Groundbreaking and of a Time

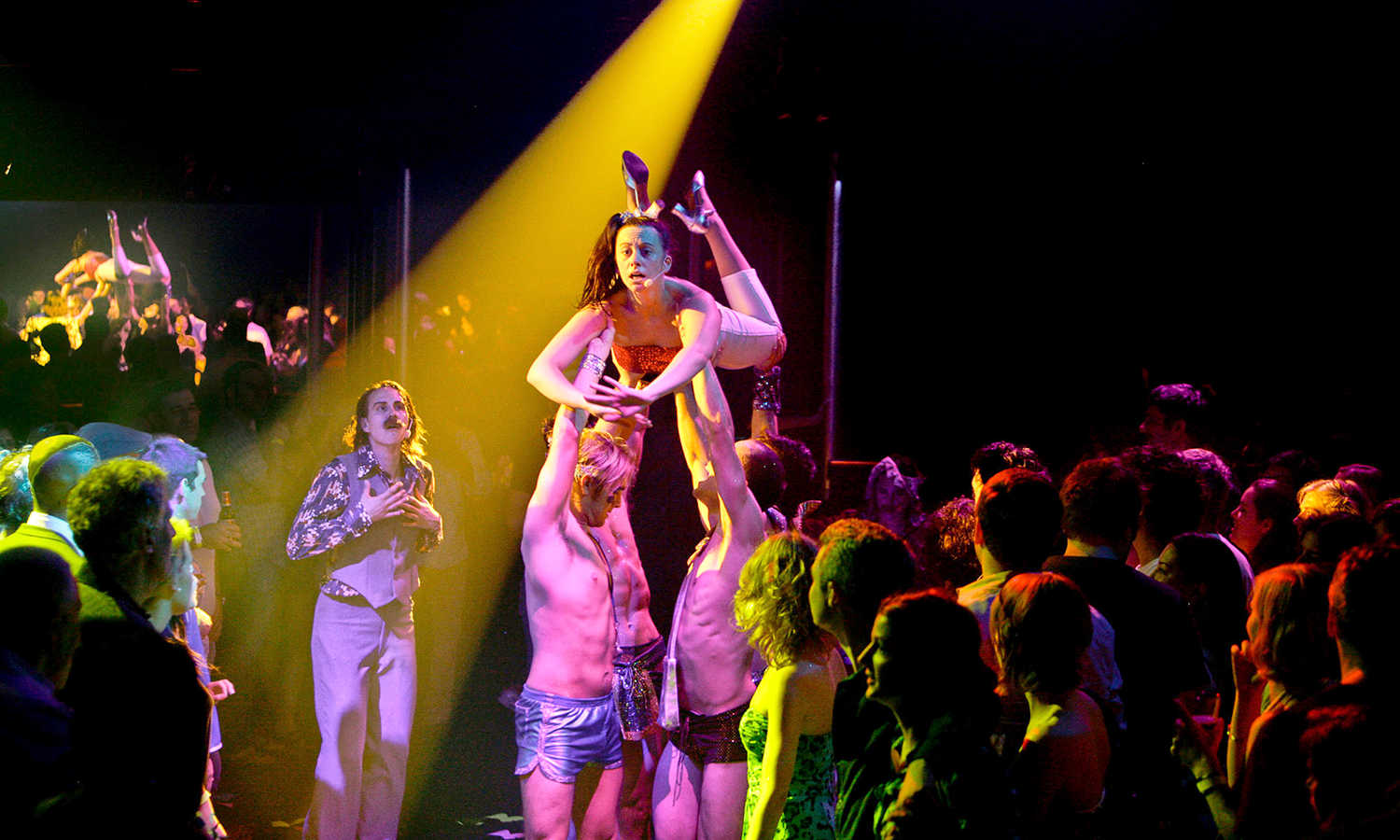

Within the Boston theatre community, it isn’t uncommon for mention of The Donkey Show to garner rolled eyes or wistful sighs—a similar response that New York critics and longtime theatregoers give to Sleep No More. Those responses seem due to the long-running status of both works and how each of them have aged alongside their many imitators. Today, The Donkey Show and Sleep No More feel less transgressive and boundary breaking than when they arrived on the scene (their journeys moving counter to one another, with Sleep No More beginning in Boston and settling in New York and The Donkey Show beginning in New York and settling in Boston). New audiences, however, have continually thrilled at discovering each of these works for the first time. Sleep No More still runs to full houses, and new audiences regularly populated the dance floor of OBERON on Saturday nights to revel in the disco lights and go-go dancers.

