Introducing A Polish Theater Cookbook

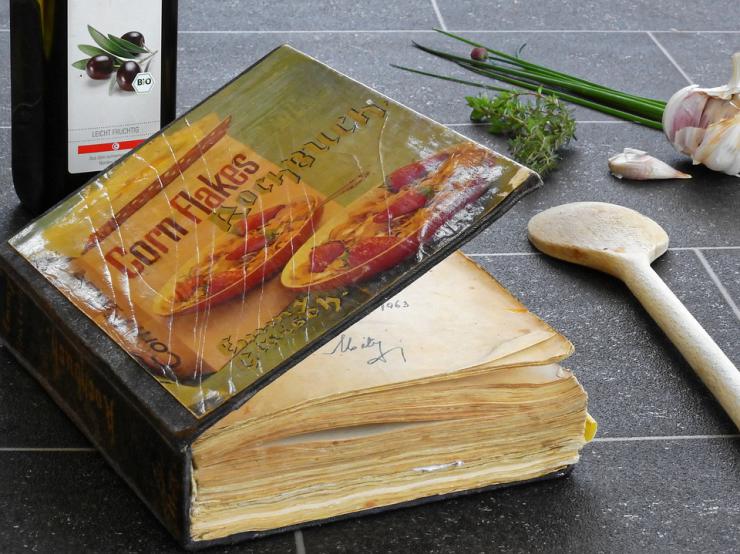

Dara Weinberg reports from rehearsal rooms and interviews with directors in Poland; how US artists can modify or adapt Polish techniques for their own kitchens.

Theater is important to people in Poland the way food is important to people in Italy.

Artistic expression in Poland is about more than artistic expression. Poetry, music, and writings from exiles, from Mickiewicz to Miłosz, helped to preserve Polish language and identity during years—centuries—of war and oppressive regimes. As in other states in the region—such as in Estonia, where the "Singing Revolution," a nationwide protest through traditional vocal music, ended the Soviet era—in Poland, the arts have historically had a role in politics.

The third Polish Republic will be twenty-five years old in 2014. The culture is no longer under active threat of being wiped out. But Polish actors and directors still go to their rehearsal rooms, to their theaters, as if their lives depended on it.

They take great pride in what they do.

This cultural pride is more important than the red herring of state funding. Great Polish theater has scraped its way into existence from stateless, state-in-exile, or state-straightened circumstances. European Union coffers can't take credit for the Polish theater tradition.

To this end, after two years hanging around Polish theaters, this series, A Polish Theater Cookbook, is my ongoing attempt to describe what happens in those rehearsals—and to suggest a few modifications for our own use.

For those of us who admire their work and would like to borrow from it, this is good news. We don't have Europesque state funding. But US practitioners have a chance of cooking theater as the Poles do without any change in our execrable funding situation or in the value which is generally placed by our culture on the arts in general and theater in particular.

The cookbook metaphor has helped me to explain this both to myself and to others. You don't have to move to Italy to cook a good bowl of pasta. You can make Italian-style pasta with the ingredients you have at hand. All that is necessary is a recipe.

And a different attitude in the kitchen.

To this end, after two years hanging around Polish theaters, this series, A Polish Theater Cookbook, is my ongoing attempt to describe what happens in those rehearsals—and to suggest a few modifications for our own use.

One caveat before I begin: I am not concerned with painstakingly documenting every single thing that Polish artists do in their theaters. Plenty of academics, from Poland, the UK, and elsewhere, are working on that. I am interested in that project, and have sometimes contributed to it. But this is a cookbook. Cookbooks don't have to have academic credentials, or any pretense of comprehensiveness.

I am going to indulge in personal digressions, make changes, omit things, and be selective—I will mostly focus on the recipes that I would want to cook myself. The Polish language does not have articles ("a," "the"), but I have deliberately called this "a" and not "the" Polish theater cookbook.

