Christin Eve Cato is a playwright, dramaturg, and performing artist from the Bronx. She is affiliated with New York City theater companies WP Theatre (Playwrights Lab); Pregones/PRTT (ensemble member & former resident dramaturg), INTAR Theatre (UNIT 52 ensemble member), and the Latinx Playwrights Circle. Cato's artistic style is expressed through Caribbean culture and the Afro-Latinx diaspora, honoring her Puerto Rican and Jamaican roots. Jorge Piña’s career as a Chicano theatre artist spans over forty years and includes working as an artistic director, managing producer, street theatre actor, curator, and grants writer. Early in his career, he toured extensively throughout United State, Mexico, and Cuba—from prisons and labor camps to Universities and International Theatre Festivals. He now serves as the director of programs at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center. Their conversation focuses on community engagement, the importance of caring for our elders, and their advice for future generations to be able to sustain this work while caring for themselves and each other.

Can’t Do Theatre by Yourself

Jorge Piña and the cast and crew of Petra’s Pecado by Rupert Reyes at the first reading of Petra’s Pecado at the Historic Guadalupe Theater. Directed by Rodney Garza. Scenic design by Roland Mazuca. Costume design by Kim Corbin. Lighting design by Max Parrilla. Videographer James Borrego. Technical Director Jorge Luis Gamboa. Production stage manager Mark Gonzales. Photo by Hector Garza.

Christin Eve Cato: How are you?

Jorge Piña: Dormido. It was eighty degrees yesterday and this morning was thirty-eight.

Christin: Wow.

Jorge: Welcome to Texas weather.

Christin: Where in Texas?

Jorge: San Antonio.

Christin: Where were you born?

Jorge: Not far from here, Del Rio. It’s a border city next to Acuña, Coahuila, Mexico. As a little boy, I was very fortunate to grow up in three energies: San Antonio, city; Del Rio, small town; and then in Mexico in the ranchos in Mexico with my curandera grandmother. And we would spend the summers there with my cousins, helping out the rancho. Soon as the summer came, we would all take off.

And my father being very resourceful there at the air base in Del Rio, he would raid the dumpsters. They would just throw all kinds of stuff out, and he would take all that stuff back to the rancho. Por que era gente pobre. When I was growing up, me and my little brother, we were the only ones with tennis shoes. Everybody was barefoot. So my mother would always bring shoes and clothing and that sort of thing, constantly, because there was... I mean, the poverty was heavy.

Christin: Wow. That sounds beautiful though. Your family really helped out a lot of people.

Jorge: Right. And that’s where I would learn a lot of my values, through my family. I really didn’t get into the arts until I was already in high school. What the rancho gave me was my imagination and also my identity. Over there, being cousins who spoke English, we were called pochos; and over here in United States, we were called mojados, wetbacks. So the movement is the one that gave me the identity as far as being a Chicano. And then it was the movement, the artists that were in the movement that gave me that door to open and get creative.

Christin: You’re talking about the Chicano movement?

Jorge: Mm-hmm. In my senior year at Memorial High School, I started the Chicano Club. Every week, I would invite folks from throughout the community to come talk to us and in the class.

There was a split between the Raza Unida Party and the Mexican American Democrats. The Mexican American Democrats were holding strong power. They didn’t want the Raza Unida because they felt they were too radical. So there was a split. And as a young man, I would constantly go to these meetings, and I saw these arguments, and nothing was being done. So there is where I would meet and see Teatro Campesino and Los Moscardones from Mexico. And it spoke to me. It called me. And that’s when I got started.

There was a new group forming called Chicano Arts Theatre here in San Antonio. They were going to have auditions. I showed up. I had seen a few high school plays. I had never gone to a theatre. I saw these performances, and I fell in love with it. So I started to tour with Chicano Arts Theatre. We would get together and write some notes or get some ideas, what the message was going to be. Little did we know that we were creating actos, short skits. And some of them were funny, some of them dramatic. Some of them were satirical, some of them were goofy, some of them we just, “Oh well, we tried.”

But in 1975, I saw my first El Teatro Nacional de Aztlán (TENAZ) Festival, and there’s where I got to see other groups, meet groups like Su Teatro from Denver and Teatro de la Esperanza.

It was the first time I got to see full-length plays. Before, it was all actos, little short scripts. Then I started to see that there was other areas.

Jorge Piña in front of the set for Petra’s Pecado by Rupert Reyes at the Historic Guadalupe Theater. Directed by Rodney Garza. Scenic design by Roland Mazuca. Costume design by Kim Corbin. Lighting design by Max Parrilla. Videographer James Borrego. Technical Director Jorge Luis Gamboa. Production stage manager Mark Gonzales. Photo by Hector Garza.

Christin: I love that. What was the first play that you saw that changed your life?

