Edward Albee’s Kindest Character

Standing in front of a group of his students, Edward Albee was asked for advice on how to handle fame. “If you’re ever in any danger, I’ll let you know,” was his reply. This quip could have come from one of his famously acerbic characters. But there was another side to Albee. When introduced in 1996 at Clackamas Community College (CCC), in a small town outside of Portland, Oregon, the host referred to Albee as America’s greatest living playwright. Stepping to the podium, Albee began, “That was a lovely introduction, but I didn’t realize Arthur Miller had died.” That generous spirit was as much a part of him as the barbs. When the obituaries rolled out after Albee’s death, they all featured his genius, but few noted his kindness.

Was there ever a giant of American theatre whose own character contained so much kindness?

I was lucky enough to hear Albee say both those things, in a rehearsal room at the University of Houston, and as a student at CCC. I was a high school dropout, struggling to find my voice as a writer, and I never considered being a playwright until Albee came to CCC. During his public talk, he mentioned that he taught playwrights at the University of Houston, and, during the Q&A, I asked how to get in. He stared me down, and replied, “Are you speaking practically or theoretically?” I had to think that through, and gulped out, “Practically.” “Send me a play,” he replied, quickly moving on to the next question. But before he left, he gave the chair of CCC’s English department the address to which I should send my play. Where others in the audience snickered at the audacity of this high school dropout asking a three-time Pulitzer Prize winner how to work with him, Albee gave me a chance. In so doing, he changed the course of my life forever, as he did for many, many others.

Albee was a producer, a teacher, and a champion of potential playwrights. In 1964, only two years after he skyrocketed to fame with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Albee produced Dutchman and The Slave by LeRoi Jones (now named Amiri Baraka) and Funnyhouse of a Negro by Adrienne Kennedy. Both these playwrights would become essential parts of the US canon, and these early productions formed keystones of the bourgeoning Off-Broadway scene. And once Albee advocated for a playwright, he didn’t stop. In 1995 Signature Theatre did a season of Kennedy’s work because, according to her, Albee put her plays in the hands of the theatre’s founder, James Houghton. Albee continued as a producer for decades after his initial foray into the role in the 1960s, championing playwrights whose voices, for one reason or another, weren’t locks for commercial success. But that kind of polish didn’t matter to him—advancing the art of theatre did.

He was faculty at the University of Houston (UH) from 1989-2003, not because he needed the gig, but because he wanted to help potential playwrights. His only requirement was that he pick his own students. The Houston Chronicle reports Albee saying, "I want to choose the ones I think have the most innate talent. Not necessarily the ones who copy other playwrights best, but burgeoning talents with potential and individuality. Some won't know how to write a play yet. But they can be encouraged and pushed to hone their skill." At UH, he not only taught, but also brought scripts to life in collaboration with Stages Repertory Theatre. He was insistent that playwrights needed to see their creations come to life, and he made sure that dozens of students got just that, even if their scripts would never have made it on to the stage of a commercial theatre.

When Albee died, my Facebook feed lit up with playwrights saying they owed their vocation to him. This often took the form of encounters at two conferences he helped create: The Last Frontier and Great Plains. At the Last Frontier, he played a role from its first gathering in 1993 until 2004. Likewise, he was at the first Great Plains conference in 2005 and was active with it for years. He was also exceptionally open to contact from fans. In 2009, for instance, long before her current success, playwright Lindsey Ferrentino wrote to Albee out of the blue, and he allowed her to interview him. Crediting this first encounter as the spark that launched her current soaring career as a playwright, she became one of the many artists Albee hosted at the William Flanagan Memorial Creative Persons Center (The Barn) in Montauk. Created in 1967 using proceeds from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, from 1970 to 2016 Albee gave artists time and space to create their work, often padding into The Barn wearing shorts to see how people’s work was coming along.

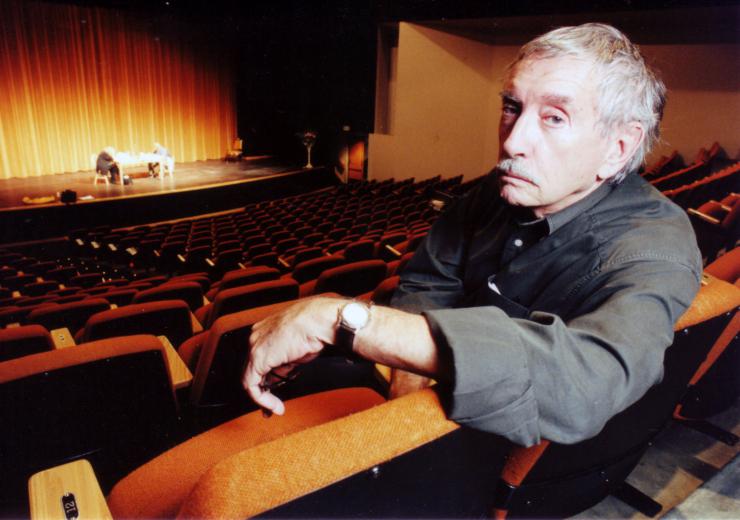

One more example of his generosity, this time from my own experience. In 1998, at Stages Repertory Theatre in Houston, Albee sat in the house during my first tech of my first about-to-be produced play. Together, we were watching a scene I had refused to rewrite despite much advice from Albee. After trying one last time to get me to change the scene, Albee said, “Well, sometimes one has to fail in front of hundreds of people to learn,” before standing and walking away.

Albee was right, both about the play and the need for public failure. As he said in another context, “If you’re willing to fail interestingly, you tend to succeed interestingly.” And, oh, did that scene fail. I still remember every way it failed. But I needed to see it, and Albee gave me that great gift. He gave hundreds of playwrights that gift, and probably gave thousands the gift of advice on their work, and even more the gift of spending time around his brilliant intellect.

But was his quip telling me that I needed to fail publically kindness or cruelty? It may have been witty, but his words were an honest critique. What could be more generous? Was there ever a giant of American theatre whose own character contained so much kindness?

I don’t think so. I hope you’ll post your own stories about Albee’s generosity in the comments below so that this page can be an online memorial.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here