To balance my own bias, I am going to alternate my descriptions of Polish theater, in this series, with interviews with Polish artists.

All that being said, in my avowedly biased opinion, the broadest general principle differentiating Polish theater cooking from ours is that Polish artists take more risks in the kitchen.

Here are a few examples. I don't mean to say that every production in every theater always does all of these things. But I have seen each of these things happen on multiple occasions.

1) No rehearsal schedule to speak of. A schedule which changes so often as to not permit any advance planning. Maybe you don't know what the day off will be, or when it will be.

2) No rehearsal breaks whatsoever—or, there may be a break, but there is no agreed-upon notification of if there will be a break and, if so, how long it will be.

3) No agreed-upon end point; no expected limit on the number of hours you can rehearse in a day.

4) Directors frequently give readings of lines and movement to performers.

5) Directors sometimes conduct performers live during performances.

6) Directors often perform in their own shows.

7) The text is treated as a point of departure, not a sacred object.

8) Copyrighted material is sometimes used without permission (though not nearly as often as it used to be, or as much as is often perceived by outsiders).

I've tried some, but not all, of these techniques, myself. Some of them are too weird for me, and I will never try them. (I will say whether or not I have attempted something myself, when I describe a recipe.)

But I believe I am a better director because I have learned to incorporate a few elements of Polish-style cooking into my rehearsals.

Theater tastes different in Poland, in the way in which pizza in Palermo or Pisa tastes different from a frozen Trader Joe's pizza incarnated in the microwave. I have nothing against Trader Joe's—I love it. But it is not the same thing.

In Poland, they are making theater from scratch. Whether or not we intend to do this ourselves, I think it is useful—as an exercise—to imagine it.

I am a ravenous reader of cookbooks but a very lazy cook. I have never done everything that Nigella and Nigel tell me I should do to the duck. But when I am defrosting the 500th boneless skinless chicken breast in the last 501 days, I think about those books, and I cook a little differently. Different spices, different timing, a longer marinade, more heat. Something.

Usually, I just make up my own recipe. I'm a director, after all, and I hate it when people tell me what to do.

Do teatru! (To the theater!)

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for this very interesting and informative series. You have every right in the world to offer your own exploration of what you found in your observations - and I appreciate your sharing your experiences and conclusions. They can be agreed with or disagreed with, but having them out for view and discussion is invaluable.

Thank you, Lisa. I'm very glad you are finding the series interesting. I will do my best to keep sharing what I've observed, as objectively as possible.

I applaud the intention and perhaps the cooking metaphor works in a different context. It worries me that half of the "techniques" involve violating labour laws or copyright agreements. Those things, along with apparent lack of respect for collaborating artists that other "techniques" imply, are not the basis of making art.

Dear Kathleen, thank you for your comment. I am also concerned about the ways in which Polish theater rehearsal practices might violate US regulations or laws related to labor. My goal in presenting these practices is not to advocate that US artists do exactly the same thing as the Polish artists, but rather to modify these techniques so that they can work within our legal and cultural framework, without violating any US laws.

However, I am also going to do my best to describe the original Polish version before suggesting modifications.

Also--I did not mean to imply any lack of respect for collaborating artists in Poland. If I said something that implied that, that was my mistake. There is great respect in Polish rehearsal rooms for all the practitioners. Is there something I can clarify?

Thanks for the response, Dara. When I read the next posts, it became much clearer how you intended these comments. Of course, the labour practices of Poland are rooted in very different assumptions than those of North America. It might be useful for all of us to look at the way work is structured in various places in order to replace the industrial model our systems (English Canada too) are built on while maintaining reasonable pay and respect. Artists are workers, often working for others, and we don't want to go down the slippery slope of "you like it so much you should do it for free".

Dear Kathleen, I agree that examining the history of work in a culture or nation, when examining things like rehearsal structures and scheduling, is important background. This is a great idea. I am also starting to think that a comparative study of rehearsal schedules in more cultures might be worthwhile. I appreciate your comments very much and will try to keep broadening the scope of the articles here.

