The Trials of Brother Jero, which is cited as the first play staged at the university, the industry has been growing. For a long time, it was male dominated.

This can be attributed to the way our society has perceived female actors. Audiences here have long thought that only women with loose morals would ever be performers. Imagine growing up in an environment where female actors are labeled “prostitutes”; imagine being female and gathering the courage to tell your parents that you are joining an acting group. Not an easy thing to do when the responses were harsh. That was the fate of many Malawian female actors and sadly still is in some circles.

The last few years of the '90s were polarizing because, despite the judgment female actors faced, that was when they started taking leadership positions. The late Gertrude Kamkwatira (1966–2006), a playwright, director, and actor, led a group called Wakhumbata Ensemble Theatre and later founded Wanna-Do Theatre. She rose to become the president of the National Theatre Association of Malawi (NTAM), producing plays that challenged the status quo and criticized the Bakili Muluzi and Bingu wa Mutharika governments of the day. Malawi had just divorced itself from a thirty-one-year dictatorship deal, and freedom of expression was the talk of the town—even though some people were arrested for speaking ill of the government. But Kamkwatira and directors like her faced the regime head-on. Their courage inspired other women, like Joyce Mhango Chavula, into full-time acting.

“I always marveled at how a female like Kamkwatira was so good at her craft, and how she always seemed to enjoy herself on stage,” explains Chavula, who, as a secondary school student, would watch Kamkwatira and her group perform.

When Kamkwatira died in 2006, the industry returned to being male dominated for some years before Chavula decided to rise up. She quit her professional job as a sales and marketing supervisor in one of the local media houses in 2009 and, the same year, launched Rising Choreos Theatre Company, having decided to permanently follow her passion of dramatic arts, a dream she had been harboring since her secondary school days.

In Malawi, a developing nation that ranks in the top three of the poorest countries in terms of GDP, it was an insane decision. Jobs were hard to get and theatre audiences had started dwindling, compared to the late '80s and early '90s when audiences used to fill performance halls. But her choice paid off.

Audiences here have long thought that only women with loose morals would ever be performers.

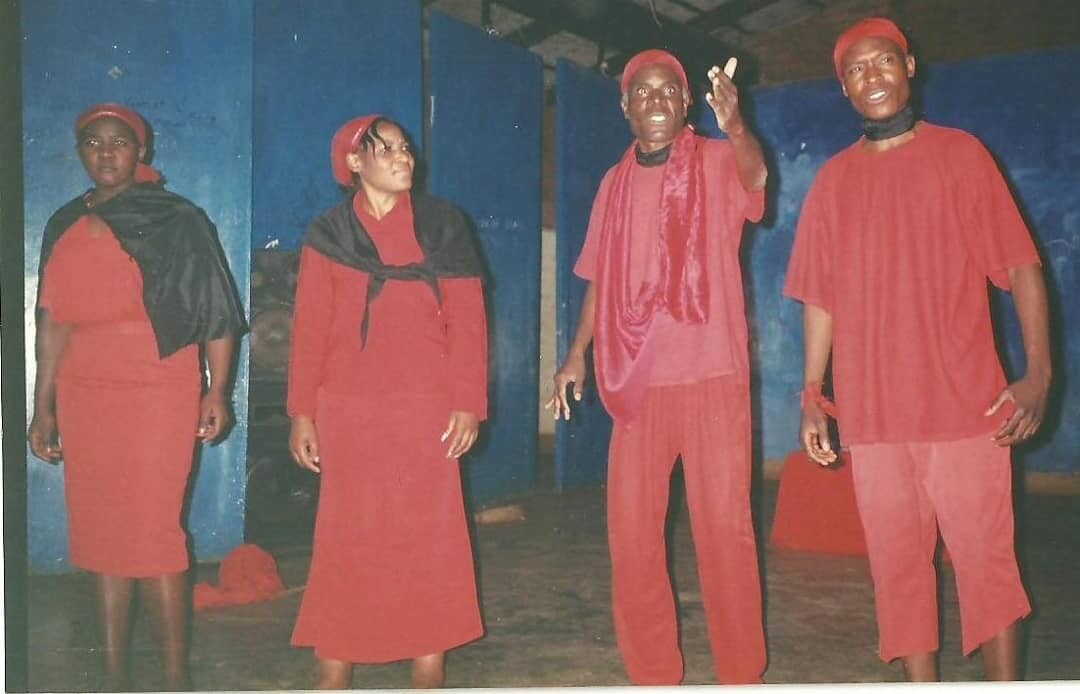

In 2011, Chavula’s company began working on an intercultural theatre performance called The Return, which would bring together a Nigerian and Malawian cast and would tour to all three regions of Malawi: the southern, the central, and the northern. The writing process took her over six months, after which they put a call out for auditions. Well-known Nollywood actress, Patience Ozokwor, who had done theatre prior to working in film, joined the team.

