Sustaining a Career as a Female Playwright in Ireland

I caught up with Deirdre Kinahan in Dublin, Ireland just before the opening of The Unmanageable Sisters, her first play at the Abbey National Theatre. We talked about her twenty-year career, starting with self-producing her first duologue, through her Edinburgh Fringe First winning-Halcyon Days, and the transatlantic transfer of her plays Spinning, Wild Sky, and Moment to Toronto, Chicago, Washington, and New York. Deirdre’s next play The Frederick Douglass Project will be playing at Solas Nua in Washington, DC. We talked about recurring themes of class, female characterization in her plays, and how to sustain a career as an Irish female playwright.

Pamela McQueen: You are one of very few Irish female playwrights that has had the longevity of a sustained career across the last fifteen or twenty years. As we know from the statistics garnered in the Waking the Feminist Campaign, you are a bird of rare plumage. How have you sustained that career?

Deirdre Kinahan: I was dogged. I refused to go away. I self-produced for the first thirteen years. I used to be embarrassed about self-producing, but David Greig self-produced—we all kick off that way. Some people say they don’t want to be a “female playwright.” That is absolutely fine, but I am female and I am a playwright. I am quite happy with the label.

I really think that the odds were—I won’t say are because it is shifting and it’s changing—but the odds were really stacked against you as a female playwright when I was starting out. There was this notion that persisted right up until 2016 that women don’t write the national plays. I learned so much with Waking the Feminists. What is a national play, for God sake? When I write a play set in a kitchen, it’s a kitchen sink drama. When Brian Friel wrote a play set in a kitchen, it’s a national play.

The big question is, why did it take so long? It’s a multifaceted issue. It’s academics, it’s critics, it’s gatekeepers, it’s producers. There are a lot of people who need to open their eyes, because we are losing a lot and that’s the tragedy.

Pamela McQueen: In terms of self-producing, you’ve said in the past that Hue and Cry, produced by your own company, Tall Tales Theatre Company in 2007, was your first play as a professional playwright.

Deirdre: Yes, Hue and Cry is when I found my voice, seven years in to actually writing. I knew when I was in that play that I had found something.

When thinking about Hue and Cry, I had the image of two men dancing in the final scene as they performed the ripping, a Jewish grief ritual. The whole play was a means to get to this dance. I was in a grief space. My mother had died in 2004 and I had miscarried a child. Grief was a big thing…

Pamela: It struck me as being quite brave, breaking into a contemporary dance. Did you ever doubt that when you were writing it?

Deirdre: No. I had just discovered contemporary dance through Fabulous Beast and Coisceim. Contemporary dance had been around in Ireland for fifty years, but I was just getting to know it and I loved how it told stories in different ways. I knew I had to earn it—I had to get them to the point of the dance.

Pamela: Your play Moment in 2009 is about a lower middle class respectable family. It is set over the course of a meal with a cast of nine. A fair leap technically and structurally. Was this a different writing process?

Deirdre: Moment was a big write for me—that was when I found my stride, that sparse language, where you can tell a lot in two lines. I think Moment was when I was really able to stretch out and conduct.

Theatre is deeply political for me. Drama has got to mean something, it’s got to do something to you, it’s got to make you think.

Pamela: In comparison to ordinary naturalistic dialogue, it’s very much a stripped back language in syntax and structure.

Deirdre: Yes, it is, and sometimes actors don’t trust it.

Pamela: Was there initially a holding back in early drafts of Moment?

Deirdre: If I have loads of people in a play, sometimes what I need to do is get it out, decode what it is, and throw the question out there. I’ll get my bit of plot as I float, as I walk around in their shoes and socks and tights and bras. I’ll often do character drafts. With Moment, I would very much have done that.

Pamela: It is like a layering of these characters over each other?

Deirdre: Absolutely. Every character needs a role. To me, it’s poetry, every word counts, every footstep matters, every moment’s got to earn its presence, every picture, every impulse must be there for a reason, it’s got to be pushing it all somewhere.

And then I write and rewrite and rewrite. But I find that in every single play I write there is one scene that never changes. It’s really strange, that’s always there, whether it’s at the middle, the beginning, or the end. I might rewrite around it to get to it.