Certainly, artists are workers, especially professionals and adults. But I think there are some situations--people who sing in church or synagogue choirs, for example, or children who act in school plays--where their artistic cooperation can be defined on different terms than that of "work," and where lack of payment doesn't constitute a problem. I do not want to go down that slippery slope, either, but I will admit that I have continued to do unpaid work myself, in theater, even as I have done paid work. It has been my choice to do so. I don't want any professional performer to go unpaid or feel that he or she is being asked to do so. But I also want us to, when discussing art, acknowledge that there are people who participate in art as talented amateurs, and that our discussion of art should include their contributions too. And I think that a professional--and I sometimes am a professional--can also choose to sometimes work in an "amateur" or unpaid setting, if he or she wishes. Would you agree?

I like the cooking analogy. Be it the theatrical equivalent of meth, borscht, or an old shoe, we're cooking it and someone else has to consume it. Isn't that what Jerzy Grotowski deemed the essence of theatre?

As for techniques. To me that is a term you apply when you want to alter a rusty routine. How do you get kids who have been brought up in the rather hierarchical American theatre tradition to put aside a text or ignore a director? You have to apply a technique and practice.

I like theatre because in that empty space you are allowed to forget every rule and ignore all traditions. What I get from this cookbook preview (can't wait) is that it is OK not to worry about how it's going to taste. If you use quality ingredients, proper cookware and understand the process, you have no need for a 'recipe' or a 'chef' to create a delicious meal.

Dear Gerhardus, thank you for your comment. I like the idea of "meth, borscht, or an old shoe" very much!

Yes, that is how I was thinking of "techniques."

The cookbook metaphor seems to have been appealing to some people and off-putting to others, but my intention was to do what you say: to take away practitioners' concerns about perfect execution or limitations.

I hope you enjoy the series.

Perhaps well intentioned, but the central tenet of this project -- "[...]how US artists can modify or adapt Polish techniques for their own kitchens" -- strikes me as seriously misguided. To say nothing of the Orientalism underlying the endeavor, "Polish theatre" is not homogenous, and it's not possible to create a recipe/check-list for making it. The initial ingredient list above includes "techniques" (more like a bag of tricks) of a dubious nature, as well as items pertaining to working conditions that are more likely idiosyncratic happenstance of a particular director or project development situation rather than properties of national practice or aesthetic. The decontextualization and oversimplification of the items listed via the cookbook metaphor spells a recipe for disaster -- especially when put into the hands of people who don't have a clue regarding context and/or are lacking the intellectual/artistic fortitude/background/sensitivity to employ the ingredients tastefully.

Remember what happened when an incomplete and oversimplified view of Stanislavski's work made its way to America? (By the time the Moscow Art Theatre was brought to America, Stanislavki had already evolved his practice beyond a restrictive emphasis on psychology.) We got what has become the very limited, complacent, hegemonous banality so ubiquitous on American stages today. We did not get the quality of work/inquiry actually fetishized by those admirers of Stanislavski who sought to bring his techniques to America. We did not get the kind of work/inquiry more likely to be found today in places such as Central and Eastern Europe, where Stanislavski's legacy-in-action accounts for a more holistic transmission of his teaching and theories and, perhaps most importantly, has fostered a spirit of continuous inquiry/research and a conviction that -- more than just being a well-made story or an object for consumption -- theatre art actually can DO something.

It is impossible to substitute for the social, political, religious, historical, and practical contexts in which Polish theatre practice has developed. It is impossible to replicate the cultural environment and rich artistic legacy into which Polish people are immersed from birth and within which their artistic development is shaped. It is a fallacy to suggest that someone can take ingredients x, y, z and create Polish theatre or anything approximating it.

