Interview with Liza Ann Acosta

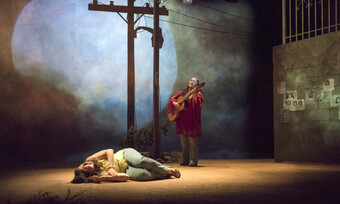

Dr. Liza Ann Acosta is the resident dramaturg at Urban Theater Company in Chicago. Her work with them began two years ago when she participated in a discussion following the staged reading of Carmen Rivera’s play Julia de Burgos: Child of Water, based on the life of the Puerto Rican poet of the same name. de Burgos life and work centered on cultivating her voice as a woman and advocating for social justice. After the staged reading, UTC produced that play in November 2014, along with Adoration of the Old Woman by José Rivera (February 2016), and Lolita de Lares by Migdalia Cruz (June 2016), a play about Dolores (Lolita) Lebron, a Puerto Rican Nationalist Party member who went to prison for spearheading the 1954 armed uprising in the U.S. House of Representatives. UTC, a ten-year old company, views their work in Humboldt Park as “a bridge between Chicago’s urban and Latino communities.” Their three most recent plays feature strong, Puerto Rican women as protagonists whose stories interact personally and politically with Puerto Rican history and cultural identity. Recently, I sat down with Liza Ann to talk about her work.

Liza Ann Acosta: I had been doing dramaturgy before Urban Theater Company, but it was in another capacity. I was a literary manager at Teatro Luna. That work is different because TL is an ensemble that devises original work. This was my first role as a dramaturg on single author plays in production. Obviously, having been a part of an all women, all Latina theatre company, the importance of the central female characters in the plays enhanced my enthusiasm for the work. I was also really affected by the opportunity to delve into Puerto Rican history and look specifically at women. Julia de Burgos and Lolita Lebrón are significant characters pivotal in the history of our nation. I knew Julia de Burgos as a poet but not necessarily as a political figure so delving into each of their histories was important to me. I immersed myself in their stories and the history of Puerto Rico, something I have been very eagerly embracing the longer I am here in the US. This research has been an important part of my growth as a person.

Priscilla Page: What more did you learn about Julia de Burgos through this process?

Liza Ann: Well, this is interesting because I am not a big poetry fan. I appreciate poetry as a literature professor; I understand the value of poetry and I teach it, but I don't read poetry for pleasure. I had an opportunity to get into her poetry. I learned that her work as a poet was feminist and political. Yo misma fui mi ruta was one poem that was meaningful to me. It made me appreciate her struggle as a woman. And once I like a poem, I love a poem; I focus on it. I meditate with it. It's like a prayer. It's my lectio divina. It helped me identify my own struggle as a single independent woman in this world. I now see that her disastrous romantic life really was a disaster precisely because of her independence. The tension comes from the drive to be her own person outside of a relationship with a man while being a person filled with love, desire, and passion. That to me was a very intimate discovery.

I also appreciated the racial aspect of who she was. I think there has been a whitening of Julia. Her Afro-Puerto Rican heritage affected her relationships with men of a particular class. Her blackness was seen as an impediment. She was seen as less human because of her ancestry, because of her skin tone. We explored this discovery with the cast.

Priscilla: With Adoration of the Old Woman, Rivera does not deal with iconic women; instead he portrays a lineage of Puerto Rican women. What came up for you in these depictions?

Liza Ann: What I admire about this play is its political angle. I have some mixed feelings about how the women are portrayed in this play. I am interested in some of the racial implications between the two main characters, Adoración and Doña Belen. I am very interested in the integration of historical events and how they are blended in a sort of alternate present—slash—future. I like how Rivera plays with time. There is the echo of the past repeating itself into the present. He creates the character Cheo who is reminiscent of the historical freedom fighter Ramón Emeterio Betances. Rivera addresses all the issues that emanate from our status as a territory, the constant referendums, the environmental issues with reference to the disappearance of the coqui and the privatization of the beaches. These are all ongoing issues. This play was first produced in 2002 but just last week, the question of who gets to use the beaches was in the news. Because of the debt crisis, the government wants to privatize more beaches. And so we repeat the same issues time and again.

Priscilla: Even though it’s a play set in the near future, we have this vote on Puerto Rico’s status looming (which has actually occurred five times since the 1960s); and we have Cheo who becomes a martyr for independence movement. It's not a hopeful play. It asks us to look at the cycle of colonization and recolonization.

Liza Ann: Yes, it looks specifically at the questions surrounding the referendums. Every time we vote, it is the same. Puerto Rico’s colonial status remains intact. We repeat it over and over again. Is it like Sisyphus? Are we condemned to keep repeating this event over and over with no solution, with no answer? Is this our fate?

