Theatre History Podcast # 27

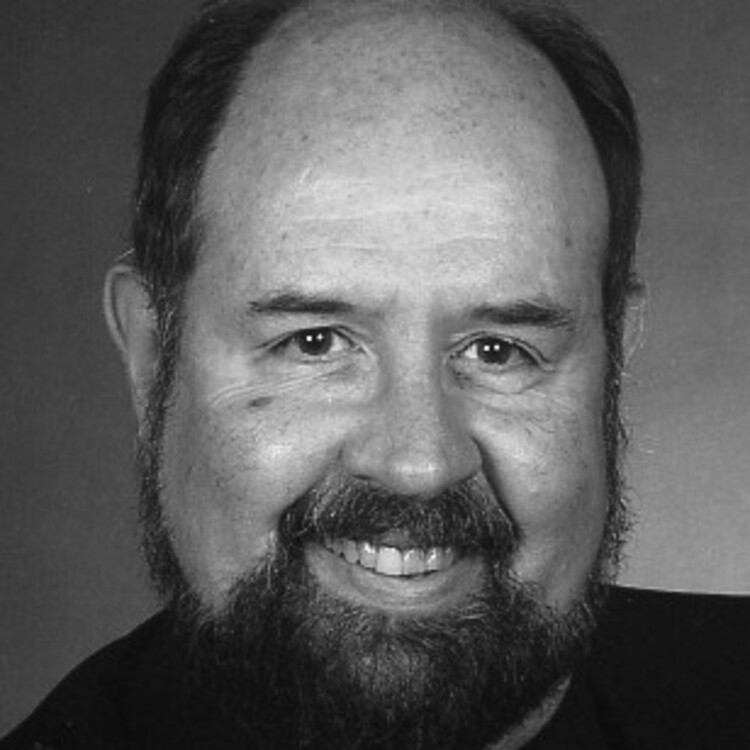

Learning About Ta’ziyeh with Dr. William O. Beeman

Long before Western-style theatre came to what is now Iran, a unique performance tradition had already developed that fused song, movement, and religion. Known as “ta’ziyeh,” it has since spread among Shiite communities in Iraq and Lebanon, as well as even farther afield. William O. Beeman, chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota, introduces us to the fascinating world of ta’ziyeh in this episode.

1947. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Links:

- Read more on ta’ziyeh in this essay by Dr. Peter Chelkowski.

- For more information on ta’ziyeh and other Iranian performance traditions, read Dr. Beeman’s book on Iranian Performance Traditions and Dr. Willem Floor’s History of Theater in Iran.

- Information on The Troupe, a 2004 documentary by Rabeah Ghaffari, on a production at Lincoln Center that was directed by renowned ta’ziyeh artist Mohammad B. Ghaffari.

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

Transcript

Michael Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a knowledge commons by and for the theatre community. It's available on iTunes and HowlRound.com.

Hi. Welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Mike Lueger. Many surveys of world theatre tend to dismiss the Middle East or even skip over it entirely. However, there are many vibrant and fascinating performance traditions in the region, including ta'zieh, a combination of theatre and ritual that's common in Iran. Here to tell us more is Dr. William O. Beeman. He's the chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota and the author of Iranian Performance Traditions. Bill, thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. William Beeman: You are most welcome. I'm delighted to be here and I hope that your audience will find this interesting.

Michael: Can we just begin with the basics? What is ta'zieh? Where is it performed? Where does it come from?

William: Ta'zieh is an indigenous theatre form that originated in Iran, and we know that it was active probably in the late seventeenth century. It predates any western theatre tradition in the Middle East, and so we know that it arose as an entirely indigenous form, that has a very original structure and a very original set of performance conventions, so occasionally people have said that, well, ta'zieh must be the result of the western dramatic traditions coming in to Iran, but actually, as I say, it's 100 to 150 years earlier and probably earlier than that, but we just don't have documentation for earlier ta'zieh performances. We know at least 250 attributed ta'zieh performance pieces. They've been collected by an Italian ambassador to Iran who was fascinated by this, named Cherulli, and they are now reposited in the Vatican library. Other ta'zieh scripts are scattered all around Iran and exist with troops that are existing throughout the country, so it is really a very, very fascinating form.

One of the hallmarks of ta'zieh today is that it has gravitated toward commemoration of the death of Imam Hussein, who was the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, who is martyred in the town of Karbala, in present-day Iraq. There's a long history about the split between Shia and Sunni populations, but the death of Imam Hussein, who was a Shia adherent, is the central mythical—and I don't use that term to indicate that something didn't happen, but it has been mythologized, but it's a central event in Shia Islam, and so sometimes ta'zieh has been called a passion drama. That's probably inaccurate, because if we take a look at all of the ta'zieh scripts that have been found, we find that they encompass a whole variety of theatrical material, from comic material to highly dramatic material, but the thing that has sustained it over many, many years has been this depiction of the religious drama of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein.

