Playing Around with Nineteenth-Century Theatre in Dr. Robert Davis’s Broadway: 1849

Theatre History Podcast #65

Dr. Robert Davis has been studying the world of nineteenth-century theatre in New York City for much of his career, but he’s recently engaged with that world in a new and unconventional way. Robert is the author of Broadway: 1849, an online game and app that takes the form of a multiple-choice novel. Players can explore what it was like to manage a theatre in the 1840s and navigate the outsized personalities and harrowing events that marked the theatrical world of the period. Robert joined us to talk about how his game reflects New York’s social, political, and artistic history, as well as the ways in which turning this subject matter into a game provide a new perspective on historical events.

Links and Additional Reading:

- Learn more about Broadway: 1849 at its website.

- Find out about Robert’s work at his personal blog and connect with him on Twitter.

- Read a contemporary account of the Astor Place Riot(s), the climactic event of Broadway: 1849.

- Find out more about the Astor Place Riots in this episode of The Bowery Boys.

- Meet Ned Buntline, a major figure in Broadway: 1849 and an important part of New York’s political and cultural milieu in the 1840s, in this article by Bruce Coggeshall.

- Read Robert’s article about Thomas Hamblin, the infamous New York theatrical producer who plays a role in Broadway: 1849.

- You can find a copy of the dime novel New York Nell, the Boy-Girl Detective, which forms the basis for a character in Broadway: 1849, here.

- Explore The Lost Museum, a site from The City University of New York that recreates P.T. Barnum’s American Museum and sheds light on life and culture in the world of Broadway: 1849.

- You can explore the newspapers that form the basis for much of Robert’s scholarly and creative work by visiting the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America project (remember to narrow your search results by specifying dates and locations).

- Read some of the plays that are mentioned in or which influenced Broadway: 1849:

- Dion Boucicault’s The Poor of New York

- Anna Cora Mowatt’s Fashion

- Louisa Medina’s adaptation of The Last Days of Pompeii

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

Transcript:

Michael Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a free and open platform for theatre-makers worldwide. It's available on iTunes, Google Play, and HowlRound.com.

Hi, and welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Michael Lueger. Could you make it as the manager of a New York City theatre in the 1840s? That's the question that players of the game Broadway: 1849 grapple with. Its creator, Dr. Robert Davis, is our guest for this episode. Robert teaches in the Tisch Drama Department at New York University, the English Department at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and the graduate program at Hunter College. He's also a contributing editor at Lady Science, an independent magazine focused on women in the history and popular culture of science. Robert, thank you so much for joining us.

Robert Davis: Thanks for having me here.

Michael: Can you explain what Broadway: 1849 is and how it works?

Robert: Sure. Broadway: 1849 is, I guess technically, interactive fiction, which is essentially like a Choose Your Own Adventure novel, if you remember those things. Although those are I think pretty rotten, poorly designed. I wrote this for a company called Choice of Games, which publishes a lot of this kind of thing. I guess the clearest way to think about it is that it's a multiple-choice novel. It's about 150,000 words long, and you essentially play a character. You get to decide everything about their background, who they are. You can play as gay, straight, bi, asexual, man, woman, gender neutral, and you essentially manage a theatre throughout the year of 1849, which culminated in the Astor Place riots.

And so, you start off, and you build up these statistics based on who you think you are, what your skills are, and those statistics get tested throughout the game and ultimately give you several different possible outcomes.

Michael: The title, Broadway: 1849, can you take us back to that year? Can you explain what life in New York's theatre scene is like?

Robert: Sure. I guess the most important thing is it was pretty chaotic and uncertain. One of the things that attracts me to that period in the nineteenth century is that we tend to think of theatre as being kind of in its own bubble, culturally speak. But at that time in antebellum period, particularly in big cities, theatre was one of the main outlets of popular culture. And where a lot of people's domestic homes did not have parlors and places to congregate, a lot of people for their basic social interaction went to the theatre. Now with that said, New York was a pretty small place at the time. As a general rule of thumb, if you know the city, Union Square is about the top of where people really live.

So it was pretty small. There was not a huge population. The theatres were deeply in competition with each other, and survival was really never a given because it was purely a commercial enterprise and you had lots of competition. Since you didn't have a huge audience base, you really had to change your bills a lot. I mean, there was some long runs, but a really long run at the time would be like twenty performances, which would be kind of like massive, out-of-control blockbuster. So things were changing all the time, often every single day. You never really knew what was coming up, and you were always keeping your eye on the other theatres and trying to carve out your own identity.