Pamela: Are you always trying to intrigue the audience, make them curious?

Deirdre: I feel these are the audience’s stories that I am percolating and pushing back out at them, but in a way that makes you question your own prejudice and perception and role in this society, in this world. Theatre is deeply political for me. Drama has got to mean something, it’s got to do something to you, it’s got to make you think.

Pamela: Bogboy would be considered one of your more overtly political plays. What was your original scene idea, was it the political story or the characters?

Deirdre: I was walking through the bog and I saw a bunch of flowers out in the brown. Bogs are brown and grey in the winter and muted green, but I could see color. The vivid red was a bunch of flowers with a photograph taped to it. The photograph was of Kevin McKee—I didn’t know his name at the time—a young boy with a snorkeler jacket hood and handlebar mustache, about nineteen. It was a polaroid. I thought, what is this, who is this? Then about two days later I went back and with the rain and the sun his face had started to disappear from the picture. Then it was all coming out about the IRA Truce, and that this was one of the Disappeared and he was buried in the bog. The characters and the story often are a way to write a play about a discovery and then the form comes out of that as well. It’s usually a notion, a character embodies it and a story allows you to get in and explore it.

Pamela: Motherhood is a functioning part of several of your female characters without being the focus. Is that intentional in your drama?

Deirdre: I started to write just before I had my first baby, Siofra. Then I realized in 2000/2001 that I couldn’t continue being an actress and going on tour. I couldn’t juggle that with being a mam of a new baby. I found that writing suited my lifestyle more and I got just as much a buzz out of it. Maybe I was better at it then I was at acting. I wrote in the middle of the night. I wrote around babies. I think that’s why motherhood crops up. But it is a natural part of human evolution and life and family. It’s subconsciously naturally there.

Pamela: Motherhood featuring could be an attribute of the relatively high proportion of central female characters in your plays.

Deirdre: Again, something instinctive. You don’t quite do the gender count until you do the count. Some people were quite upset about Moment because it wasn’t all about the male character Niall, who killed the girl next door. There are loads of plays about perpetrators—but what about the perpetrator’s family? It’s that collateral, the people on the edges of trauma who are cast into these worlds and not of their own free will. They are not equipped with what you need to navigate it and they are doing their best and they are making all the wrong decisions for all the right reasons. Why does that girl need to make herself absolutely indispensable? Why does she need to pick everybody up from the hospital and drop them and make the tea? What’s under that? So, I invented the story for Ciara.

Some of the best characters I’ve met in theatre keep talking to me.

Pamela: Waking the Feminists highlighted the lack of regular production in particular for female playwrights in Ireland. That does bring us back to how you responded to that environment in the early days and again here with Halcyon Days by self-producing.

Deirdre: I was self-producing my plays right up to 2012 in Ireland.

Pamela: Is it hard, as a producer, to sell yourself as a writer?

Deirdre: Yes, it’s draining. It’s great and it’s exhausting. It’s how I evolved out of necessity. I’m good at putting money together, putting people together. I love that. I love the process of putting a group of creatives together. That really excites me. I just revel in other people’s talent. I think that’s something wonderful that comes with confidence. When you become confident about your own talent in a non-arrogant way, you can really relish in other peoples.

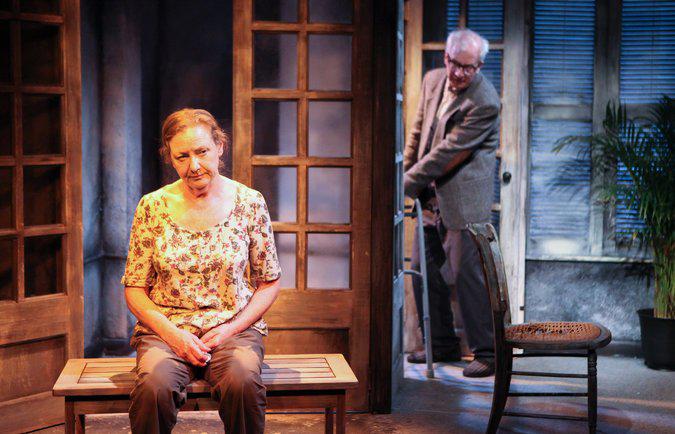

Pamela: In Halcyon Days, which was co-produced by the Dublin Theatre Festival, your characters seem to operate differently than your previous characters. They face their regrets and guilt in some way. When you are writing, do you think of the ending in advance, or do you come to it?

