The radical inclusivity of Fierce went beyond the play itself. The way the team, alongside FringeArts, made the production as accessible as possible and communicated that to audiences was the most holistic approach to creating belonging that I have witnessed in a theatre thus far, and it seemed to yield an audience that was ready to go along. But this openness brought to mind a wholly different experience I had had around theatre accessibility and audience reaction. I was working in the box office at another Philadelphia theatre company, and we had sent out an email reminder to patrons that the upcoming matinee they were attending was a relaxed (or sensory-friendly) performance: house lights would remain on at a low level, people could talk or move about as needed, lights and sounds in the show would be adjusted slightly, there would be designated quiet spaces in the lobby, etc. One angry patron called immediately to switch her tickets so that she could attend a more standard, non-sensory-friendly performance. And while her rage might have been disproportionate, I could see why she was upset. Her expectation when she bought her tickets was that she would go to the theatre, the lights would go down all the way, and when the show began she would be another anonymous theatregoer in a sea of observers, watching a world that was separated from her by the lip of the stage. Everyone would be quiet, and there would be no room for distractions. Audiences have been taught that this is how a night of theatre-watching should go, and anything else in a sit-down affair is an aberration.

However, at that same box office, I had audience members who would have defined themselves as neurotypical or not having a disability tell me they didn’t notice a difference between the relaxed performance and any other performance. Though the “rules” of theatregoing had been loosened, their experiences were not negatively impacted, nor their enjoyment diminished. But even if the environment of the room had been noticeably altered to them, would it have been a stark contrast from what audiences experience in theatres every day? There are the people who talk loudly to their comrades, that guy who gets up in the middle of a scene to use the bathroom, and the woman who takes a full minute to open a cough drop. We are ready to accept those disturbances, but have a tougher time employing the same acceptance and extending our compassion to those who might need more flexibility.

Though the “rules” of theatregoing had been loosened, their experiences were not negatively impacted, nor their enjoyment diminished.

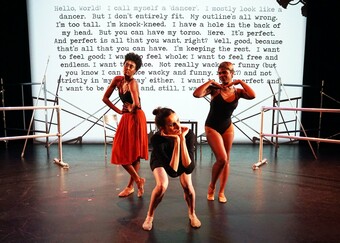

At the performances of A Fierce Kind of Love, the rules had been changed. And what did it cost me? Other than the price of an industry rush ticket, not a damn thing. In fact, I would say that my experience was all the more enriched. I felt encouraged to see more of the space, talk with my neighbors, and lock eyes in moments of solidarity with fellow theatregoers during the performance. So why do we fight for that which is inherently restrictive to many members of our community? Why are we compelled towards a confining decorum?

In the long history of theatrical practice, this kind of polite spectating is but one way to witness theatre. After all, audiences in Elizabethan England stood packed in front of the stage, commenting and hurling insults (and sometimes food or other objects), and shoving each other for better viewing spots. I’m not necessarily saying that we should instigate a mosh-pit mentality in our audiences; I’m sure actors appreciate not having rotten food thrown their way. But the point is we have not always needed quiet solitude to appreciate art. Even today theatregoers are attracted to shared thrills, human contact, and deviations from our comfort zones, something made clear by the popularity of immersive pieces like Sleep No More and Then She Fell.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here