Letters from Canadians to Americans

Aislinn Rose

Recently, all eyes were on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau as he paid a visit to the new President of the United States of America, Donald Trump. With our two leaders sitting side-by-side for a polite photo shoot, we had to wonder: what distinguishes us? What makes us the same? What will happen to NAFTA? Will Trudeau continue to withstand Trump’s handshake?

Across the much-discussed border, we are exchanging letters; Letters from Canadians and letters from Americans. CdnTimes will publish letters from Americans to hear what it’s like on the ground, now, for theatre artists working in the United States. Meanwhile, HowlRound will be publishing letters from Canadians about what’s affecting our work now. Artists from both countries share warnings, worries, strategies of resistance, generosity, and advocacy—messages of solidarity. What can we learn from each other? —Adrienne Wong and Laurel Green, co-editors at SpiderWebShow’s CdnTimes.

Read the Letters to Canadians from Americans on CdnTimes here.

Dear American friends,

I met my white fragility in Washington, DC.

On Tuesday November 8, The Theatre Centre was opening a new production emerging out of our Residency Program. When planning for this opening, we realized something else would be happening in the world on that same day. We decided to do what we'd done for the last Canadian federal election: we offered up our café/bar to the public for an election results viewing party. “Party.” Those people who had come to see the opening night performance could stay to celebrate the show, and join others who had come to watch the election results in the company of friends and strangers.

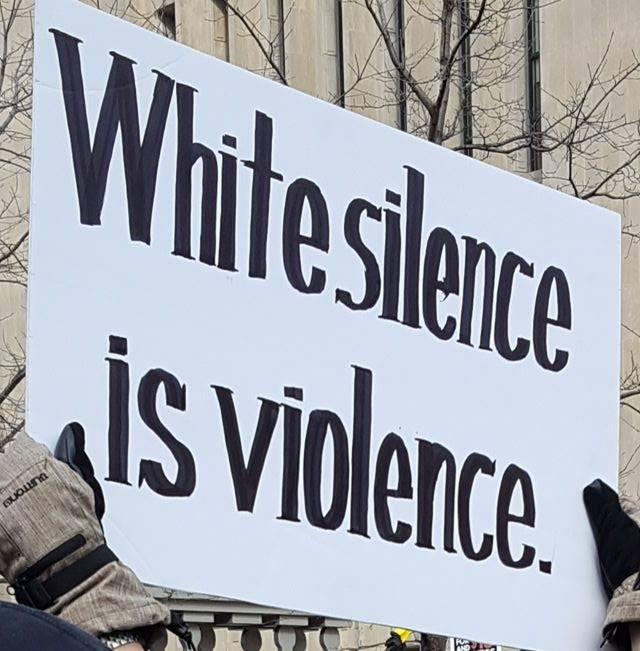

I had felt like both participant and witness at the rally in Washington. I noticed the whiteness of the event (and our bus of Canadian women) and felt troubled by it...53 percent of white women voted for him. 53 percent of white women chose white privilege.

People didn’t necessarily want to be alone that night, and offering up our building as public space is normal practice for us. We consider ourselves stewards of our beautiful city-owned building (formerly a Carnegie Library), and at the core of everything we do, we try to ask ourselves, “What can a theatre be?” We hope that a spirit of generosity guides and instructs our decision-making. But it’s hard. Sometimes it’s easier to say, “No, we can’t do that for you.”

The day after the election, I kept finding myself frowning at white men on the street and smiling (sadly?) at every person of color that I passed. I cried to a friend on the phone at the discovery that 53 percent of white women voted for this man. I couldn’t shrug that off. I can’t shrug that off. White women were more worried about losing their white privilege than they worried about losing bodily autonomy. They are more comfortable with the patriarchy than they are with racial equality. They are comfortable enough with racism.

I want to acknowledge here that the shock and pain I experienced in this moment of realization is, in itself, also insulting. If I am shocked to discover the extent of racism and bigotry in this world, then am I not also admitting I’ve never truly believed the daily experiences expressed to me by the POC, LGBT, and indigenous people in my life?

