Women’s Leadership

Research Results and Recommendations

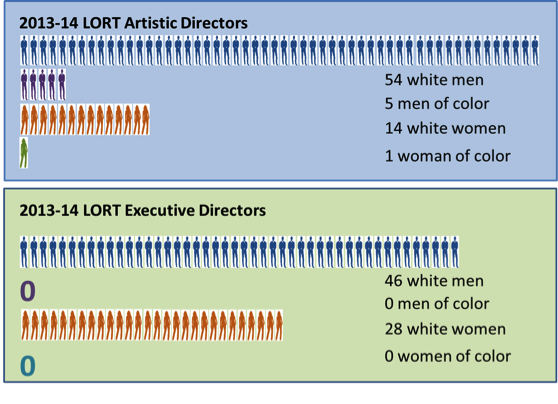

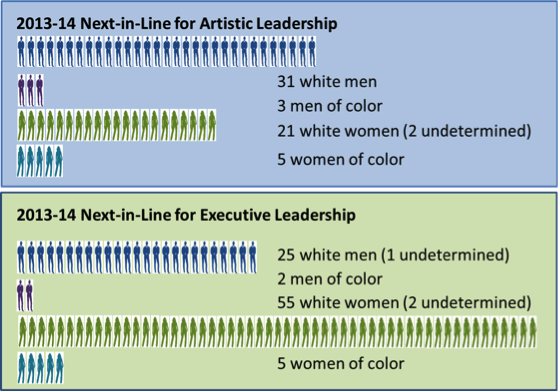

In November 2015, we reported here on our study of women’s leadership in theatres that were members of League of Resident Theatres (LORT) in the US. At the time, we wrote that women’s representation in leadership of these theatres had hovered around 25 percent for many years. In 2013–14 when we started this study there were no executive directors of color, female or male, and only 6 people of color had artistic director positions—5 men and 1 woman (see figure 1). Not much has shifted since then.

Last November, we wrote in that blog that we found both a glass ceiling and “pipeline issue” facing women in the theatre leadership. When we took a careful look at positions just below leadership within the 74 theatres in our sample however, we noticed those were occupied by a more gender-balanced group than the leadership positions (see figure 2). So, obviously, there are plenty of women on the pathway to leadership by virtue of their positions at their theatres. Additionally, when we interviewed a random group in positions immediately below leadership, we also found that the aspiration to leadership among women and men does not differ. So, no, there is no “pipeline issue” for women. Rather, as the two figures below depict clearly, we see the operation of a glass ceiling, a metaphor for the barriers facing women stuck at middle management where they can see the top but cannot reach it.

The scarcity of women and men of color at the top appears to be a reflection of both a glass ceiling and of insufficient numbers in the candidate pool hired and retained in these theatres. So, for people of color, in addition to a glass ceiling, the “pipeline” issue remains.

For detailed information about our study design, please visit our webpage.

In this blogpost we report findings of our three-year study examining why so few women hold top leadership positions in theatres and what can be done to increase their numbers. We present finding about people of color in leadership to the extent that our data sources make it possible.

Before we dig in: This is a study of positional leadership within the members of a service organization; it is not a study of LORT as a service organization. When we were commissioned by Carey Perloff and Ellen Richard to look into women leaders in theatre, we adopted the sample of LORT member-theatres because (1) we needed a limited number of theatres to research; (2) LORT members are visible because of their budget size and can therefore set an example for the field; and (3) there are resident theatres in all major regions of the country, so “location” is not a major influencing factor.

Further, efforts like ours do not stand alone. Many others have been researching and publishing about leadership diversity in theatre. See for example, Byrd, 2015; Evans, 2014; Goetschius, 2013; Jonas & Bennett, 2002; MacArthur, 2015; McGovern, 2015, 2016; Steketee & Binus, 2014; Suilebhan, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016; Weak, 2015. LORT and TCG as well have created initiatives that address diversification among their members.

A final caveat: While acknowledging that gender expression can take many forms, we worked with gender in its binary formulation of female/male, to highlight underrepresentation of a large demographic group.

What We Found: Issues that need to be addressed by the field

1. Familiarity and Trust: Findings Around Leadership Selection

Hidden behind a gender- and race-neutral job description is an expectation, grounded in a stereotype, of what a theatre leader needs to look like: white and male, because white and male leaders have been the long-standing majority of those in top positions. Expecting an artistic or executive leader to be a particular type is a subtle but strong bias when evaluating a slate of candidates. This can steer selection committees toward unconsciously or unintentionally focusing on those they had already envisioned could be trusted to do the job. This quotation from a male board member was representative of what we heard in many interviews: “Men tend to hire men because they grew up with men. Decision makers [on the board] have a business background. It’s a vestige of [whom] you are comfortable with. You’d want the best person in charge [of the theatre]. Men are more comfortable with men.” Even though theatre boards are largely gender balanced, traditional gender roles that favor men speaking and being listened to more frequently than women tend to also amplify men’s choices.

‘These boards are under tremendous pressure. You don’t want to make a mistake, you can’t be wrong in making that hiring choice...so in the end you are taking a risk, and people will take risks on people who seem most like them. And...it is no accident that they are taking the risk on all white, mostly male candidates.’ (Male AD)

Board members’ own familiarity with leadership models in business, where similar gender disparities are present, makes them more comfortable with men as leaders and unconsciously influences them to consider a man the best person to have in charge of a theatre. Below, we detail how lack of familiarity—and, directly associated with it, lack of trust—stand in the way of diversifying top leadership.

