Devising the New Avant-garde—Part 2

The Renaissance Kid and the Open Play

What is avant-garde theater today? It’s easy enough to look back on last year’s vanguard, but how can we define the movement we are in the midst of? In her series, Kate Kremer explores the question of the new avant-garde. This post is a continuation on the relationship between playwriting and devising, and is part of an ongoing blog series on the “new avant-garde.”

What began in the 1960s and ‘70s as an overthrow of the “hegemony of the playwright,” in Arnold Aronson’s terms, has ended in an increasingly democratic field of multi-taskers. Boundaries within theater and among the arts have blurred, with artists moving between writing, teaching, directing, performing, devising, filmmaking, dancing, storytelling, performance art—it’s what professor David Williams describes as the “multi-functional ‘artist maker’” and playwright and theater/filmmaker Will Arbery heralds as the “emergence of the new Renaissance kids.”

“I can conceive of a time soon when James Franco won’t seem so freaking freakish,” Arbery quips. “We’re becoming expert multi-taskers.” Indeed, filmmaker/artist/writer/performer Miranda July describes her effort to bring about just such a renaissance in a 2005 interview in BOMB Magazine:

I have a gigantic plan…it involves performance, and fiction, and radio, and the www, and TV and features that are both “conventional” and totally not. And when I am done with my plan…hopefully there will be a little more space for people living with profound doubt to tell their stories in all different mediums.

In making art that spans all available media, July advocates for a broader culture of expression and engagement, in which the act of art is not separate from life—a novel shelved, a play departed—but intimately, inseparably a part of it.

The rise of artistic multi-functionalism, and the open, assimilative, and collaborative values it implies, has coincided with the emergence of devising as a major theatrical discipline. Although devising is hardly new the process of developing work through collaboration among a group of artists has gained traction in recent years.

It makes sense: both multi-functionalism and devising are solutions to an economic downturn, ways to continue creating complex and multivalent art in a scale-back climate. The multifunctional artist works in many mediums partly as a way to keep working; likewise, the growing interest in devising may have something to do with what Sarah Ruhl describes as “the death of the ensemble.”

“Where did all the ensembles go,” Ruhl asks in her recently published book of essays, “and has there ever been a major writer who emerged from a theater culture not associated with an acting ensemble that evolved a style over time? Shakespeare had the King’s Men, Chekhov had the Moscow Art Theatre…Must we make new ensembles to evolve new ways of making theater for the present moment?” By “ensemble,” Ruhl presumably refers to the practice of maintaining a resident acting ensemble—and not to ensemble-based theater collectives like the Rude Mechs, or to members of the Network of Ensemble Theaters, which since 1995 has grown from eight to 200-plus member organizations.

It is true that the attenuation of the ensemble within the regional theater establishment has eroded the long-term relationships that once allowed not only for the development of a company’s style, but also for the specificity in a writer’s work that arises from the interface between art and life—between characters and the actors who embody them. Indeed, critic Lily Janiak has noted that institutional theaters have begun looking to devising as a means to solve issues with the contemporary new play development process.

In her article, “New Plays in New Ways: Redeveloping the Development Model,” Janiak quotes the artistic director of Z Space, Lisa Steindler, who observes, “Devised theater is not that new…in the ’80s and ’90s, we had companies. Nobody can afford that any more. Development processes are bringing temporary companies together as kind of an in-between.” For some theaters, connecting playwrights, directors, designers, and actors early in the process is a stopgap measure, fostering a sense of artistic community—and the richer, riskier choices that community allows.

Devising, with its emphasis on the elaboration of work that responds to a social, physical reality of the moment, seems to offer the possibility of being one of the “new ways of making theater for the present moment” for which Ruhl calls. In interviews with the leaders of theaters who have incorporated devising techniques into their play development process, Janiak found that all “spoke about how central it was to their process to develop scripts that have—and they all used similar language here—holes.” Will Arbery echoed this sentiment: “So much of devising is just staying open,” he observed, noting the importance—in filmmaking and playwriting as well as devising—of “letting the outside world step into your process at any moment, and letting the art have a dialogue with that intruding contradiction. Beautiful things can happen that way.”

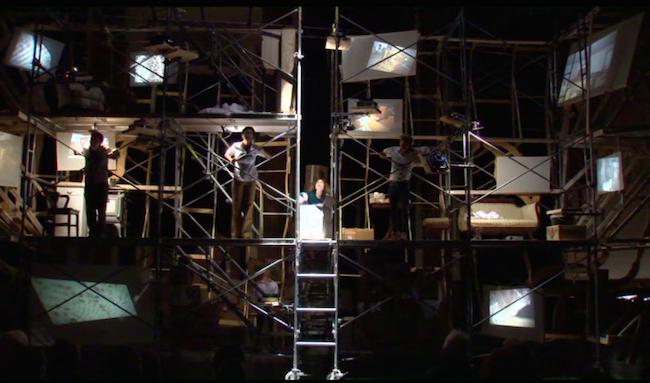

Playwright Rachel Jendrzejewski likewise described the liberation that she felt when, as a graduate student at Brown, Erik Ehn “encouraged all of us to explore what we wanted to explore, and not feel like we had to fit into these boxes of what a playwright is.” For her thesis project, Jendrzejewski worked with large-scale installation artists Megan and Murray McMillan to make a piece that was “half-play, half-visual art.” Since then, Jendrzejewski has continued to shift back and forth between her own practice and her collaborative work. “The balance feels good,” she noted, “to be thinking in different ways, working on different projects at the same time. They all inform each other.”

For Kirk Lynn, an increasingly broad definition of what playwriting is “has allowed me more tools and more joy…I think when you give up on the idea of some pure form of playwriting you lose a little clarity about what you are doing and why. I’ve lost some of that clarity. I think it makes me a better artist.” In advocating an inclusive and responsive conception of playwriting, these artists are creating space for plays that are more open to life—to the interruptions and intrusions that complicate the art, that make it messy, strange, inconvenient, rich—that make it art.

Devising and artistic multi-functionalism represent powerful and energizing responses to a theatrical ecosystem that has grown increasingly risk-averse. The new renaissance kids have created opportunities for cross-fertilization and collaboration that previously did not exist. Meanwhile, ensemble-based companies like the Rude Mechs, Radiohole, and the Elevator Repair Service have pioneered models for long-term artistic collaboration while creating original and formally fresh new works that eschew the perfect in favor of the risky, specific, and sublime.

However, artistic collaborations within the establishment continue to be fleeting, with the onus increasingly on artists to establish long-term working relationships. This results in a diverse and vital market, but also a precarious one. Without long-term, financially stable ensembles, what are the risks to the maturity of the work produced? And what are the risks to artists, given the near-impossibility of making a living in the theater? How can they sustain the increasing demands that are placed on them—of multi-functionality in addition to excellence? Of devising new ensembles in addition to new plays?

***

Pictures from MERONYMY, written by Rachel Jendrzejewski in collaboration with installation artists Megan and Murray McMillan, composer Peter Bussigel, and five actors from the Brown/Trinity Consortium. Presented at the Pell Chafee Performance Center, Providence, 2011. Image courtesy of Brown University.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here