Inside the theatres, I guess the most ... The thing that makes theatre at the time so different is essentially the lack of house lights going down. So, there are chandeliers. The audience can see each other all the time. And because there's not that many people in the city, every social class is going to every theatre every night. And so, like in an Elizabethan theatre where you have the groundlings and the people paying for nicer seats, you have the same kind of structure in the 1840s for most theatres. So there's a time when all these different audiences are coming together, and they're often in pretty open conflict.

New York in the 1840s was a really volatile time much like our own era. And so, you have this play going on. You have these people socializing with each other. You have them antagonizing the other classes. It's just like everything's happening at once in the theatre.

Michael: Can you talk a little bit more about the business of running a theatre like this? Your game features these really both interesting, historical details but also some kind of fraught negotiations with characters like Thomas Hamblin.

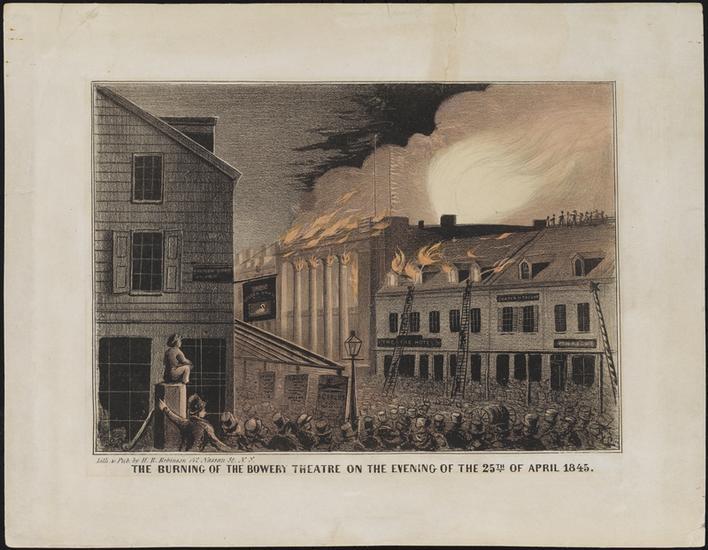

Robert: Yes, so, I got to say, I love the 1840s. I would absolutely not want to run a theatre in the 1840s. You know, outside of constantly being worried about money, you got to worry about fire a whole lot. The Bowery Theatre, which was around from roughly the 1820s to the 1920s burned down like seven times in that period. It was definitely a time of very big personalities that you had to be friendly with but also completely dominate. You had to get along with your rivals, which is I think something that I kind of try to put in there. At the same time, you were trying to backstab them, and you had conflicts with the press because the press would be allied or against you or supporting you.

Thomas Hamblin famously burst into the New York Herald's office and beat the editor in the office. But Thomas Hamblin is a horrible person and really fairly ruthless in his business and possibly a murderer. But that's sort of lost history.

Michael: Okay, possibly a murderer? You've piqued my interest. I think I need to hear a little bit more about Thomas Hamblin.

Robert: Yes, well, Thomas Hamblin is quite possibly one of the most significant theatre figures in the nineteenth century who possibly gets somewhat brushed over because he's not part of the late nineteenth century drive to respectability, like Edwin Booth is. But Hamblin was an English actor and he managed the Bowery Theatre, which really was the first, almost dedicated home to working-class, what they called, blood and thunder melodrama. This is the kind of place that Edwin Forrest really felt like home at. It was also extraordinarily successful, and in a way, I think put New York theatre on a map.

The period that he managed it kind of saw theatre get more stable and more entrenched in American society. He was, however, entirely, like an unscrupulous person. In the beginning of the game, you meet him, and he's with his wife Louisa Medina, who is of all the people in history, if I had to have dinner with one person, it's probably Louisa Medina. She was a immigrant from Spain. She spoke ... let me see ... English, French, Spanish, Italian, Latin, and Greek, and she could do algebra and, I think, calculus. She also wrote ... She was one of the first people to really earn their living by writing.

She wrote, particularly, The Last Days of Pompeii, which in the game you can produce, and it was really one of the first real blockbusters of the nineteenth century. She was brilliant. I mean, how he got to her ... He was married to a woman ... Okay. Here's a somewhat long story. It's very interesting. So he's married, he has his first wife, and I'm going to probably get the details wrong. A woman came to him, a young woman named Josephine Clifton, and she was like, "I want to be an actress." He essentially was like, "Okay, fine. I'll put you in plays, but you have to sleep with me." It was a time when there's no regular route into the theatre. She apparently engaged in that relationship.