This does not mean I think Weinberg should scrap the project completely. I would encourage Weinberg to focus on the portion that includes reporting from rehearsal rooms and interviewing directors ... but to eliminate the cookbook component. Where there is an impulse to hold some "different" technique forward in a how-to fashion, instead consider exploring the systems (government and otherwise) which may have contributed to its development. Consider anything else, please, besides implying that there are quick tricks, simple steps, or even a coherent method for "cooking" theatre like they do in Poland.

Finally, I encourage Weinberg to consider being more mindful to language. Not every point of difference merits the label "technique." Moreover, referring to techniques as "weird" both polarizes and others your subject.

Absent the prescriptive component, I believe Weinberg's project has the possibility of making a positive contribution to our understanding of theatre in Poland today.

Dear Ms. Lavy,

Thank you for your detailed comment. I am going to respond point by point; I welcome the opportunity to enter into a discussion with you.

You write:

(1) "the central tenet of this project -- [...]how US artists can modify or adapt Polish techniques for their own

kitchens" -- strikes me as seriously misguided. To say nothing of the

Orientalism underlying the endeavor, "Polish theatre" is not homogenous, and it's not possible to create a recipe/check-list for making it."

My response to this:

I believe there is a place for multiple kinds of writing about theater: (1) reviews and critical descriptions of what exists, as it exists, in a specific performance, typically without reference to how it was created or how practitioners might try to learn from it,

and

(2) descriptions of rehearsal processes from which practitioners can try to learn.

This series falls into the second category. By doing so, it fails at achieving the goal of the first category, but I do believe there is room for both kinds of writing. I have written articles elsewhere that are critical reviews and descriptions of Polish theater, trying to describe it as specifically as possible. I value and participate in the first kind of writing. This series attempts something different.

I would never refer to Polish theater as homogenous; its diversity is extraordinary. However, I do believe that there are a number of marked similarities between certain Polish practitioners, particularly the post-Grotowski theatres (discussed further in the second installment of this series) and that it is possible to highlight some common features.

Finally, I do not suggest that US practitioners try to re-create Polish theater in the US. I suggest that they learn from certain Polish practices which are useful and interesting, and which could be effectively used to change some US rehearsal dynamics. I do not consider this to be an "Orientalist" suggestion on my part; I do not suggest imitating, copying, mocking, artificially idealizing or inaccurately generalizing about Polish theater. What I do suggest is that US practitioners learn more about Polish theater rehearsal practices, so they can determine if any of these practices might, with some modification, be useful in their own work.

You write:

(2) "The decontextualization and oversimplification of the items listed via the cookbook metaphor spells a recipe for disaster -- especially when put into the hands of people who don't have a clue regarding context and/or are lacking the intellectual/artistic

fortitude/background/sensitivity to employ the ingredients tastefully."

My response:

When writing a summary list, or a general introduction, some simplification is, in my opinion, required--particularly when writing for a non-specialist audience. However, as the series develops, I will be using more and more specific examples in context and in detail.

Yes, many of the elements with which post-Grotowski Polish theater practitioners work seem as if they might be disastrous in the hands of unprepared practitioners. My goal with this series is to suggest some modifications to post-Grotowski Polish theater techniques that might make them suitable for, for example, a classroom. I believe that even these advanced methods can be learned from at many levels of practice.

You write:

(3) "Remember what happened when an incomplete and oversimplified view of Stanislavski's work made its way to America? (By the time the Moscow Art Theatre was brought to America, Stanislavki had already evolved his practice beyond a restrictive emphasis on psychology.) We got what has become the very limited, complacent, hegemonous banality so ubiquitous on American stages today."

My response:

For one thing, several of Grotowski's productions and several post-Grotowski productions have already come to the United States, multiple times--for example, Teatr Zar and Studium Teatralne have toured. So US artists and audiences have had the opportunity to see this work in its original form. Some of this work is also available online.

However, what I think most US practitioners have not had is an opportunity to understand how the work is put together--a glimpse into rehearsal process.