Michael: What would we see and hear at a ta'zieh performance? How would it be maybe familiar to western theatre-goers? How would it be very, very different?

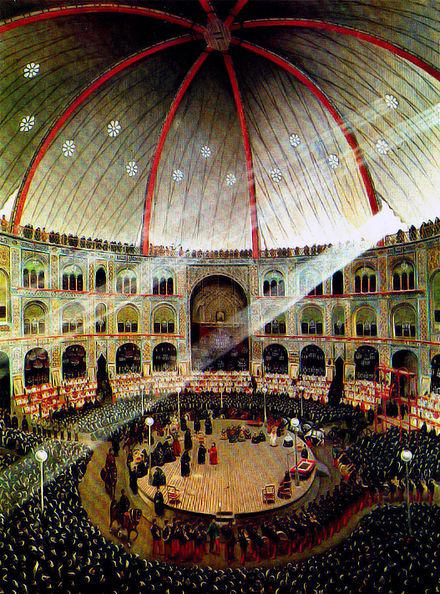

William: Ta'zieh takes place in an arena, and that's one of its most important features. In Iran, there are many venues that ta'zieh can be performed in, but one of the most common ones is in a building that is erected in many villages and towns, that really is specifically for the performance of this dramatic form, and this is called a Husseinyeh, and the Husseinyeh obviously recurs to Hussein, to Imam Hussein. It is oftentimes a very large—you might think of it as a very, very large black box theatre. Oftentimes, it's two or three stories high with an open arena in the middle, and this allows for the construction of a really, really big spectacle. In the most elaborate performances of ta'zieh, you not only have performers, but you also have animals, and the animals circulate in the performance. It's one of the very few performance forms where actors and vocalists actually have to perform on horseback, which they oftentimes have to do.

If the town or the village doesn't have a Husseinyeh, it doesn't have one of these buildings, you can still perform ta'zieh in an open-air space where the audience is completely surrounding the performance. There are a number of performance conventions that are very interesting. First of all, because the performance these days is centered so heavily on the story of Imam Hussein, you have a division by convention between the family of Imam Hussein and his supporters and the people who are oppressing him and eventually they kill him. They eventually murder him and all the male members of his family. So, the family of Imam Hussein is usually dressed in green, or if they're females, they're dressed in black, and males play female roles in this performance.

The Sunni opponents of Imam Hussein are dressed in red, so there's a color symbolism, a direct color symbolism, a red/green symbolism. The family of Imam Hussein actually chant or sing their lines, and the villains in this case will declaim their lines. So, you hear declamation on the part of the oppressors and you have singing and chanting on the part of the good people, the family of Imam Hussein. So, those are some very important conventions, and there's some additional ones, of when a person is traveling in a circle or in an arc in the performing area, that means they're going a long distance. So, for instance, the distance between Mecca and the city of Karbala. If they travel in straight lines, that means they're going a short distance, so that's an important convention of the dramatic form.

There's also instruments, and they usually consist of a bugle or a trumpet and drums. Those are the primary instruments that are traditionally used, and they serve as transitions between the various scenes, and what is also interesting is that the instruments alternate with the voice, especially the voice of Imam Hussein and his followers. So, you'll get a little musical interlude and then the performers will chant or sing. So, those are things that anybody who is watching ta'zieh would see.

There is, and there was, a very famous performance of ta'zieh that took place in 2002 as part of the Lincoln Center Festival, and that was done in a park in back of Lincoln Center. They erected a very large-essentially a circus tent for the performance, and so people who saw it at Lincoln Center were actually viewing a ta'zieh performance in a very authentic way. The director of that was Mohammad Ghaffari who actually still lives in New York, and I would say is the premier director of ta'zieh today.

Michael: Speaking of the people behind ta'zieh, the ones who perform and direct it, what does it take to become one of these performers? You mentioned horses, so I got to imagine there's some special skills that we might not normally think of in western actor training.

William: Well, first of all, most ta'zieh performers have been performing since they were children. The ta'zieh performance tends to run in families or it tends to run in communities. Because there are actual children in the story of Imam Hussein, and in some of the other ta'zieh performances as well, you need actual children to perform, and so we have children as young as six, seven, eight years old, who have started to perform when they're very, very, very young, and as they grow up, they gradually move into the adult roles. As one of our ta'zieh performers said, "When you reach puberty, your voice changes and you're a guy, then comes the moment of truth. Either you're going to be an Imam Hussein or someone in Imam Hussein's family because you can actually do the vocal stuff, or you're going to be one of the villains because you can't sing as well, and so you end up declaiming your lines."