But then he just cast her aside when he was bored with her, and she struggled through a lot of her career, and she had to tour abroad as well. He was really someone who would always take advantage of somebody else if he could. His wife, when she found out about that and some of his other doings. He was a very regular patron of brothels, et cetera. She divorced him. So, he got divorced from her. Then he was taking up with another woman who he wasn't really allowed to marry because of the terms of his divorce, but he called this woman his wife anyway.

Anyway, she died, and their nanny was Louisa Medina. So he took up with Louisa Medina, and they started to live together as man and wife. Then a woman who turned out to be Josephine Clifton's half-sister named Louisa Miller or Louisa Missouri Miller who is a character that you can romance in the game. She came to Hamblin, and she said, "Hey Hamblin. I want to be a star." He basically did the same thing with Clifton. He was like, "Okay, you can. I'll put you in a play, but you have to be my mistress." She was like, "Okay, fine." We don't totally know what coercion happened there. But he ended up putting her in a starring role in one of Louisa Medina's plays, and she did very well apparently.

Then it turned out that her mother, Adeline Miller, was a notorious, ruthless brothel madam from New York and Philadelphia. I don't think Louisa Miller knew this about her mom. But her mom wanted her back because her mom was like, "Hamblin is a bad dude. You don't want to be around with him." When you have this really evil brothel owner/gangster being like, "Stay away from that guy," you know he's trouble. So she tries to abduct Louisa, who apparently flees to the roof of the building, and kind of like in movies, does one of these chases where she's jumping from building to building on rooftops.

She eventually gets away, and Hamblin goes to court and gets custody of her because she's only seventeen. So she goes to live with Hamblin, who she's sleeping with apparently and Medina, who's apparently Hamblin's wife. They apparently get along fine. Then when July, she suddenly ... Miller suddenly dies of brain fever, which is that catch-all medical term for what they thought would happen if women got too excited at the time period. So she dies, and as July. Then in October, Medina dies of very similar symptoms. From looking at the coroner's report to Medina's death, all the doctors who performed an autopsy are constantly saying, "But I swear it wasn't poisoned."

So there's a quite decent likelihood that Hamblin murdered all these people and got away with it quite fine. I mean, I'm leaving out like a duel and stuff like that. But that's like one year of his life.

Michael: Yes, you mentioned these big personalities, and there are a number of other really interesting historical characters in here—people like Ned Buntline, Anna Ballard. Could you tell us about some of the real-life historical people that we meet in the game?

Robert: Sure. This is really one of the reasons why I made the game. I think almost every single person in there is a historical figure or comes out of a melodrama. I take some liberties. I don't think Anna Ballard was really quite that established at the time. But I'm fairly true I think to who some of the people are. So Ned Buntline is like the nineteenth century and all of its contradictions. He was one of the people who was charged with instigating the Astor Place riots. Although the degree which he did that was debatable. He was a really big proponent of the American Party or sometimes called the Native American Party.

He was essentially somebody who hated immigrants, felt like they were taking their jobs, wanted to destroy the elites, and wanted to have America for Americans, which is a fairly familiar political impulse today. But he was also a bestselling novelist, a journalist, and he would go on to essentially create the dime novel and launched the career of Buffalo Bill. But it's a good sense of who he is. Before he came to New York, there's this great sequence of events where he's in Kentucky, I believe. He had fought a duel with a man because he had slept with a man's wife, and he had killed a man in a duel.

While he was on trial for that killing, the man's brother jumped up and shot Buntline. Instead of hanging around, Buntline jumped out the window and fled. The brother got a posse, and they captured Buntline. They literally hung him, and he was hanging and dying when his friends came and rescued him. Then he comes to New York City and all of a sudden is like this major, political, and literary star more or less. I mean, there's other people, Abby Meade who is a prostitute and theatre aficionado that you can meet and get acquainted with. She had a very fancy brothel around the time period.

Matilda Heron is an actress you can hire, and she's one of my favorite really 1850s actors because she broke a lot of stereotypes. I mean, there's a lot of ... Part of what I did was just throw in side characters as well. My editor was actually on Jeopardy, and she answered a question about the author of Varney the Vampire, an 1840s early vampire novels. So I threw him in just for fun. It was kind of like this playground of great, colorful characters.

