What Sort of Bridge Will You Build?

As the Native director I hold in the highest esteem working on the American stage today, I asked Madeline Sayet to offer her perspective. Her understanding and integrity of her own identity—despite the world's attempt to deconstruct, question, or triviliaze it—opens the door to what she calls a “bridge of understanding.”—Mary Kathryn Nagle, series curator

“What would the Old World historic shrines and scenes be without their traditions and classical associations? And what would the New World scenes be without their human traditions recited as the ancients knew them to lift our imaginations above the land and sea into the clouds? But, where are the spokesmen for the age of legend for the natives?” —Dr. Gladys Tantaquidgeon, Mohegan Medicine Woman and Anthropologist (1899-2005)

I was raised on the stories that shaped Connecticut before pale strangers ever came to its shores. Would you like to hear them? The stories of the land you are standing on right now? Breathe in what’s around you. The way the woods come alive to you as a child the first time you find out about faeries? Buried in the northeast woodlands, we have our own little people and more stories than you would think possible . . . but no one is listening.

Do you remember dressing up as an Indian for Thanksgiving in elementary school? Learning how to make a fake headdress out of construction paper? That is how early we are taught that redface is acceptable. Appropriation is part of Americana.

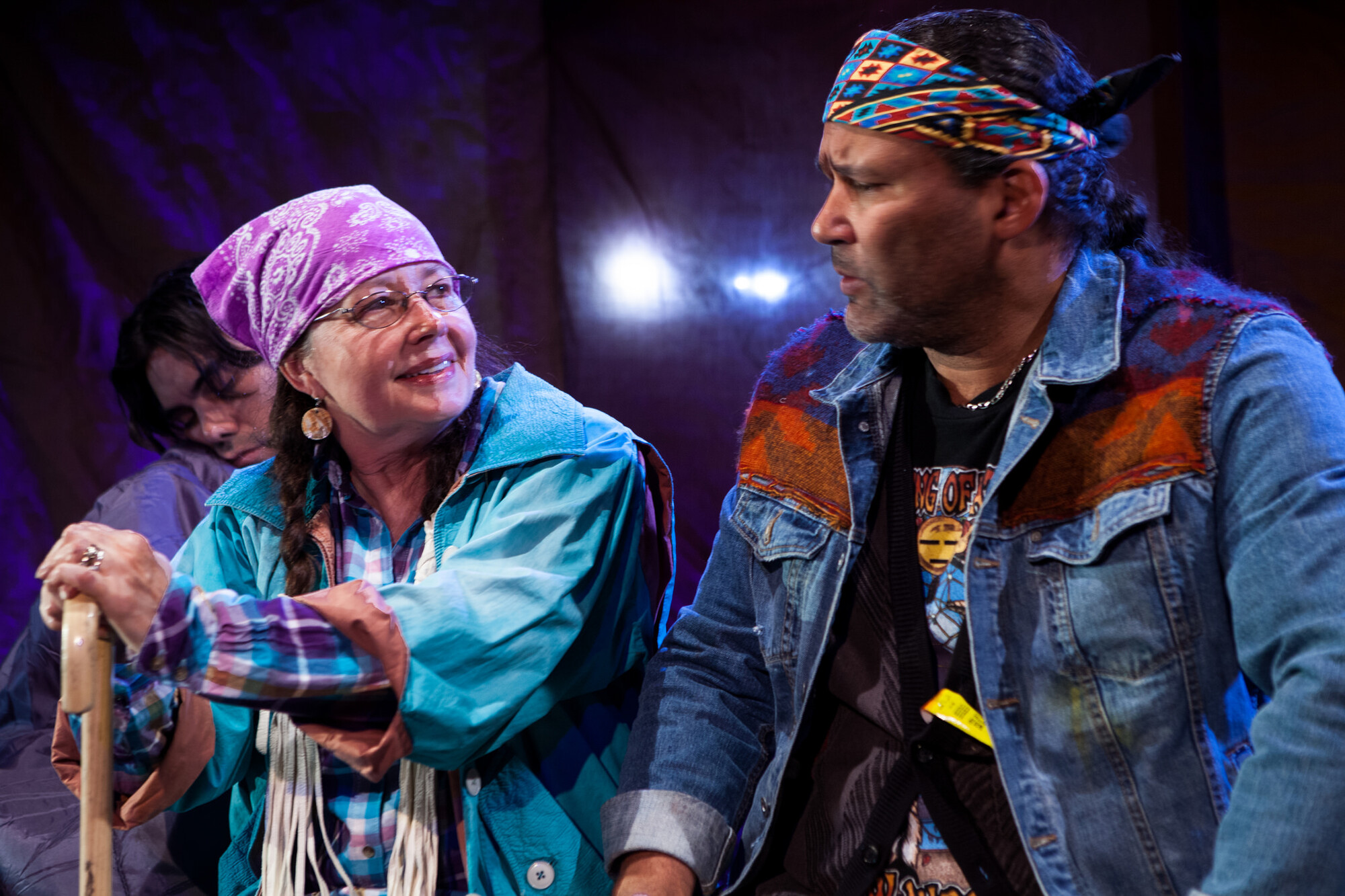

Native American theatre artists are the most underserved constituency. Not hiring Native theatre artists ignores the entire wealth of perspectives and storytelling traditions that are rooted in the soil beneath our feet. Hiring Native actors, playwrights, and directors to tell Native stories is vital. But, only hiring Native Artists for Native-specific projects denies them their complex humanity and inclusion in the world.

People are not born actors. They become them. Make space for them, invite them, and they will be there. But if there is no work and they are repeatedly told that they do not belong in the theatre, you will be responsible for creating an environment of hopelessness for Native artists, and telling the world that those voices do not matter.

Currently, at Amerinda (American Indian Artists) Inc., I am founding a Native American Shakespeare ensemble.

Over and over and over again I have been asked: “But why Shakespeare? I don’t see why Native artists should be doing Shakespeare.”

I have concocted a number of well articulated, complex responses to field ignorance and obey grant proposals—but the other day, someone finally pinpointed the problem with the question itself.

“Wait, so you are saying, your company of actors wants to perform Shakespeare?”

“Yes.”

“Shouldn’t that be reason enough?”

“Yes. Yes, it should be.”

Why do we have to explain doing what the majority of American theatres do without fear? Why must it be a white world or a Native world?

I was not born a director. It happened because of Caliban, in The Tempest. A Shakespeare junkie since childhood, I couldn’t understand why the western world saw Caliban as a monster when he was an indigenous hero.

So I became a director, to connect the dots, build a bridge, to show others what I saw. Help people understand.

This summer, I am directing The Magic Flute at the Glimmerglass Festival and Amerinda’s Shakespeare in the NYC parks. That’s right. Mozart and Shakespeare. I always bring myself and my culture to my work, but you know what? Spoiler alert: You won’t see buckskin and feathers in either production.