Jorge: The one that really sticks to my heart is La Victima.

Christin: You produced that, didn’t you?

Jorge: Many times.

Christin: You saw it first before you ever produced it.

Jorge: Right.

At the TENAZ festivals, there were workshops or platicas; that’s where I would get to meet other writers. And that’s when we started to learn about design: light design, costume design, et cetera. Eventually, there was a new theatre group starting in Houston. Arnold Mercado, a Puerto Rican, had landed a Community Engagement and Touring Artists (CETA) grant . He wanted to create a bilingual professional theatre in Houston.

I auditioned three times, and I finally got in. My father filled up my car with gasoline, gave me $80, and I took off to Houston. That was the first time I’d ever been to Houston, the first time I’d ever seen skyscrapers and smog at the same time. So there’s where I would learn about all these other writers from Mexico and Latin America, and also the theatre from Cuba and Puerto Rico and so on. And then I got to meet all these other folks. One of them became my wife, Ruby Nelda Perez. And there is where I would get to meet Emilio Carballido, and I became friends with him. He was in Houston. The university had brought him down, he had heard about us and came over. So we changed the name to Teatro Bilingue de Houston (TBH). We started the organization 1977, and we started doing teatro.

Ruby joined Teatro Esperanza in Santa Barbara, Calfornia in 1978. She auditioned, got a part, and started touring. They performed in Houston, and I fell in love with the group. So there was an opening. I joined. I was with Esperanza 1980 and 1981. And with them, we toured all over the United States, Mejico, Cuba...

Ruby had left. She came back to Houston to be the artistic director of Teatro Bilingue de Houston. So I stayed in California with the company. Eventually, I left Esperanza. I went back to Houston and started directing for TBH. And Ruby was the artistic director and executive director. Then, that’s when Esperanza called us, and they were organizing. I got to meet… before they were Pregones/PRTT, I think they were called Teatro Cuatro, I believe.

Christin: I’m an ensemble member with Pregones now.

Christin Eve Cato, playwright, on the set of Sancocho. Directed by Rebecca Martinez. Scenic design by Raul Abrego. Costume design by Harry Nadal. Lighting design by Maria-Cristina Fusté. Sound design by Germán Martinez. Props design by Addison Heeren. Portrait by Peter Bellamy.

Jorge: So that’s there’s where I would get to meet all these other groups from throughout Latin America and all these folks.

Christin: That’s amazing.

Jorge: By 1983 no money was coming in. I was looking for work. I heard that in San Antonio they were starting a new organization called the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, and they were looking for a theatre director.

Pedro Rodriguez, who just passed away recently, interviewed me. He was an amazing Chicano warrior, a former professor, and he ran the organization from ‘193 all the way to the late nineties. So he was my mentor. I started in January of 1984, the same week that Sandra Cisneros started. She ran the literature program, and I ran the theatre arts program. I remained at the Guadalupe until 2000.

There, I produced sixty productions and two TENAZ theatre festivals in 1988 and 1992. I also started Grupo Animo with a youth theatre company in 1992. I noticed that in the field, there wasn’t a lot of women playwrights or women directors. I started to hire more women writers, more women-issued plays, and women directors, and so on. So we were doing four plays a year, plus classes, plus presenting, and then Grupo Animo in the summer. That was my schedule for the last part of the nineties, and of course, we had very strong money in the nineties. It was a program called Gateways with monies from the Ford Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation.

Prior to that, as Chicano teatristas, we were taking the work to the people. Now we were asking the people to come to us.

Christin: This fund that you just mentioned, does it not exist anymore?

Jorge: No, the Gateways was just a project during that time. Eventually it faded off after I had left.

At my very first play, Los Desregados, we had ten people in the audience. And back then it was a four-hundred-seat house. And I said, “Oh lordy.” Prior to that, as Chicano teatristas, we were taking the work to the people. Now we were asking the people to come to us. So I changed gears.

Christin: What did you do?

Jorge: When Ford Foundation was knocking on our door, I said, “Well, I needed to develop an audience.” And so they took it and they started calling it audience development. Now everybody uses that term with their grants, but that’s what I started calling it back in 1984. You do not develop an audience from your desk; you have to go to where the people are at.

When I did Real Women Have Curves, and premiered it here, I’d go to the centers and to the factories and talk about the play. Some places, they would allow me to pass flyers, some would not. And I would also give free passes.

Christin: Do you think audience development—I love that the term was coined in the eighties and this is so great to learn—but how do you think the way we develop audiences has changed now?

Jorge: Audience development never ends. You have to change with technology. You have to constantly reinvent yourself. You have to constantly present yourself and realize that majority of these folks have never seen a play before. Once they see a show, once they get glued, you create the relationship; and it becomes personal.

