I arrived at the island of Štrelecky ostrov on a mild June morning, the Charles Bridge and the Prague Castle in postcard-perfect formation in the distance. Carmen Lee, executive director of Theatre du Poulet and co-creator and co-director of Be Water, My Friend, hailed me with an unusual greeting: a drop of water she entrusted into my care. I carried the water, drawn from the Vltava River which coursed around the island, on the back of my hand. Then I added the water to a cascade of drops created by all the audience-participants in that morning’s performance. It was our first lesson in the power of collectivity: alone, our drops were vulnerable to evaporation or absorption, but together they created a waterfall. As a group, we manipulated the water on a clear plastic tarp redolent of a theatre game.

Performance, Pro-Democracy Protest, and Activism Across Cultures

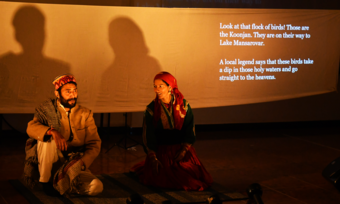

Roland Chun Shing Au (center) with audience members in Be Water, My Friend produced by Theatre du Poulet at the Prague Quadrennial. Idea conceived by Carmen Lee. Co-created and co-directed by Chun Shing Au, Greta Katharina Klein, Levin Eichert. Based on the experiences of Carmen Lee and Chun Shing Au. Photo by Michal Hancovsky.

This might seem like an uncharacteristically bucolic start to a work of protest art, but Be Water, My Friend is no ordinary act of resistance. Conceived by Lee during her time as a graduate student at DAMU (The Academy of Performing Arts in Prague) and developed with her creative partner and Theatre du Poulet’s artistic director Roland Chun Shing Au, along with Greta Katharina Klein and Levin Eichert, this ambulatory, participatory performance was a direct response to the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests of 2019. Originally from Hong Kong, based in Canada, and performing in the Czech Republic, Theatre du Poulet crafted a piece that’s profoundly local and fundamentally global.

Lee conceived the piece after she and Au arrived for a visit in Hong Kong, landing on the day mass demonstrations broke out in protest against a bill that would permit extradition to mainland China. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets. This bill was a flash point after Beijing had slowly restricted Hong Kong’s special status as a semi-autonomous region with protections for freedom of speech, press, and assembly. Though then-chief executive Carrie Lam later rescinded the bill, civil unrest continued to grow in the wake of crackdowns from Beijing and the police. Protestors’ demands included universal suffrage for Hong Kong citizens, enshrining democracy into the Special Administrative Region’s governance.

For Lee and Au, the question was about the role of artists in these protests and the movement for democracy. The answer was how I ended up on Štrelecky ostrov. I saw the performance as part of the 2023 Prague Quadrennial, an international festival of scenography featuring a series of performances called PQ Studio. After Be Water, My Friend’s initiation with the cascade of water drops, the audience was instructed to open the Telegram apps on our phones. On the app, a bot named Blue Ocean Thunder, our automated guide, invited me to find an isolated spot to experience the next portion of the performance. This section was characterized by its liminality: an experience both public and private, an act of both art and activism, located on two islands—Štrelecky ostrov and Hong Kong.

Via Telegram, Blue Ocean Thunder reminded us that,

Sitting on this island, you are not only surrounded by the river, but also in between two riverbanks, two different sides. Several times the Vltava flooded the adjacent land. 💦 From this river, I want to take you to on a trip to Hong Kong. 🇭🇰 ✨ From the ‘the riverside of Vltava’ to ‘the riverside of 深圳河 (Sham Chun River). 深圳河 is the largest river in Hong Kong. This river works as a border between Hong Kong 🇭🇰 and China 🇨🇳.

In a stunning marriage of form and content, Telegram—the way I was “watching” the play—was also the app that pro-democracy protestors used to communicate about their demonstrations. To avoid censorship and detection, protestors chatted in codes, such as using the language of school carpools to coordinate rides for protestors to and from demonstrations, as well as pickups from jail. I learned all this from my disembodied performer, Blue Ocean Thunder. Most chilling for me, though, was an image of protestors holding up blank posterboards after their slogans had been banned. As I paused to absorb the full weight of this image, I glanced up and around at my fellow audience members to see if they too were overcome by this moment. Scattered around the island, they were engrossed in their own private journeys through the piece. Returning to Telegram, Blue Ocean Thunder explained that the metaphor of water came to the protestors via Bruce Lee: “‘Be Water’ 💧 became a strategy for pop-up, guerilla protest, a type of resistance characterized by changing form and direction suddenly,” much like the performance of Be Water, My Friend itself.

If you could write one short sentence the whole world could see, what would you write?

