The Way Back Home

“If you know the beginning well, the end will not trouble you” —African Proverb

To write about the vitality and agency of the state of black theatre is quite a task because I find no urgency in many of these debates. To me the state of black theatre today is the same as it has ever been, ebbing and flowing, surging and retreating. It continues to be dressed up and down, applauded, revered, debated and reviled like everything else. Unfortunately, today black theatre has become synonymous with a genre and not a culture, which in my opinion is supremely dangerous. This shift is the root of why today African American voices and creativity are being co-opted, compromised, and commercialized. Let us not be fooled or distracted by all of the accolades and undeniable success that only an handful of black playwrights are currently enjoying because these celebratory accomplishments were designed to rape our community of the feeling of urgency that is needed to affect change. I fear we have begun to sell not only ourselves, but also our culture to the highest bidder thereby limiting our possibilities of growth.

Our Culture with a capital C is best incubated, crafted, and curated when nurtured in safe spaces that don’t look to define the black experience or lifestyle but instead celebrate it’s menagerie of shades and complexity; spaces that seek to acknowledge the authentic truth of who we are as a people. These spaces are our black cultural art institutions. Bricks and mortar, the owning and operating of these institutions are the key to the vitality and longevity of black theatre. Black arts institutions provide the most viable platform for us to display honest interpretations of the full spectrum of black life without censorship or commercialization. Let me put it to you this way—if you are a person without a home, no matter how many people allow you to stay for varied limited lengths of time, in various zip codes, from the most exclusive to the most basic of couches, are you not still homeless?

Home is a concept that is often taken for granted in this ongoing debate about the state of black theatre. We have unwittingly created an ecosystem of refugee artists—left to fend for themselves and cleave to whatever opportunity comes their way. The only way to really address these issues is to examine their roots. Are we seeking out or supporting the safe havens and spaces where we can express ourselves freely and fearlessly? The danger in making these discourses singularly about black theatre and not institution building is that the more black playwrights that get produced on Broadway or in other commercial venues—venues that might not care even a little bit about our culture and who we are as a people—the more the collective consensus is that there may no longer be a need for black cultural art institutions. As a result our institutions are on the brink of extinction and the expression of a richly complex beautiful culture is officially becoming an endangered species. And you, my refugee artist geniuses with your craft are left wandering.

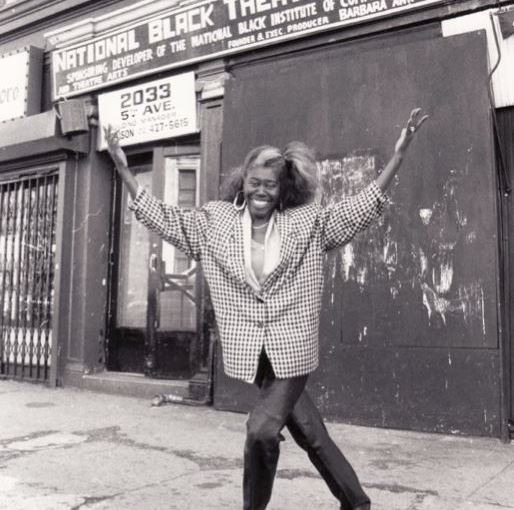

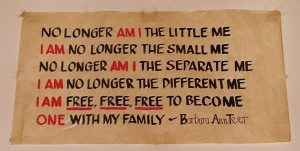

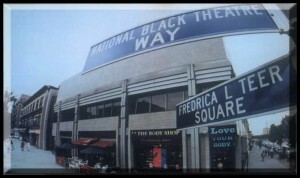

When my mother Dr. Barbara Ann Teer founded the National Black Theater (NBT) in 1968 she did it out of this very concern. She knew the key to her people’s liberation was through being able to tell authentic stories from an African perspective and in order to do that with unrelenting honesty & integrity they needed a space to call home. She moved up to Harlem and eventually bought the corner of 125th street & Fifth Avenue and built NBT—the first revenue generating Black Theater Arts complex in the country. That very same year Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would deliver his very last speech hours before being shot dead while pleading to his people to support and help strengthen our black institutions and culture. The growing recognition of the importance of having and supporting our own gave birth to the Black Arts Movement and the celebration of black consciousness, all of which marked an extremely fertile time in black culture and creativity.

We are all the custodians of what she and a long list of ancestors gave their lives for. We are all the beneficiaries of so many giant lives lived and dreams that shall not be deferred!

Unlike the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Arts Movement wasn’t solely focused on the artist, but rather the building of institutions. It was an imperative call to action that couldn’t be ignored. In the roughly ten-year span of the Black Arts Movement in New York alone (1965-1975), over two hundred black theatres emerged; today there are less than ten. I am well aware that the point I’m trying to make has another equally impassioned side that is also the key to black theatre growing and flourishing. As a young person and the CEO of NBT, I feel and see the frustrations that young artists have with black institutions. Oftentimes, artists feel like there is no room for their voices and experiences to be heard or valued—that there has been no place set at the table for them. So they get disillusioned and begin to build something new to call their own. As a founding member of The Coalition of Theaters of Color (Founding theaters include: Billie Holiday Theatre; Black Spectrum Theatre; H.A.D.L.E.Y. Players; National Black Theatre; Negro Ensemble Company; New Federal Theatre; New Heritage Theatre; Paul Robeson Theatre), I am constantly pushing my fellow institutions from within to embrace the incredibly exciting and fertile new movement that is happening in theater today. And things are changing.

At NBT our focus is on creating bridges between old and new paradigms, on articulating a lexicon between Dr. Teer’s generation and the generations to come. As a result, NBT has produced more new black playwrights and women playwrights in my time as CEO than any other black theatre in New York City. Because of this, our mission remains, our legacy grows, and the diversity of our stories is reflected in our diversity of audience. So where do we go from here? The first stop on this journey must be to reclaim what’s ours! Black theatre, black actors, black experiences, expression, and stories all live and die through the support of our black institutions and until people see the two as inextricably linked, black theatre remains in danger. It is essential that we begin to understand as a collective that the use of the word theatre on its own is limiting and marginalizing if not used merely as a point of departure. Second we all have a role to play nurturing our institutions. Seek them out if you are unfamiliar, bang on their doors until they let you in, never take no for an answer, donate, volunteer, and spread the word. This journey is not the sole responsibility of the institution.

When my mother passed in 2008 I didn’t have a choice but to come and pick up the baton of NBT. It was my responsibility, not as Dr. Teer’s daughter, but rather as a lover of my people and our craft. My “inheritance” was not mine at all—it is all of ours. We are all the custodians of what she and a long list of ancestors gave their lives for. We are all the beneficiaries of so many giant lives lived and dreams that shall not be deferred!

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here