But the ones who are declaiming, they also have very, very powerful voices, so voice training is a really important of what they do. The performances are stylized and there's a lot of swordplay and a lot of handling of weapons and other material things, so a performer really does have to know how to handle a lot of equipment on stage and handle it in a very elegant way because of the stylized nature of the performance.

Now, when I was in involved in the production of the performance at Lincoln Center, Mr. Ghaffari had his performers working for a month on all kinds of exercises for the breath, to sustain their energy on stage, 'cause they really do; it's really very athletic, and so he wanted to make sure that they had the stamina to be able to actually carry out the performance. He used traditional Iranian athletic exercises that come from the so-called House of Strength, the Zurkhaneh, that's used to train- in ancient times, used to train soldiers and in present day time serves as kind of an athletic club and so people are still training in the Zurkhaneh.

One of the things that you have to be able to do in ta'zieh is to spin, and spinning is an art, to be able to actually sustain spinning for—this is not spinning on bicycles, this is actually turning in a circle very rapidly, so that becomes a very important part of the exercises. So, voice training and athletic training are very important for the ta'zieh performers and, if you're going to play one of the major roles, you better know how to ride a horse. So, that's a skill that almost any person in a village would be able to train doing, but in modern days it may require some special training in order to be able to handle the horse.

There are other animals, too. Oftentimes when you get really elaborate performances, there are going to be camels, there are going to be sheep, and so these also have to be handled by someone who is dealing with those in the performance situation.

Michael: One last question about the performance aspect of ta'zieh. In many cases, if you're watching a performance, you're gonna see some of the performers, if not all of them, holding scripts. Is that correct?

William: That's correct, and there's a reason for it. In very conservative Islamic circles, the depiction of living humans is considered to be blasphemous, because you are creating an alternate reality to the reality of God, and so the ta'zieh performers had got into the convention some time ago, centuries ago, of actually taking their...they aren't scripts, they're actually sides in the Shakespearean sense. That is their own part, and they will hold the sides in their hand. They don't need them. They have their parts totally memorized, but they are holding the sides in their hand and they'll look at them from time to time and that is a way of placating their religious authorities that say you're somehow creating a creature or creating an individual that didn't exist or that God didn't create, but you're creating it.

Also, you're depicting individuals who are really quite sacred in Islam, like Imam Hussein, and in this situation, the performers will say, "No, we're not doing that. What we're doing is reciting a story and that's okay, and we just happen to be in costume and we just happen to be moving around and we happen to be chanting and we happen to be- that's to make the story better and so here are our scripts, so you can see that we're not creating anything, we're just reading the story."

So, it's a bit of sophistry, but for centuries it's placated the most conservative religions, who find that this might be questionable.

Michael: Speaking of how people view what's actually being performed there, there's a really interesting dynamic between the ta'zieh performers and the audience that's watching them. How is it supposed to affect its audience?

William: Well, ta'zieh means literally mourning, and there are other terms that have been used for ta'zieh in the past, one is Shab-e . Shab-e means simulation, but ta'zieh is, as I say, the Arabic word really means mourning, and the reason that people will give for their performance of ta'zieh is to encourage the audience to mourn the death of Imam Hussein, and by doing this, the audience is encouraged to weep and to mourn along with the people on stage, and over the years, this has become a real convention, that audiences go expecting to be deeply moved by these performances and to weep and to mourn in the audience itself. So, ta'zieh is something that enhances people's sense of the tragedy of Imam Hussein and his family and, for that reason, they are really very deeply moved.

The audience reaction, there are, as I say, a very few...We have in the past, in recent history, we have produced some comic ta'ziehs as well. People are encouraged to laugh, but in the end, it is really the mourning for Imam Hussein that is the reason in communities for this performance to actually go forward and be supported.

Michael: Now, we've been talking about how this been around, ta'zieh has been around in some form or another, for centuries. It's by no means a static, fixed form, but one of the things that I found interesting in some of the scholarly articles that you've produced about this is a certain unease with some more melodramatic acting styles that's maybe more associated with modern film or theatre. How does ta'zieh relate to "modern" performance forms, things like film or popular commercial theatre, and in a possibly related question, how does it relate, if at all, to contemporary events?