Blue Ocean Thunder invited me to meet back up with one of the live performers, who gave me and a group of three other audience-participants a new task: to hold water in an open sheet of saran wrap and carry it over a bridge, across a busy intersection, and into Václav Havel Square in front of the Národní divadlo (the National Theatre). There, our river water found its ultimate purpose. It was added to a large bucket where Lee and Au used mops and a pressure sprayer to write protest messages in water. Blue Ocean Thunder had posed a question that had been eating at me along my whole watery journey: if you could write one short sentence the whole world could see, what would you write?

Václav Havel Square has its own chapter in the history of theatre and protest. Havel—the stagehand turned playwright turned dissident—became the first president of Czechoslovakia after the Velvet Revolution. His ascendancy to the presidency came after scenographer Joseph Svboda stepped in during the 1989 pro-democracy protests against one-party communist rule in Czechoslovakia. In November 1989, Svoboda announced that his company Laterna magika—which invented multimedia theatre and is now in residence at the Národní divadlo—was joining the country’s general strike. Laterna magika’s theatre became the headquarters for Havel’s group, the Civic Forum. Each night at curtain, the theatre opened its doors for peaceful gatherings of protestors instead of performances. “This is where all the important decisions were made and where journalists from all over the world gathered to report on the events leading to the fall of the Communist regime,” wrote Ruth Fraňková of Radio Prague International. In Modern Czech Theatre: Reflector and Conscience of a Nation, Jarka M. Burian called Laterna magika “the cradle of the revolution.” The Velvet Revolution came to a bloodless end in December with the election of Václav Havel as president.

Carmen Lee and audience members in Be Water, My Friend produced by Theatre du Poulet at the Prague Quadrennial. Idea conceived by Carmen Lee. Co-created and co-directed by Chun Shing Au, Greta Katharina Klein, Levin Eichert. Based on the experiences of Carmen Lee and Chun Shing Au. Photo by Michal Hancovsky.

In creating a piece that literally bridged an island in a river evocative of Hong Kong’s Sham Chun River to one of the most significant symbols of theatrical protest in Europe, Theatre du Poulet mapped their work onto a living legacy of performance, resistance, and democratic movements—crossing cultures, political regimes, and time periods.

Havel’s presence loomed large as Lee and Au wrote messages in huge letters across the square, ranging from the practical to the philosophical: Do you know first aid and self-defense? Can you run fast enough? Write fast enough? If your words would disappear, would you still write? Then they offered us sponges and invited the audience to join in. I stood, sponge in hand, frozen. I found the pressure to distill my thoughts into one sentence unbearable. I thought of the blank posterboards. I thought about my work as a playwright, writing plays about the climate crisis. I thought about the artistic director who said to me, “Do you really think audiences want to see stories about that? It’s such a downer.”

Painstakingly, I wetted the sponge and got down on my hands and knees. The world is burning, I scrawled. I had to go back to the bucket many more times than I’d realized. I finished my message, be water. It was an homage to a line from Barbara Kingsolver’s novel The Poisonwood Bible: “I knew Rome was burning, but I had just enough water to scrub the floors, so I did what I could.”

Civic employee erasing the text in Be Water, My Friend produced by Theatre du Poulet at the Prague Quadrennial. Idea conceived by Carmen Lee. Co-created and co-directed by Chun Shing Au, Greta Katharina Klein, Levin Eichert. Based on the experiences of Carmen Lee and Chun Shing Au. Photo by Michal Hancovsky.

I was distracted from my task by something truly remarkable. Across the square, an employee of either the city or the National Theatre, I couldn’t tell, sauntered across the square in sunglasses, pants rolled up to his knees, and wellingtons. He carried a hose that he used to erase Au’s largest words, the letters Be Water two meters high on the side of the National Theatre. At first I couldn’t tell if this was a planned part of the performance. Our words were already evaporating in the growing heat of the day. Our messages were always meant to disappear. Yet here this official representative was drowning out these protest messages with… more water. It became clear this was unplanned. We wrote, and he hosed. His tool was faster, more effective, and his objective was blunter: to eliminate our words.

Democracy is rising. Like the tide, it ebbs and flows, but it will not go away.

The symbolism was striking. However, I remembered the Bruce Lee ideology that underpinned the Hong Kong protestors’ strategies: “You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.” In carrying out his duties, likely just trying to do his job, he became part of the performance. With the symbolic weight of authority that he assumed, on the surface he wiped out the climax of the piece. Paradoxically, though, he added water to the cascade. He turned our walls and the concrete of the square into the blank posterboard. He made our words, and Lee, Au, Klein, and Eichert’s ideas, even more powerful. Because water is inexorable. It can be dammed, levies can be erected, rivers can be redirected. But Be Water, My Friend demonstrates that the tide of democracy is rising. Like the tide, it ebbs and flows, but it will not go away. Like the Vltava, it may still flood the adjacent land.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here