There is a silencing of our people. And with 'Lolita de Lares' we see the effect of that silencing, the process of that silencing, and the consequences of that silencing. It's painful but is has been an incredible gift to be able to understand this.

Priscilla: That's a provocative question that is present in each of these plays. Can we talk about Lolita de Lares and your reflections on that, the most recent of the three productions, at UTC?

Liza Ann: There are things that I am just beginning to learn about this city and Puerto Rican history. It's like you know these things but you don't really know and then I learn more and I know that I have to do my homework. I want to know more about the connections between nationalism, culture, and identity in Chicago that is different from New York and different from the island where I grew up. I feel more connected to home by working on these plays. It has been a gift to learn more about Pedro Albizu Campos, one of the leaders in Puerto Rico’s independence movement, through my research. He was born in Ponce, where I grew up. It's been an honor just to understand more about his work and the influence he had on others. We can agree or disagree with the actions that he and Lolita, and others, felt compelled to take in order to pursue their ideals but we cannot deny the fact that they are a part of the revolutionary history of our country. Many people of our generation have not had the opportunity to learn about them because it was dangerous to know or discuss what they did.

I feel more connected to home by working on these plays.—Liza Ann Acosta

Today, I better understand why people reacted the way they did to Lolita, why they voted the way they did, and why they spoke about ideals the way they did. People who lived during that time experienced a kind of terror and lived in fear. This helped me understand my own family. The personal is political. The Puerto Rican who is not political is a strange creature, indeed. My mother claimed to be apolitical and I have actually learned that she is far from it. There is a silencing of our people. And with this particular play we see the effect of that silencing, the process of that silencing, and the consequences of that silencing. It's painful but is has been an incredible gift to be able to understand this. And the audience response to this play has been really moving. You know, for Julia de Burgos, audience members said "Finally! We get to know her story." For Adoration of the Old Woman, the audiences often reflected on the never-ending cycle of oppression, and for some there was a feeling of resignation. But for Lolita de Lares, I have seen men and women, especially older people who were probably kids when the gag law was enacted in 1948, who saw this onstage and it was so cathartic for them. That surprised me. I didn't expect to see that from the audience.

Priscilla: Can we talk about how you see feminism in each of the plays?

Liza Ann: I have to say that Julia de Burgos and Lolita Lebrón appear as strong feminist figures who defied certain societal conventions of their times. They were women who marked the paths of their own destinies and suffered the consequences for doing so at a time that didn’t welcome that. In Adoration of the Old Woman, the idea of feminism gets complicated. We see two women who are sort of crass regarding their sexuality. Adoración is a woman of color; she is hyper-sexualized, and she only appears in the bed. She's also very political and she aligns herself with the laborers in the field. In contrast, Doña Belen presents a tension between being the prude and the hypersexual female at the same time.

With the character Vanessa, I have a very hard time with a seventeen-year-old woman who is encouraged to date a man much older than her. He is probably twice her age. I have some questions about this young character. She seems to be very precocious but I'm not sure how her sexuality advances any political issues. In the case of Julia and Lolita. Lolita is not sexualized. She has children. The way she defies conventions is that she abandons her children. She says I am going to sacrifice for something else and my children are going to have to pay that price. Julia de Burgos says, “I love and I am just going to be with the person that I love.” These two women lived through their convictions. I am not sure that the conviction and the sexuality portrayed in Adoration advances any ideas about conviction, about politics, and I am not saying that it is gratuitous but I think that this is the heart of the problem in the portrayal of the women in that play.

Priscilla: In some ways, Lolita and Julia have command of their sexuality and their agency comes through this command and in some ways even though the women figure prominently in Adoration, the men have political agency in their public lives and sexual agency because they present themselves as potential suitors to the young woman.

Liza Ann: And the women don't have agency. Is that the message of the play? I don't know. I am not sure about the idea that women don't have political agency. Is this a commentary on our reality? Is it the reality that women do not have power over their own sexuality? Maybe.

Priscilla: When you work on a play, you think about how to best reconcile these challenges. I was also thinking about these three plays and the presence of dreams in them. Dreams are a powerful way to frame these plays and feel like hauntings.

Do you see a connection between the dreams and memories, which are sometimes nostalgic or hopeful, and larger ideas about Puerto's Rico's freedom?

Liza Ann: That is interesting. In Julia and Lolita maybe these dreams are hopeful like you say. In Lolita, she has nightmares about her children and that may be an expression of her guilt or regret. But in Adoration, they are nightmares. One question I have is, “Can we only live off dreams?” Put another way, we only have our dreams and it may seem hopeful, but maybe it’s not that hopeful. When will our freedom become a reality? Because our liberation is so uncertain, the only way to express it is through this dreamscape.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here