“Our rehearsals took almost two months, and when Patience arrived, we had a two-day rehearsal with her,” says Chavula of the show, which she also acted in. “All our shows were sold out.”

The success of this production, which was her second, overshadows the great challenges she has faced as an actor in general and as a female actor in particular. The first is a lack of proper infrastructure in the country, which would allow theatre creators to practice their craft with ease. For example, having no arts school in the country—Chancellor College just has a drama department—has led to a lack of skilled artists. Even people who study drama at Chancellor end up not working in the field because theatre does not pay much.

The other challenge is that there are few women in leadership positions in the industry. Chavula believes that if the number were higher, more and more women would be empowered to work in the arts. “Maybe just three percent of women are in leadership positions,” she says. “[For three years] I served as the vice president of the NTAM and I tried to influence women to do more, but it remains an uphill task. I am glad to see an improvement in this area but there is more that needs to be done.”

Chavula, now a board member of NTAM, has reservations about the current status of theatre in her country. She feels it is not satisfactory; instead of moving forward, it has gone in the opposite direction, and there is a huge gap in representation. Public perception of women in the arts still remains negative. “This is the barrier we all need to break,” she says. “Women have the right to pursue their dreams just like men.”

Harriet Kanyenda, the chairperson of the Actors Welfare Initiative, adds sexual harassment to the list of challenges women actors are facing in Malawi. She feels that male directors take women for granted in Malawi, and that most male directors ask for sexual favors in exchange for leading roles in a theatre piece. “As a married woman it is a very big challenge, because most husbands do not see acting as a career,” she says. “Once you get married your acting dream ends, as 95 percent of Malawian men would not allow their wives to continue acting.”

Inspired by the #MeToo movement, and borrowing from Eve Ensler’s Vagina Monologues, [the Chitenje Changa Monologues] is giving Malawian women a platform to express themselves and open up about sexual harassment.

Echoing Kanyeda’s sentiments on sexual harassment in the industry is Roselyn Dzanja, a drama graduate from Chancellor College. Since her graduation in 2017, she has been looking for drama-related work. “Most of the offices I went to, the men—either the owners of the organization or other senior employees—demanded that I have sex with them or start a sexual relationship with them. I reported these issues at the labor office and was shocked when a woman there told me to just accept these things or otherwise I won’t get a job, because that is the way things are these days.”

Dipo Katimba, a Malawian actor whose credits include performances on international stages in Germany and the United Kingdom, doesn’t think actors can sustain themselves in Malawi. “You can’t even pay rent or afford to buy daily food from the money you make from acting,” she says. “Actors have to rely on gate collections to survive and with the dwindling numbers of audiences the money you get is not that much as well.”

One interesting development taking place in the theatre industry, something led by a woman, for women, is the Chitenje Changa Monologues (CCM). (A chitenje is the traditional wrapper worn by women in Malawi). Inspired by the #MeToo movement, and borrowing from Eve Ensler’s Vagina Monologues, CCM is giving Malawian women a platform to express themselves and open up about sexual harassment. According to the founder of the movement, Zilanie Gondwe, CCM is an intimate examination of the hopes, dreams, joys, and pain of being a Malawian woman: a daughter, wife, mother, and the many other roles that women play.

The first show premiered in November 2017 at the MADSOC Theatre in Lilongwe during the sixteen days of activism against gender-based violence. Since then it has been performed at Chancellor College as part of the Lake of Stars festival and will soon be performed across the country. “It is a platform to increase sisterhood, promote healing, and release the voices that have been stifled,” Gondwe explains. “The cultural taboos around some topics need to become extinct in order for girls and boys, women and men, to live fuller and happier lives.”

There have been lots of ups and downs in Malawi theatre over the past fifty years. But despite the challenges, strides are being made. There has been a recent birth of new theatre companies in Malawi, some of which are being run by women. And the current vice president of NTAM is a woman, Rhoda Malowa, as is the president of the Actors Welfare Initiative, Harriet Malili.

Katimba believes there is hope for the future for female actors. “Every industry takes its time to grow,” she says. “The efforts we are putting in now will usher in a new future where both men and women practice theatre without constraints and without being judged.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here