So that’s what the Guadalupe was about. By 1988, all the plays started to get sold out. It took me four years before every show was sold out.

If you use today’s energy, creativity, and stubbornness, and anger—and understanding history—there’s where you get the formula to create your future and how to plant those seeds.

Christin: Wow.

Jorge: And so I had some failures and successes. My focus was to give opportunities to playwrights, to directors. It was always bringing artistic integrity to the stage, meaning if you have a very weak rehearsal, you’re going to have a weak production. So you have to put a lot of strength into your rehearsals.

Christin: Yes. I agree 100 percent. I mean, as an actor, the only way I feel prepared for production is if I know rehearsals were well delegated in the way that there was enough time spent on the scenes, enough time spent on the character development, enough time spent on blocking, enough time spent...

Jorge: Right. A good balance for the performer, for the technicians, for the front of house.

Christin: That too. Absolutely.

Jorge: And then when you have a hit, you have to have all these volunteers to help people sit down before the show starts and so forth.

Christin: Yeah, it’s definitely a collaborative effort. Can’t do theatre by yourself.

Jorge: No.

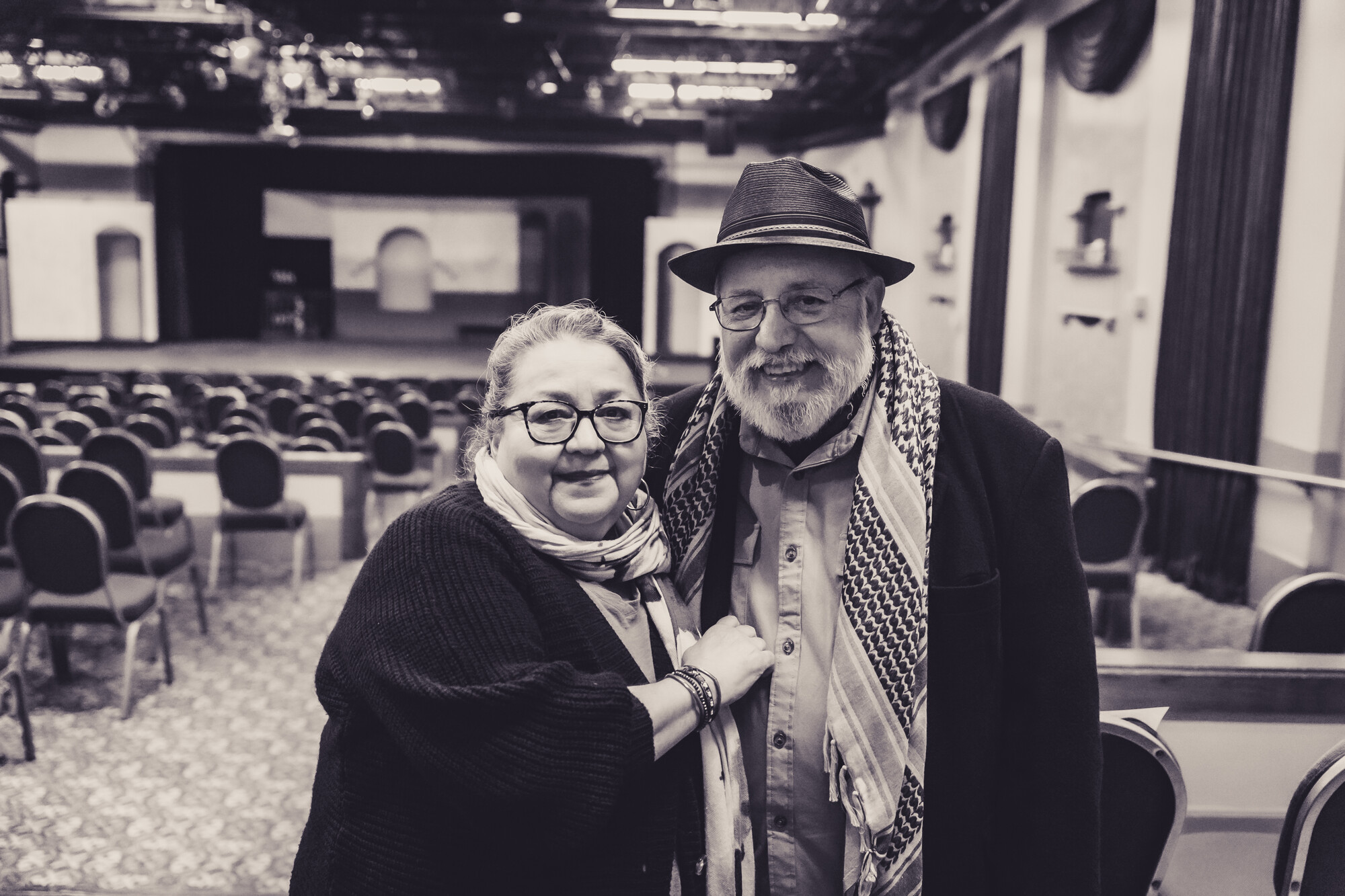

Jorge Piña with his wife, acclaimed Chican actor Ruby Nelda Perez, at the Historic Guadalupe Theater after a performance of Petra’s Pecado by Rupert Reyes. Directed by Rodney Garza. Scenic design by Roland Mazuca. Costume design by Kim Corbin. Lighting design by Max Parrilla. Videographer James Borrego. Technical Director Jorge Luis Gamboa. Production stage manager Mark Gonzales. Photo by Hector Garza.

Christin: This has been a great conversation. I really, really love what we did. This is history. We were talking history today.

What advice do you have for the next generation who is also passionate about the preservation and continued success of Latinx teatro?

Jorge: Remain stubborn. Remain stubborn to your creativity, to your art. Learn to listen and continue to be creative. Continue to engage. Continue to ask questions. Listen to your elders. Become a leader. Become a mentor. And always question what is happening today right now. Understand history: how did we get here and how can we change? Because I truly believe if you use today’s energy, creativity, and stubbornness, and anger—and understanding history—there’s where you get the formula to create your future and how to plant those seeds.

And sometimes, start over. Be creative. Don’t let depression take over. And if it does, be creative by getting out of there. Because we as artists, we abuse ourselves.

Christin: Trauma. There’s a lot of trauma and a lot of healing to be done.

We experience a lot of rejection. We experience, sometimes, financial issues. Rejection and financial issues is enough to send someone down a depression hole.

But what is political? Political is culture. Political is how we engage in our communities.

Jorge: Right. You have to knock on a door ten times. Get ready for it never to open.

Christin: Right.

Jorge: My philosophy is that now I have the door to open. Anybody knocks, I just say, “Come on in.” I always try to make time for everybody, and no matter what age. I’m seeing a lot of folks older, my age. That’s my next thinking is, what am I going to do for this generation, for this age?