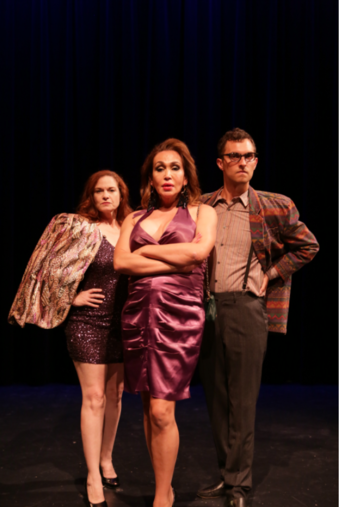

Having attended The Donkey Show over ten times in the last five years—often to bring friends for their first experience—my appreciation for the production only increased. There were numerous thoughtful directorial touches to the work that were easy to overlook amidst the sharp audience choreography, glitter drops, and barely there clothing. One standout element was the clever double casting, which involved the entire cast switching between male and female roles throughout the show, something that was only revealed to the audience in the final bows. The performer playing radiant Tytania was unmasked as the person also playing lusty, mustachioed Sander; coy Mia was also the lecherous Mr. Oberon; and the performers playing Helena and Dimitri also both played the boisterous Vinnies. At the reveal, it wasn’t uncommon to hear an audible gasp from the audience on the dance floor before a burst of applause honoring the tireless transitioning performers. Lost in the surprise is something that, for me, continued to be subversive and electrifying: the almost all-female cast was essentially doing a drag performance. Their portrayals of Sander, Dimitri, Vinnie(s), and Oberon were not simply cross-gendered casted—a common reframing device in modern Shakespeare adaptations—but were dragged, meaning that they were performed with a camp sensibility that is critiquing the “performance” of masculinity.

The Donkey Show stands as a rare work that engaged with an uncommon form of theatrical performance: female drag.

Gendered Play in Shakespeare’s Plays

Cross-gendered performance of Shakespeare has existed from his works’ very beginnings. Because women were not allowed on the Elizabethan stage, young men donned dresses, wigs, and bonnets to play female roles up until the 1660s. Almost immediately, when women took to the English stage, they were put in males clothing in what were called “breeches” roles. Elizabeth Howe notes in her 1992 book The First English Actresses: Women and Drama 1660–1700 that, despite the preponderance of breeches roles given to women—almost a quarter of plays produced between 1660 and 1700 had breeches roles—most of them were comic and sexual. Putting women in pants gave audiences ample opportunity to see the actual shape of women’s bodies, heretofore hidden beneath layers of dresses and petticoats. And while later female performers, such as Charlotte Cushman (1816–1876) and Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), propelled the playing of male characters into an art form, cross-gendered performance by men seemed to maintain a form of critical capital and acclaim in theatrical criticism. Critic Peter Ackroyd exemplifies this sentiment in his 1979 book Dressing Up: Transvestism and Drag: The History of an Obsession. Speaking of nineteenth-century female cross-dressers like Cushman and Bernhardt, Ackroyd said:

The male impersonator, the actress in trousers, seems…to lack depth and resonance…[and] is never anything more than what she pretends to be: a feminine, noble mind in a boy’s body. It is a peculiarly sentimental and therefore harmless reversal. The female impersonator, on the other hand, has more dramatic presence—the idea of a male mind and body underneath a female costume evokes memories and fears to which laughter is perhaps the best reaction.

Ackroyd’s analysis reads a little as a heterosexist/misogynist sensibility that privileges male drag performance by acknowledging the “fears” of femaleness in a male body and blesses such male drag performers with a complexity that female cross-gendered performers cannot possibly possess.

Riding the crests of first- and second-wave feminism, theatrical performance has reexamined the construct of gender in Shakespeare through various means. All-female casts tackled some of Shakespeare’s works, some of the most recent notable productions being Phyllida Lloyd’s trilogy of Julius Caesar (2012), Henry IV (2014), and The Tempest (2016). Beyond the idea of these roles being performed as breeches roles, recasting the entire work with women markedly reshaped the audiences’ interpretation of the performativity of gender and Shakespeare’s works.

Yet, while structurally The Donkey Show maintains a familial connection to all-female casts of other Shakespeare performances, in that the primary cast is usually almost all female, the show is a rare example of female drag due because of the camp aesthetic frame of the cross-gendered performance.