It is not my intention to cultivate banality, or to oversimplify the complexities of Polish theater. It is, however, my intention to write about some of its most interesting rehearsal methods in a way that is accessible to practitioners who are unfamiliar with it.

You write:

"It is a fallacy to suggest that someone can take ingredients x, y, z and create Polish theatre or anything approximating it."

My response:

I thoroughly agree that the cultural context cannot be replicated, and I did not mean to suggest that anyone should attempt to replicate it.

However, I do believe that it is possible for US artists to learn new rehearsal practices by attempting some different methods. The result will not be Polish theater; it will still be US theater, but with some different features.

You write:

" I would encourage Weinberg to focus on the portion that includes

reporting from rehearsal rooms and interviewing directors ... but to

eliminate the cookbook component. Where there is an impulse to hold some "different" technique forward in a how-to fashion, instead consider exploring the systems (government and otherwise) which may have contributed to its development. Consider anything else, please, besides implying that there are quick tricks, simple steps, or even a coherent method for "cooking" theatre like they do in Poland."

My response:

I will certainly continue to report from rehearsal rooms and interview directors, but I do not intend to eliminate the cookbook component.

I respect your strong discomfort with the idea, and am glad to have heard your argument, but I would respond that not all cookbooks are simplifications. I think that a description of the steps taken to achieve a result is a worthwhile critical task. I do not think that "cooking" theater in a manner inspired by post-Grotowski Polish theater rehearsal practices is simple, quick, or easy. I will not be arguing for a coherent method, or even for a "how-to." I will be describing practices.

As for exploring the "systems (government and otherwise)" which have contributed to the development of Polish theater rehearsal practices, I will certainly refer to this historical and sociological material when it is necessary to understand the rehearsal practices. However, I believe that providing a comprehensive overview of Polish history, and how Polish politics have affected theater in the country, is outside the scope of this particular series.

You write:

"Finally, I encourage Weinberg to consider being more mindful to

language. Not every point of difference merits the label "technique."

Moreover, referring to techniques as "weird" both polarizes and others your subject."

My response:

I disagree that the points to which I refer in the list cannot be considered to be techniques. It stretches the word's traditional usage, but I believe the word can handle it.

As for using the word "weird," I have intentionally taken a very informal, casual tone in this blog series. In this particular instance, I was attempting to colloquially express some of the discomfort which US practitioners often feel, in my experience, upon hearing about Polish theater rehearsal techniques, particularly those relating to rehearsal scheduling.

It was not my intention to polarize or other my subject, but if that is how it read to you, then it is my error, and I apologize.

Finally, you write:

"Absent the prescriptive component, I believe Weinberg's project has the possibility of making a positive contribution to our understanding of theatre in Poland today."

My response:

I do not intend for this project to be prescriptive or reductive; I intend for it to first describe existing post-Grotowski rehearsal practices, in detail, and then suggest how US artists might modify some such practices for their own use. However, I respect your discomfort with this idea, and I can only say that I will try to carry it out sensitively, and with as much reference to detailed examples as possible.

Thank you for your comments; I too hope to make a positive contribution.

I will finish by saying two things.

First, I am aware that writing about theater in this manner, with a focus on rehearsal methods rather than on describing performances, has not often been attempted. I do not claim to be able to do it perfectly, and I am aware that it is unusual, but I do claim that it is worth making the effort.

Second, I am writing this series in direct response to the questions of many practitioner friends who have asked me for more detail on rehearsal practices. These people clearly are interested in how they may learn from post-Grotowski Polish theater work. I do not agree that it is a mistake on my part to try to answer their questions, in a format which will be accessible and useful to them--geared for practitioners. I may fail at this endeavor, but I do not intend to give it up before I start.

wspaniały!!

dziękuję!!

I'm super excited about this series! I can't wait to read more!

Dear Jacob, thank you--I'm looking forward to writing more.