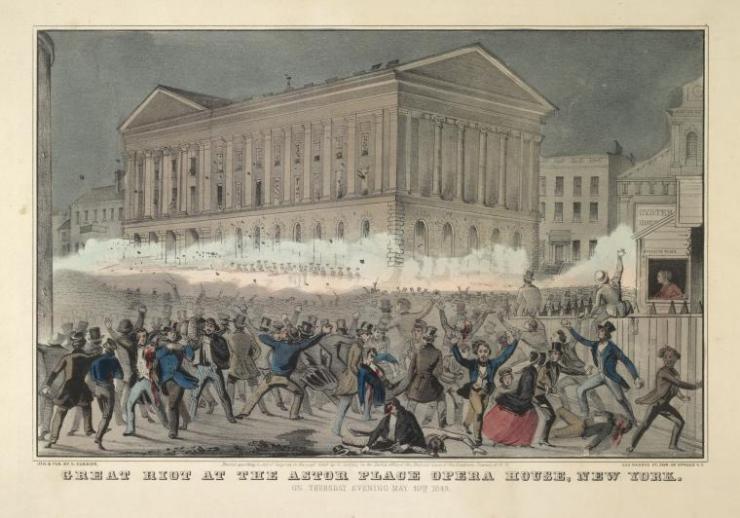

Michael: Speaking of colorful characters and the conflicts between them, the game, the plot of the game culminates in the Astor Place Riot of 1849. Listeners might be a little bit familiar with this, but can you talk a little bit more about what this event was? How it came about? And, why it was significant?

Robert: Sure. I'll say, first of all, my pet peeve of history outside of when people say that the Greeks wore togas is that it's really the Astor Place riots and the plural. The thing about the riots is that it brings so much of the time period, so many of the social, cultural, political tensions together. It's often blamed on a feud between Edwin Forrest who is in the game and William McCready who's in the game, who's a complete jerk, and actually I downplayed his jerkiness. But really, it has this vast, economic, cultural series of animosities that erupted at the time.

And really, they begin, like I believe it was on a Tuesday in early May, in 1849, when McCready comes to play Macbeth at the Astor Place Opera House, and the members of the audience riot and I think throw eggs and have banners saying, "McCready, go home." He's going to leave, but the elite of the city begged him to stay, and they get the poor mayor who had been inaugurated three days before. They get him to pledge to send out militia to guard the theatre, which he does, which is fairly unprecedented and really just made it all worse. McCready performs again later that week, and the same thing happens albeit in a lesser level inside.

But outside in the square, there's thousands of people rioting, and they're rioting because they hate McCready. They're rioting because they hate the British. They're rioting because they hate New York City Elite or the Upper Ten, as they called them, for the upper 10,000. Some of them seem to be rioting just because it seems like a fun thing to do, which, you know, is somewhat ... you're in New York. Some of the people who were later killed were just like, heard a commotion and walked down to see what was going on and got hit by a ricocheting bullet. But the crowd got increasingly agitated outside, and they started throwing things at the troops and at the opera house. McCready fled in disguise.

And ultimately, the captain of the militia ordered the militia to fire into the crowd. It was so packed that people didn't realize it was happening until the third volley. When it was all over, like twenty-four-ish people died, which is not the hugest body count, but it was the first time that anybody had fired into a crowd since the Boston Massacre, which was seen to have started the American Revolution. So really, New York City and the eastern seaboard freaked out thinking there would be a literal class war going on now. There was a rally in City Hall Park the next day, with like 3,000 people went to it, and they marched on the opera house with the intent to burn it to the ground because it was a symbol of everything they hated.

But the militia was very well prepared, not just with infantry but with cavalry and with cannons. Ultimately, there was just some chanting and insults, and I think one cavalry member fell off their horse and hurt themselves, but it kind of dissipated after that. But really it was this shockwave into American cultural history and social industry at the time.

Michael: Now, you talk about these historical events that are recorded, and we know that they actually happened. But one of the entertaining parts of the game is also these melodramatic touches. These moments where we're kind of departing from history, possibly from reality to some degree, and I'm curious about how you thought about balancing the strictly historical part of the game with some of those more melodramatic touches.

Robert: Well I'll say that part of the plots and characters are drawn from melodrama. If you know Boucicault's play, The Poor of New York, which was I believe a 1850s play. There's some characters from that in which you relive some situations from it. Badger, Puffy, and Bloodgood are all characters that I just lifted from that because I really like the play. Probably my favorite character, Nell Niblo, is actually taken straight out of a 1890s dime novel called New York Nell: The Boy-Girl Detective, which is a surprisingly good book for being 1890s trash.

That said, I don't know if I really think that ... I don't know. Did you see Gangs of New York?

Michael: Yes.