Native actors, like most actors, want a shot at playing Macbeth. As an individual Native artist, I bring something new to Mozart. It shouldn’t be a political act for me to do so.

We should not be forced to check boxes and confine ourselves to them in a creative industry. It should be about the work.

I recently wrote a blog post about my frustration with the role of a “director” in the traditional western masculine sense. Barking orders like a drill sergeant has never really been my style. So, I asked Mohegan Elder Stephanie Fielding, what the Mohegan word for my job would be. And she responded “Kutayun Uyasunaquock.”

The most accurate translation is: “Our Heart She Leads Us There.”

In my language, my role is a job I fulfill proudly. Who I am. Where I come from. Ideas can get lost in translation. This leadership structure exists in the world, not to be ignored, but for everyone to benefit from. Too many women are frustrated with the western patriarchal leadership model to not be offered other frameworks. There are many across the globe that honor femininity, instead of condescend toward it.

When I go into an interview, I am commonly greeted with, “Oh, you don’t look Native.” And I ask myself, “How many times do I want to put myself in an environment where who I am is being attacked, due to reductive expectations and essentializations of what I should be? What are those expectations based on? What exactly do you want me to look like?”

If there is never anyone Native in positions of power in the theatre, how will Native theatre artists ever feel safe there?

How can a child see a future for himself, if he is never depicted onstage in an empowering way?

I’ve heard the excuse—that there are no Native theatre artists.

That simply is not true.

People are not born actors. They become them. Make space for them, invite them, and they will be there. But if there is no work and they are repeatedly told that they do not belong in the theatre, you will be responsible for creating an environment of hopelessness for Native artists, and telling the world that those voices do not matter.

As a kid, I was fascinated by the parallels between stories. Like a bridge between worlds. Ways that unique perspectives can create a sense of oneness between many peoples. Maybe I am chasing a bridge going nowhere. But every project I work on, I see progress. We are not a sideshow. Now is the time for Native artists to be included everywhere.

In 1931, when my family built the oldest Indian-owned and operated museum in America, it was founded with the idea that “It’s hard to hate someone you know a lot about.” My great aunts and uncles carried our stories to the community and by the time I entered the world, all of my school teachers had visited the museum as children, and not only knew about the Mohegan people, but had loving memories of time spent at the museum with my family. Stories have power.

As children, we crave bedtime stories to keep the night terrors away. Story is and has always traditionally been used as medicine. From the tales passed down from grandmas and aunties to the modern need to binge on Netflix.

That is our power as theatre artists. To mold and shape the narrative. To decide what happens when a script is opened up and characters are led out and into the world. So, what sort of bridge will you build for them?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here