A long-time mentor of mine organized a charter bus to take a group of women—mostly from the Toronto arts community—to Washington, DC for the Women’s March the day after the inauguration. The seats filled immediately. We were keen to ensure this man would not be normalized, and we wanted to help Americans tell the story that sometimes a smooth transition of power isn’t appropriate. On the way, we kept running into other groups who were clearly making their way to Washington for the same event—we could tell by the hats.

I’m ultimately so glad I was there, but I felt ambivalent about so many of my interactions that day. I spent the day holding up a beautiful sign that I had asked a lettering artist to make for me before leaving Toronto. “Take your broken heart, make it into art.” Carrie Fisher had said these words to Meryl Streep, who gave them to us in her Golden Globes speech. I loved my sign, but looking around I felt conflicted by my privilege at being able to think about art in this time. So many other signs addressed sexism, fascism, racism, rape, rape culture, choice. But as I made my way through the crowds during the afternoon and evening, people thanked me for a positive message, and many asked if they could take my picture with the sign. When they found out we had all come from Canada to attend and participate in the rally and march, Americans seemed both surprised and thrilled. “Thank you for caring,” some said.

And then I came home. I got maybe two hours of sleep across the two nights on the bus. But I couldn’t stop thinking about my experience and how I felt about it. So many friends had seen the pictures I posted and wanted to hear all about the Washington march—but I couldn’t figure out what I wanted to say about it. In fact, it took me several days that following week to think about anything else. I couldn’t stop reading articles, think pieces, twitter threads—anything I could get my eyes on. And this:

I had felt like both participant and witness at the rally in Washington. I noticed the whiteness of the event (and our bus of Canadian women) and felt troubled by it. I was bothered by the pink pussy hats and couldn't quite articulate (at the time) why, other than the fact I've never been a fan of pink, and didn't feel any need to "reclaim" it. And then there was this image: Angela Peoples reminding me of that thing I had cried about on Wednesday, November 9. 53 percent of white women voted for him. 53 percent of white women chose white privilege.

I have not been able to stop thinking about the feminist movement since that weekend, along with my belief since I was young that it is “my” movement. I can’t stop thinking about my privilege within that movement, and about how white women often only learn about the racist history of "our movement" when we're older, having idolized many of those white supremacist leaders of feminist history for years until we are awakened to this reality.

That’s what is at issue, isn’t it, when we talk about “white feminism”? The history of the feminist movement is riddled with white women making gains on the backs of women of color. And while some (almost always white) women argue that what we need is “solidarity” in order to make real headway, what they’re really asking for is status quo.

We are not divided because we are fighting amongst ourselves, we are divided because those of us who believe we are fighting oppression don't like to hear that there are oppressed among us. It makes us uncomfortable because it makes us feel complicit. But we don't get to hold on to the privilege of waving off that discomfort anymore, because we are complicit. We don't get to keep saying, "Don't fight us, fight with us and you'll get yours," because the oppressed among us have decades upon decades of experience knowing that this is simply not the case.

Any kind of “solidarity” first requires that those of us with privilege use that privilege to center the voices, needs, and concerns of those without privilege. I know this. I try to practice this.

And at the same time, even though I'm not supposed to take these words personally if they don't apply to me, it's hard to keep hearing the words, "No more white feminism.” I understand how "white feminism" is defined, and I believe that it doesn't pertain to my own feminism, but I'm a feminist, and I'm white, and for the first time I feel like I'm floundering—not knowing what I can do/should do/am allowed to do—and I'm fragile in that floundering because I still want to feel like it is “my" movement.

And there it is. I didn’t think I had it, but I met my white fragility in Washington, DC. What now?

It’s time to step back. Listen. Be an ally. Learn how to be an ally. Be generous. But like I said, generosity is hard. Sometimes it’s easier to say, “I can’t give you that.” But generosity should be hard, otherwise it isn’t generous. When you give something to someone, you should notice the loss of that thing—that is generosity. But you do it because it is meaningful to the other person. You do it because the gain could be life altering. Experience altering. It could mean all the difference to the person receiving it. Generosity should hurt.

