Drowning Ophelia

A Metaphor for Female Pain

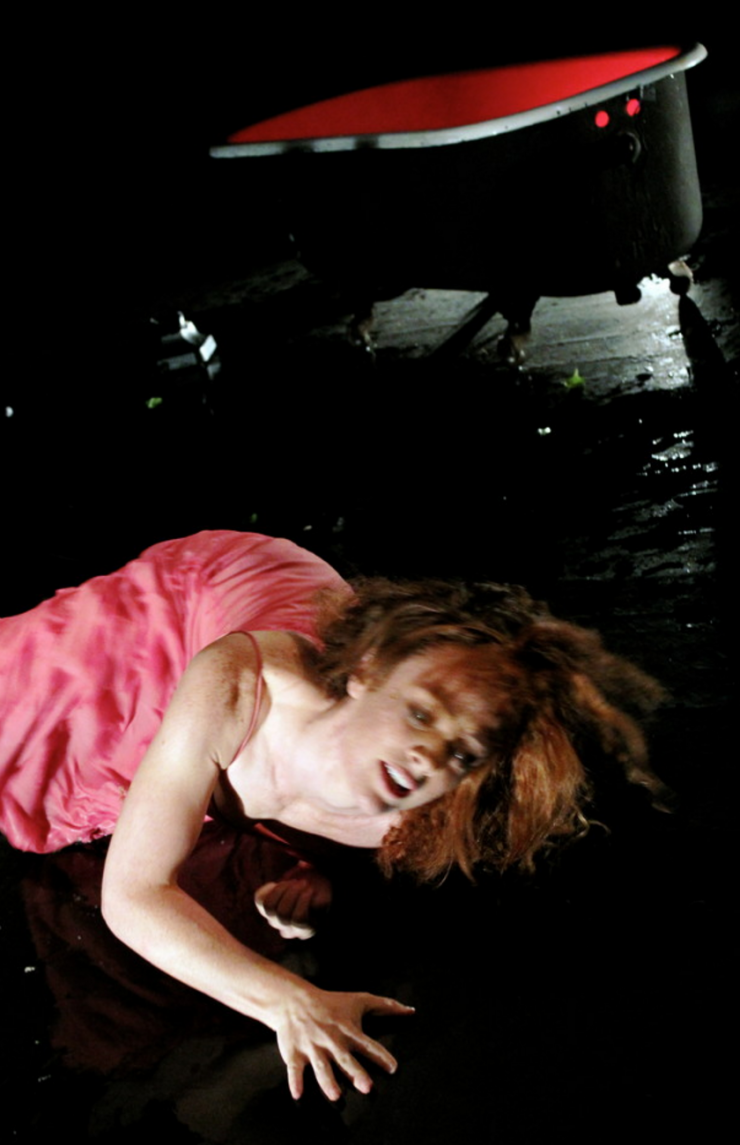

Repurposed Theatre’s production of Rachel Luann Strayer’s Drowning Ophelia offers a critic’s greatest pleasure: discovering a new company of merit. At rise the black box theater features only a bathtub, eerily lit from within like a glowing UFO by lighting designer Julien Elstob (who throughout the production eschews the norm of flooding a stage in light in favor of single instruments illuminating slices of the action from obscure angles). A young woman (called Ophelia in the program but never named, played by Kirsten Dwyer) in a long, electric pink dress frolics in this tub, which is filled with water, with the kind of abandon most children, even, have learned is not okay. This tub is her home throughout the show in the Mojo Theatre, a space inside San Francisco’s historic Redstone Building too tiny to fit more than a few risers. By contrast, Jane (Katharine Otis), a deeply troubled woman a few years older, can never acknowledge the tub. Both it and Dwyer’s character represent for her extreme pain.

Photo by Ted Davis

There appear to be a great deal of other things Jane can’t acknowledge: a series of increasingly panicked messages on her answering machine or the bizarreness of the constraints she imposes on her dating (and perhaps sole social) life: Each week, she pays Edmund (Will Trichon) to come to her home dressed in a different period costume, such as those from Jane Austen’s Regency England. They enact a period conversation over a period meal, steadily butchering period language by appending –th to verbs willy-nilly, stuffing “thou” in wherever there’s space. The meal lasts only as long as it takes for Ophelia to interrupt with childish singing of an old-time ditty, which she delivers like an urgent plea for Jane to listen and which only Jane, not Edmund, can see or hear. Jane then freaks out, screaming or writhing, much to Edmund’s bafflement.

Ophelia lives only in Jane’s mind but exerts, with her tub, a great and terrible pull over Jane’s consciousness. Much of the play’s drama derives from the slow unfolding of the mystery of their relationship and the cause of Jane’s inability to function.

If that unfolding is at times slow (successive dinner dates, for example, cover too much of the same ground), direction by Ellery Schaar shows elegance that’s uncommon in young companies. Performers move with purpose and economy, each motion precise as an incision. They interact onstage despite being divided by time and space, and Schaar makes those interactions have both the pain of separation and the urgency of intimacy.

In a way, both characters are frozen in time

And if much of the play is painful and infuriating to watch, that’s because it depicts a painful and infuriating issue in a truthful (if not necessarily realistic) way. Ophelia, it turns out (spoiler alert!), is a younger version of Jane. In a way, both characters are frozen in time as a result of Jane’s bathtub molestation by her older brother, Adam (Ryan Hayes), who later commits suicide. Ophelia is forever as Jane was right before the crime—innocent, full of tenderness for her brother, always singing. Jane, by contrast, is stuck in the instant right after the incident. Her molestation is raw, real and present with each sharp breath she sucks; she lives always in not just anger and shame, but horror and disgust, as if she were in each successive moment shocked anew. Ophelia, Jane’s younger self, and the songs she sings are for Jane manifestations of what just happened. The two characters’ battle for speech, for whose version of the story is true, signifies that Jane is trying and failing to repress that moment and move on.

The dividing of one character into two and having them interact is a device that works especially well in the theater, and it has a rich history, especially with female characters. One of the device’s chief pioneers was Marsha Norman, who used it in 1979’s Getting Out to show the character Arlene’s attempt to transition from a life of crime to the straight and narrow.

Norman's play is occasionally criticized for offering a false resolution by too easily reconciling the two selves. Critic Timothy Murray once wrote that in reconciling Arlie and Arlene by having them speak, smile, laugh and remember a childhood story in unison, Norman absolves audiences of their culpability in Arlene/Arlie’s plight: “The false promise of Getting Out for the spectators is to so displace their own responsibility for this daughter of society that they need not account for the flaws of the father, of the panoptic institution, of the very notion of legitimacy favored by our socio-legal community.”

The strength of Strayer's play, by contrast, is that its resolution is incomplete, giving audiences no false hope that Jane will magically be okay. Jane and Ophelia don’t reunite at the end of the play; rather, Jane wrestles down Ophelia and finally defeats her. After the fight, Jane can finally take over the tub, plunging in and, perhaps, undergoing a partial cleansing and rebirth. The play closes as she comes up gasping for air: stronger, given a second chance, but in no way fixed or complete or even necessarily stable—what does it mean, after all, to have just strangled your childhood self? It's a fitting ending for a play about a mourning process that will have no end, in that it could also serve as a beginning: Who Jane is when she emerges from the water would make a great beginning of another play.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here