William: Well, first of all, there's no question that acting styles in modern film and television have definitely affected what contemporary performance of ta'zieh are doing, and it is a...Mr. Ghaffari is very adamant about this, and actually others as well, that ta'zieh as a performance form has this highly stylized quality, which in fact is deeply affecting. You don't really need the characters, Imam Hussein and other characters don't need to really be bathetic and over the top in producing their acting style, in order to be affecting. The very simple and very direct kinds of actions and speech are really enough to produce the dramatic effect that they're looking for.

So, the vulgarization, as Mr. Ghaffari would say, of ta'zieh is unnecessary, and that's one of the reasons why, especially in the Lincoln Center performances, he was very careful to try to curtail any attempt to try to go into some kind of realistic...a film portrayal. So, it really is probably inevitable that as western theatre and western theatre forms and film forms have been appropriated in Iran, that there's going to be some kind of cross-fertilization in that material, but for those who really know what ta'zieh is, it is a shame to see that happening.

Also, in present day, people have taken to using microphones and if the performers are correctly trained vocally, there's no need for microphones at all. It's the same as with western opera. Opera performers never use microphones and it's because they have the proper vocal training that will allow their voices to carry in 4,000-seat theatre. So, the idea that Imam Hussein would be carrying around a microphone and declaiming into the microphone is rather unnecessary and rather silly, but as you know, amplified voices have become common in theatre, even in western theatre, even in very small houses, so we mourn the fact that actors are not getting proper vocal training, even here in the United States.

In films, you don't use the same kind of declamatory vocal style that you would use on the stage, but film and television have so dominated our own performance traditions, that people are unable to project from the stage in many cases. So, this is, as I say, this is an unfortunate situation.

Yeah, the story of Imam Hussein, if you know it, is in fact a very simple story of good and evil. There are the very good, righteous sincere characters who embody the truth, and then there are the evil characters who are trying to exercise power and to essentially suppress the truthful, sincere people. So, this is inherently political, and this is one of the reasons why ta'zieh has been problematic for governments in Iran and also in the other places where it's performed. It's performed in Shia communities in Iraq and in Lebanon, to some degree in Afghanistan, and in slightly different forms, even in Shia communities in India. It's also been performed in Bahrain.

So, in places where ta'zieh has been performed with this general message of good versus evil, the idea that the evil people might be associated, for instance, with the oppressive governments, very hard to avoid, and so for that reason...You don't need to explicitly identify the bad characters with an oppressive government or an oppressive ruler, the population gets that. It's really easy for them to see it, but since in Iran and other countries in the Middle East, people are quite used to expressing political views through metaphorical expression, particularly poetry. But, as I say, they can't be blamed for being subversive, but at the same time, the message is and can be subversive in a situation where people themselves feel oppressed by a governmental situation.

So, over the years, in Iran, both during the period of the Shah and before the revolution of 1978 and 1979, and in the current Islamic Republic, there have been attempts to try to shut down ta'zieh performances because they might be interpreted as being too political, but because they are based, these days, primarily in a religious expression, it's really impossible to do because people claim that they're what they're doing is not political, it's in fact religious, and so the authorities are really caught in a situation where they can't really, really suppress it, even though they're uncomfortable with it in many cases.

Michael: Now, for anyone listening to wants to find out more about ta'zieh, what would you recommend? What can they search out to learn and experience more about this performance tradition?

William: Well, you have mentioned a recent book that I've written on Iranian performance traditions and I, of course, would love to have people purchase and read that book. It deals not only with ta'zieh, but also with other traditional performance forms in Iran. But in the 1970s, the great Peter Chelkowski, who was one of the great authorities on ta'zieh, he's now retired, but we published a book from New York University Press that was the result of a symposium, an international symposium on ta'zieh with many, many excellent articles. So, that's still an authoritative text for any of us.

There are many writings in Persian, but I'm not sure that all members of your audience would actually be able to access them or read them. In shameless self-promotion, I would suggest that people read my book. Also, there is a—and I'm sorry, I just don't remember the title, my colleague William Floor, F-L-O-O-R, has also written a wonderful book on the history of Iranian theatre, and he has a lot of material in that, including some vintage photographs that I think people would very much enjoy.

Michael: We'll post some links to information about Dr. Beeman's work on ta'zieh and other performance traditions from Iran. I will post those in the show notes. Bill, thank you so much for a great conversation.

William: You're most welcome. I'm so glad that you had this interest in ta'zieh and I think that the more that people in western theatre traditions can become informed about ta'zieh, the more I think our idea about what's possible in theatre will be enriched.

Michael: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit HowlRound.com and follow HowlRound and @theatrehistory on Twitter. A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound who make this show possible. Our theme music is The Black Crook Gallop, which comes to us courtesy of the New York Public Library Libretto Project, and Adam Roberts. Thanks as well to Tim Cross, who designed our logo, and finally thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here