Deirdre: Sometimes the ending of the play is the beginning of the writing process. The dance in Hue and Cry is where I was working to the whole time. I have two rhythms for my plays. One is a train crash. The first half, you are watching that train, you know it’s going to hit the wall, and then it does. Then the second half is the aftermath—it’s where we get to explore everything that brought us to that explosion. The catharsis isn’t the ending. It’s the little flotsam bits that bring us to the ending. So sometimes I have the ending at the beginning of the process.

Pamela: An open approach to ending, is that your intention?

Deirdre: Oh yes, because I don’t make decisions. The plays are questions. The lights go down but the characters should stay in your mind. I would like them to continue to live on in your heart and your head, keep talking to you. Some of the best characters I’ve met in theatre keep talking to me.

Pamela: Your next play was Wild Sky, commissioned by Meath Council. Was your approach to making this play driven by research into the local history of Meath?

Deirdre: Yeah, it was terrifying. Writing a play about 1916 for the centenary commemoration project was pretty frightening. Everybody has their own narrative around it. Everybody will want to tell it a certain way. I needed to find my own truth in it. And not be afraid of getting it wrong, not be afraid of pissing people off, not be afraid of taking people on. Revisionism was a huge part of the celebrations and this idea of we’ve got to embrace the RUC and the British soldiers. I found myself getting myself a bit annoyed about that. Did we really need to include them—I was taking my pitchfork out of the back of the car.

I wanted to look at what was 1916? It was a popular revolution. It was the real thing. It happened in slow motion, a lot of political radicalization happened after the event of the Rising. But what was under the event?

I was really interested in exploring the women’s movement in the rebellion and why people become radicalized. That’s at the core of Wild Sky. Here’s a woman Josie who has no access to education. She meets a schoolteacher who is politically involved politically. It’s at a time in Ireland when you know the Gaelic League, cultural revolution, the foot was slightly off the pedal for the priests and the usual policing instruments of that society. She gets to go set dancing on a Sunday and gets to meet people she would never normally meet. When they talked about the Women’s League and emancipation Josie didn’t even know what those words meant but they were words she never heard before. All Josie knew was her mother had a say in nothing. She was not willing to let that be her life. That’s how she became radicalized.

Pamela: The violence in the play is often represented by a choreographed physical expression of wild circular cartwheeling movement that looks almost against the will of the character. Where did that come from?

Deirdre: That’s director Jo Mangan—they found that in rehearsal very early on. I loved it. I had the notion of music all the time and it’s so much a part of that story. It was there from the conception for me. Wild Sky was very consciously not written about Padraig Pearse or Thomas McDonagh or any of “the boys” (male revolutionary commanders). I kept thinking about women, I kept thinking about Constance Markievicz. George Bernard Shaw described her as a cartwheel of irresponsibility. Women were always either mad or virgins. There was no in between.

Pamela: And in Wild Sky idiom is slightly period and very lyrical at times.

Deirdre: It was hard to find the voice. Then I remembered looking at my Dad who was born in 1929 and thinking of my mother who was born in 1933 and all my aunties. I knew and loved them very much. I kept thinking of their voices because they were only twelve years later. My grannies and grandads died when I was very young but I still have an echo of their voices in my head. Wild Sky was a great one for me because it made me realize I can write in history. Now I have two other big ambitious plays. One that is set in Leningrad in the second world war, and one that is set in Dublin in the 1930s about Ettie Steinberg, the only Irish citizen to have died in the Holocaust. I feel very comfortable there now as a result of Wild Sky.

Pamela: It’s great to hear about more plays coming and your expanding practice. I look forward to many more!

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

A very inspirational piece. For someone who has just completed a second draft of a new work, you both put some fire in my belly..

As a very political - and lyrical - playwright in Australia, where I too have great difficulty in breaking in to the established theatre scene, it is a joy to read of Deidre's determination, and success. Thank you both.

Your welcome it's lovely to hear some feedback from another female playwright! Good luck with your plays.