The campy performance of maleness is also where the divide between classical breeches performance and drag performance is vast.

Gender Goes Camp(ing)

The examination of camp as an aesthetic concept is having a revival of sorts in 2019: it was the theme for this year’s Met Gala and subsequent highly successful exhibit “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” which closed on September 8; it informed Boston’s Museum of Fine Art’s related “Gender Bending Fashion” exhibit, which closed in August; and it remains the reigning sensibility of shows like the hugely successful RuPaul’s Drag Race and almost anything Ryan Murphy produces on television. Susan Sontag’s seminal 1964 essay, “Notes on ‘Camp’” lays rich groundwork for a broad understanding of camp, and while there are a wide array of elements that make up her definition—she lists fifty-eight in all—a few specific elements ring true to the conception and performance of The Donkey Show.

In Sontag’s notes, number seven emphasizes the “large amount of artifice” in camp; the unnatural, built “urban” environment in opposition to the raw, native earth. It is compelling to regard how The Donkey Show, in its dramaturgy, removes the narrative from Shakespeare’s setting of a forest brimming with sprites and fauna and places it in the highly artificial club environment. Artifice is built into Paulus and Weiner’s set and narrative setting for the show, and in almost every other performative aspect as well: the performers don’t sing songs on their own but over the tracks of fully vocalized disco hits, in the scene of Tytania and the donkey’s copulation they are symbolized by a butterfly puppet and a donkey piñata on sticks chasing each other above the audience, and whenever a male character comes onto the stage—be it Mr. Oberon, the Vinnies, Dimitri, or Sander—they are parodically performed with overweening macho brusqueness. The characters grab their packages, pawn the women, and thrust their hips into the women.

The campy performance of maleness is also where the divide between classical breeches performance and drag performance is vast. According to photographer and drag king Del LaGrace Volcano, in The Drag King Book, “When asked, ‘What’s a Drag King?’ I reply: ‘Anyone (regardless of gender), who consciously makes a performance out of masculinity.’” LeGrace Volcano and co-author Judith “Jack” Halberstam diverge a bit on the necessity of queerness at the core of a drag king performance, but both are clear that drag king performance recognizes what Katheryn Rosenfeld calls, in her essay “Drag King Magic,” “the subtle reconfigurations of maleness.”

This conception of drag king performance comfortably squares with modern feminist and gender studies regarding the construction of gender. In “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” preeminent theorist Judith Butler says:

… gender is in no way a stable identity, or locus of agency from which various acts proceed; rather, it is an identity tenuously constituted in time – an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts. Further, gender is instituted through the stylization of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and enactments of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self.

The drag king creates a persona or character through the performance of maleness. They “camp up” maleness, honing a “stylized repetition of acts” through gestures of male privilege: a swaggering gait; wandering, groping hands; and bombastic declarations. The camping of maleness is also a parodic performance of gender. This performance is essential to Paulus and Weiner’s reconfiguration of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Audiences have long accepted drag queen performance and male camp much more openly than female camp and drag king performance.

The Catharsis of Camp

Shakespeare’s original farcical text gives short shrift to woman’s autonomy and consent—both concepts that are evolving even now in our society—making the work a difficult sell in the #MeToo era. While The Donkey Show worked to update some of the more troublesome elements of consent and autonomy in recent years, the core faculties of the Bard’s play remain uncomfortably present. I would argue that the balm for some of this in The Donkey Show is in the farcical nature of the production and the over-the-top campiness of the performances.

As a male-identified cis dramaturg/critic, I recognize that my view on this may differ from others and it is not difficult to see the drugging of Tytania, the constant pawning at all of the female characters, and forced copulation with a donkey as highly problematic. But I point to the similarity of The Donkey Show to drag king camp performance because I have seen comparable performances in various queer spaces. One type of stock drag king character is an aggressive, misogynistic, and homophobic type—who is sometimes hilariously closeted. I have watched drag king acts where a character belligerently and farcically pursues a woman in the audience, describes the vulgar things he will do with her, and, in one case, whipped out a fake penis as a proof of his manliness. All these elements are intended to be both offensive but also cathartic. By parodying the most grotesque elements of masculinity, the drag king is constructing a critique of the performance of “maleness.”

The complexity of such parody and camp echoes point forty-one in Sontag’s essay:

The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to “the serious.” One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here