Robert: Yeah, Gangs of New York is ... I think it's a fascinating movie. I mean, if you can get past Leonardo DiCaprio's bad Irish accent and Cameron Diaz's worse Irish accent, it's a really fun movie. It is more or less historical garbage. But at the same time, it is very accurate or very true shall I say, and that it really captures a lot of the spirit of that world or at least the spirit of how people saw that world. I generally think every single thing that happens in here, with the exception of three characters that I just made up based on students of mine in the past, everything comes from the period, either history or melodrama.

The most difficult part of writing it was being an academic wanting to have all this historical detail but also knowing that I was actually writing something that people want to play for fun. So I think I tried to find some balance with it, and my goal was to have a very faithful to at least what I thought history was of the time period, even if it's ... I mean, the fiction and the stories and the melodramas of the time are part of that world, and it's part of people's imaginations at the time. I didn't really see a dividing line between the two.

Michael: Yeah, I really like that you take into account the larger, cultural, and social context of the theatre world. It's not just about what plays are produced, how much money is made. I'm curious as to why you think it's important to understand that larger, cultural, social context if we want to understand what theatre of the past was like.

Robert: That's a really good question. I'm not sure I can totally answer it because part of my impulse is to say, "I really don't care about theatre." I really care about its place in the culture and the society and what it did to people. I mean, the theatre history is fascinating and the game has very technical details about how you're going to produce a play, how you're going to advertise it and stuff like that. But I think that ... and this is possibly the result of the dominance of theatre history survey courses. If you just stay within the details of what actor did what with who and how they did it, then you miss out on the entire point of theatre, which is, like why people wanted to go see it and what impact it had on people.

And more than anything, it's that connection that I really, really longed to explore in whatever I do really.

Michael: How does this get people to engage with the history, the context, in a way that more perhaps traditional, academic approaches might not?

Robert: Well, I think, number one, the basic fact is that more people might play this then would read it if I read a book about 1849, at least I hope so. And, when I see history quite often in popular culture, media, and entertainment, I get really upset. It's generally not because, like details are wrong, right? I really don't want to bring up The Greatest Showman, which I absolutely despise and think is a vile, vile piece of work. Although I understand some people like the music and that's fine. When I started seeing that, my first thought was like, "Oh look, the pencils weren't like that in the 1840s."

But I think that we have a responsibility as historians to communicate what history ... really kind of what the nature of history is, what historical changes, and that past eras had totally different rules. I think The Greatest Showman completely flattens all social context of that time period because it wants to see Barnum as this great visionary hero. I think because it removed a lot of the social issues, race, gender, physical difference, disability, because it removed that and just made it very like now, it communicated the idea that history is just like now and you really should only focus on people like P.T. Barnum, which of course, if you know anything about P.T. Barnum, like trusting him in the slightest is a really perilous task.

So, I really wanted to ... I mean, I had to make some compromises in doing a game and that I don't think that anybody is going to respect you being a gender-neutral person in 1849 running a theatre. But at the same time, I really wanted to be able to show that something like theatre was in a very different place at the time, and that even though there's parallels to the politics of today, they were playing by different rules. I think that we have a responsibility to treat the past as something that's not immediately accessible, that's not relatable that takes some other tools to sort of access.

Michael: I'm curious if you've got any future games that you're working on, if this is something that you're going to pursue in the future.

Robert: Sure. I am currently about halfway through working on an untitled game that I can best describe as the Venerable Bede meets the X-Files, in which you play an Anglo-Saxon scribe/historian who has to investigate paranormal-ish mysteries around the year 1000. And again, it has some really hardcore historical detail, and it has a little more I guess thrown into it.

Michael: We'll post links that will let you explore the world of New York theatre in the 1840s. As well as additional information about the game, Broadway: 1849, in our show notes. Robert, thank you so much for joining us.

Robert: Thanks very much for having me. It was great.

Michael: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit HowlRound.com and follow HowlRound and @theatrehistory on Twitter and Facebook. You can also visit our website at theatrehistorypodcast.net where you can find links to all of our episodes, and You can email your questions and comments about the show to [email protected]. A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound who make this show possible. Our theme music is The Black Crook Gallop, which comes to us courtesy of the New York Public Library Libretto project and Adam Roberts. Thanks as well to Tim Kress, who designed our logo. And finally, thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Mike, the captions on the two illustrations are reversed, as I access the story on the morning of Friday, July 27th, 2018. The burning of the Bowery Theater is attached to the picture of the Astor Place Opera House, and vice versa. I'm sure this can be easily fixed.

Thank you for catching that, Peter—it's been corrected!