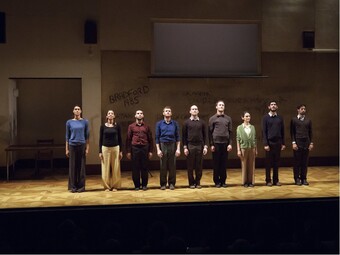

Despite the delectably divergent tones of Midsummer and Macbeth, there was something beyond their shared location that firmly united the two shows: an atmosphere of camaraderie and joy. Anyone who regularly attends theatre is probably familiar with the indefinable but palpable zest that actors who are truly enjoying themselves bring to the experience. A bond of genuine friendship and respect between castmates deepens the moments of danger in addition to the moments of levity: after all, it requires a certain amount of trust to put yourself in physically and emotionally vulnerable positions. It was clear throughout both performances that Mahoney and Wilkinson’s actors trusted each other and their directors implicitly. It was equally obvious that they were genuinely having an excellent time—and because of that, so did everyone in attendance.

Both of us came into the room trying to ask, “How can we completely throw away those power structures and build something that feels like there is no ego inside of it?”

In conversation with Mahoney and Wilkinson after the joint runs of Midsummer and Macbeth had ended, they explained that the curation of this dynamic was not only purposeful, but in fact one of their main objectives in founding Double Feature. Their approach hinged on establishing a non-hierarchical structure, one intended to foster a clear exchange of communication and place equal value on the needs and voices of all artists involved. “Directing comes with all of these assumptions about preset positions and power structures,” remarked Mahoney. “And both of us came into the room trying to ask, ‘How can we completely throw away those power structures and build something that feels like there is no ego inside of it?’”

Both directors emphasized that a lack of hierarchy is not equivalent to a lack of accountability. “You don't need a hierarchy for people to have responsibilities,” Wilkinson explained. “Mikhaela and I are really clear about what we put forward and what we expect back. Everybody knows their responsibilities, and it doesn't mean there has to be power attached to it.” Rather than being accountable to a single authority figure, each member of the group was accountable to the entire ensemble. “If you create a space where you are listening to everyone, then everyone also listens to each other,” said Mahoney.

Mahoney and Wilkinson were well aware that they were embarking on an experiment, and that their methods might be branded as idealistic by those accustomed to a more regimented chain of command. The pair approached this challenge with a grounded practicality. “It's not a utopia,” Mahoney shared candidly. “We're just doing our best. We don't have as many resources as we’d want to give people. And that can often feel like a barrier to even starting.” When moments of conflict did arise in the production process, they were indeed often related to a strain on their time, funds, and supplies. “In a moment where there are two people who need the same thing, and no one is more in charge than the other, how do you actually do that?” Wilkinson asked. “By having deep conversations, being really clear about what you need, and also being willing to, in that moment, think beyond yourself and put care forward.”

This emphasis on care extended beyond Mahoney and Wilkinson to encompass every person involved in the production. Each team member’s role and specific duties were laid out explicitly from the beginning of the process “so that people can have freedom inside of that structure,” according to Wilkinson. This not only helped to provide an organizational backbone, but allowed actors the flexibility to continue taking on other work to support themselves economically during rehearsals and performances. “The big thing I think that also builds community is transparency,” said Wilkinson. “When I was emailing actors, I was like, ‘This is how much I can pay you. I know that I can't pay you what you're worth. And we understand what your life is going to look like. We understand that you're going to maybe be working another job.’” Essentially, Mahoney and Wilkinson made every possible effort to make participation in Double Feature accessible for their actors and crew.

As Mahoney and Wilkinson discussed how they built the community that brought Midsummer and Macbeth to life, I couldn’t help but think of the many larger theatre companies that pay their artists much greater sums of money but offer the absolute minimum (and sometimes even less than that) in establishing a humane and happy space in which to work. Does there come a point at which a theatrical institution becomes too large to effectively function as a community? Or is it not a question of scale, but of consistent and care-driven communication? And, if practices like Double Feature’s were adopted, might these larger institutions be better able to avoid all-too-common acts of accidental mistreatment toward those involved in their productions?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I was so drawn to this article because my whole research life is about how Shakespeare connects to me as a queer person. I really resonate with a lot of what you say about how important the immersive feel of the piece was, how you were "actually connecting with Shakespeare’s work on a joyful, visceral level."

I feel like the goal is always "more pay, more resources, bigger company" and I appreciate what you bring up about the institutionalized nature of commercial theatre taking away from community, and how the community vibe of these shows is exactly what drew you in. Sad to have missed these shows!

Thank you, Rainer! The queerness and communal nature of Double Feature Plays was absolute my draw as well, and I'm glad that these reflections resonated with you. Hopefully we'll both have the chance to see more of Double Feature's work in the upcoming seasons!