Adele won the Best Album Grammy the other week. She got up to the podium and said the words “I can’t possibly accept this award,” because she, too, believed that the Album of the Year was Beyonce’s Lemonade. She then went on to accept the award. Declining the award would have hurt, but it would have been meaningful. And it would have been remembered. Saying to the press, “What the fuck does she have to do to win album of the year?” is nice, but it doesn’t cost anyone anything.

Over at The Theatre Centre, where we are privileged to be stewarding our beautiful public space, our performance venues, our former Carnegie Library, we will continue to push back against ourselves when the easy tendency is to say, “No, we can’t give you that.” What can we give more of? How can we offer more space to more voices? And if it hurts a little bit when we choose to say yes, then chances are, it’s going to be a meaningful yes to someone else.

After the rally in Washington, lots of people wanted to jump up and down to celebrate the fact that the march was peaceful and there were no arrests. People of color were quick to point out that this wasn’t a thing that was special about the protest, but a thing that was special about the makeup of the protesters: this was white female privilege in action. Police show up differently to hundreds of thousands of white women marching in knitted pink pussy hats than they show up to Black Lives Matter.

So here’s the opportunity to take my privilege and offer it in a way that might hurt: I made a pledge to attend more rallies and protests specifically organized by people of color. I will put my white body on the line (when it’s wanted) in the hopes it can keep someone who doesn’t look like me safer, but I’ll take a step back when asked. To listen, to be an ally, to work on being generous.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I would venture to say that Intersectional Feminism that you speak of may be driving young people of Indo-European descent away from the Left and is the cause of the rise of the Alt-Right on our campuses. Because Intersectionality makes it so that if I write plays like Howard Barker for instance, I am "oppressive" or my very existence as a straight (Jewish) male is oppressive.

From Equity Feminist Christina Hoff Sommers

Christina Hoff Sommers (CHS): I am a strong supporter of classical equity feminism — the sort of feminism that won women the vote, educational opportunities, and many other freedoms. But on today’s campus, equity feminism has been eclipsed by fainting-couch feminism. Fainting-couchers view women as psychically fragile and prone to trauma. They demand trigger warnings, safe spaces, and micro-aggression monitoring. Their primary focus is not equality with men—but rather protection from them. As an equity feminist from the 70s, I see this as a setback for feminism—and for women. There was a battle for the soul of feminism in the 80s and 90s. The wrong side won. Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin (precursors to today’s fainting-couchers) sought to protect women from the ravages of an implacable, all-encompassing patriarchy. Never mind that no such patriarchy existed. Another group, known as sex-positive or libertarian feminists, focused on female freedom, personal responsibility, and pleasure. They saw MacDworkinism (as it came to be called) as a reactionary social purity movement. The libertarians had better arguments, but the MacDworkinites won most of the assistant professorships. Over the years, MacDworkinism has melded with “intersectionality.” Today, undergraduate women are told (depending on their identities) that they are oppressed not only by sexism, but by racism, classism, ableism, etc. Conceptually, the theory is muddled. For one thing it fights sexism and racism by classifying everyone according to sex and race. But at the highly privileged intersections of American higher education, the theory is all the rage. For an equality feminist like myself, this is a sorry development. Our feminist foremothers viewed women as just as competent and mentally strong as men, so they fought and won a battle for equality. Trigger warnings, safe spaces and identity theatrics betray that tradition, and treat women like fragile little birds in need of protection. I see too many talented, idealistic young women turning inward—away from a world that needs them.

I think that the Left needs to abandon the confusing ideology that you are speaking of. It's confusing people and making the Left unable to take action as to not "offend." But any criticism of your theories means that I am "racist" or "sexist" or showing my hard-to-prove privilege based on my skin pigment and this gets pretty confusing when you add Jewish ethnicity into the mix.

Thank you for listening.