Christin: That’s beautiful. I feel like we’re always focusing on what the next generation is, but the next generation always has to include the other generations, right? I think the goal is to learn how to work intergenerationally.

Jorge: As a teenager, I met Emma Tenayuca, Lydia Mendoza. Little did I know, I when produced a play about her years later, I would meet Willie Velazquez. Mind you, he was ten years older than me. So he was a mentor. I went out of my way to meet all these folks. Yes. That’s what helped me a lot when I was young.

So that’s why we get to meet a lot of carperos. Of course, one of the most famous peladitos was Cantinflas; but the peladitos would move the show in the carpa. So there was all these carpas on Guadalupe Street in the 1880s, and the last carpa closed the door in 1949. I was very fortunate to be in my youth to grab that energy and to pass it on with the teatro chicano. Each carpa was different, and you had this big split between the carpas and the people that performed in the theatres. The ones that performed in the theatres never performed in the carpas because that was like lowlife. It was a class thing.

Christin: Listening to this conversation, I’m learning about all these different groups that formed, about the movement, and about how politics has always been this segue way into art and vice versa… It’s like this relationship between politics and art. It’s a lot of that I find to be central to Latine theatre.

Even my own work as a playwright is so political. I wonder if that’s something we just have to accept. Is our art always just going to be political? But what is political? Political is culture. Political is how we engage in our communities. Political is how we show up in the world and what we believe in. Right?

Jorge: Right.

Christin: And I’m wondering if, because of the nature of, because of the nature of how we exist and how we’ve existed in this world, is our work always going to be political in some sense?

Jorge: I believe so because the struggle’s still here. As artists, I mean there’s a point where you create what you see and then you create what you feel.

Shirley Rumierk and Zuleyma Guevara in Sancocho by Christin Eve Cato at the WP Theater (Produced by WP Theater, the Latinx Playwrights Circle, and the Sol Project). Directed by Rebecca Martinez. Scenic design by Raul Abrego. Costume design by Harry Nadal. Lighting design by Maria-Cristina Fusté. Sound design by Germán Martinez. Props design by Addison Heeren. Photo by Joan Marcus.

Christin: Yeah. A whole book could be written about why our art is political and how the political aspect is included in all of these experiences.

What do you want people to remember you for?

Jorge: That I tried and that I gave opportunities. I created opportunities. And the struggle continues, so we need to continue to work it. That for me, this was a calling. I don’t have words.

Christin: Yeah. Sometimes we just want to be remembered for our hearts, you know, how we existed and how we showed up. Yeah. Well, I’ll definitely remember you for that.

Jorge: Gracias.

Christin: De nada.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here