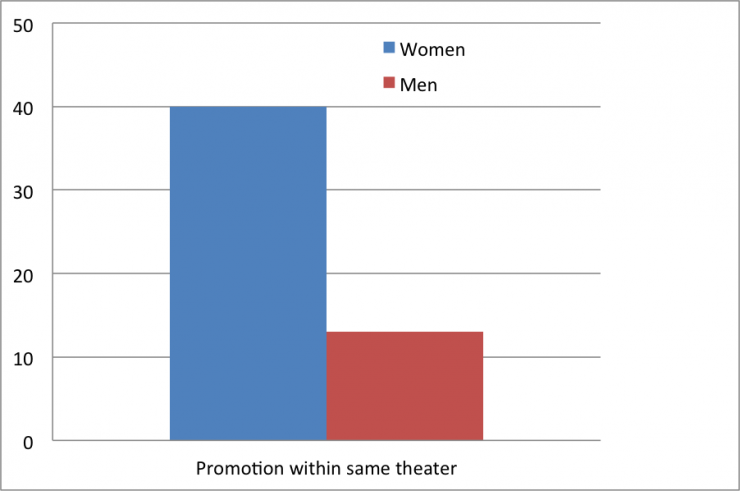

A. In general, women remain outsiders in theatre leadership, except when those who make the hiring decision know their work. In fact, women are promoted to AD positions within the theatre at which they were already employed at much higher rates than men.

In our sample we found that the only pattern in hiring preferences that favored women was that female artistic directors had been promoted into their leadership position from a lower position within their own theatre at higher rates than men (40 percent versus 13 percent). We interpret this phenomenon in the context of greater familiarity generating trust. When hiring from within the theatre, a female candidate was not an abstract, unknown entity; rather, those who made the hiring decision knew the quality of her work well and were therefore able to trust her as their candidate for leadership.

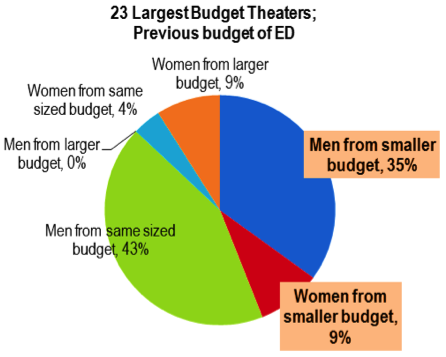

B. In the largest-budget LORT theatres (+$10 million), boards have been more likely to hire a male executive director even if he came from a smaller theatre than they have been to hire a woman with a similar smaller-budget theatre background.

Thirty-five percent of the boards of the 23 highest-budget theatres (over $10 million) trusted a man to be able to run their larger organization as the executive leader than he had before. Conversely, only 9 percent of these theatres’ boards trusted a woman to run a theatre larger than her previous place of employment. Trust in “potential” was reserved for men, especially for running high-budget theatres.

and Ineke Ceder.

C. Even though having founded a theatre is an asset, boards of the theatres in our sample showed greater willingness to hire male founders than female ones: 27 percent of male artistic directors versus 19 percent of female artistic directors had founded a theatre.

A survey of director members of Stage Directors and Choreographers Society showed that the majority of female stage directors who were or had been artistic director of a theatre arrived at that position as the theatre’s founder. That women become artistic directors of a theatre more often because they have founded the theatre suggests that women do not get selected to run theatres at the same rates as men do.

The experience one gains by founding a theatre leads to becoming familiar with most aspects of running a theatre, an experience that aligns well with the necessity of gaining wide and broad experience across departments in preparation for becoming a leader. However, selection committees for the theatres in our sample had not yet picked up on that advantage of the many women founders outside of the LORT group.

Recommendations for boards of Trustees and industry leaders for making the hiring process more inclusive:

Recognize, confront, and correct instances of gender and racial bias. If progress is to be made in diversifying leadership and attracting a full range of viable candidates, gender and racial bias must be addressed. As recommended by the consulting firm Cook Ross, anonymous surveys about experiences of bias among employees are likely to be a productive first step and should lead to addressing identified challenges.

Support greater diversity in leadership by becoming and staying conscious of common human errors in decision making, of which most people are unaware (see Nobel Laureate, Daniel Kahneman’s, Thinking, fast and slow). Take the Implicit Associations Test (IAT) to learn about biases. Biases one is not aware of can influence the hiring process starting with the decision of who sits on search committees and gets a voice, through the description of the position, to the selection of candidates to be interviewed, and ending with how candidates are assessed during the final selection steps. Ensure that in every conversation decision makers actively question themselves whether unintended biases have influenced process or outcomes.

Search process recommendations:

When a vacancy occurs, engage in a serious self-examination: what does the theatre need to change to (re)align with the mission; where has the theatre not met its goals? Do this self-examination to arrive at the skills and experiences that the theatre needs to include in the job description for the next leader to better meet its goals.

Ensure search committee membership is diverse. The committee chair needs to guarantee not only that diverse voices are present but that they are heard and respected. Decision making by unanimous agreement is recommended because research suggests it can amplify women’s voices and their authority in ways that “majority rule” does not.

Conduct an external search—which also allows internal candidates to apply—for major leadership positions. These offer an opportunity for board search committees to consider the widest view of the candidate pool, and expose them to candidates whom they may not yet know personally.

Give serious consideration to the intention behind the Rooney Rule, which saw its origins in American football where the racial backgrounds of head coaches and players were vastly unbalanced (70 percent black players versus 6 percent black coaches), until conscious changes in hiring practices were sought. The Rule generally refers to having candidates from underrepresented backgrounds among those who will be interviewed for an open position. Interview several applicants from an underrepresented group when there is a vacancy. Make it a routine practice to review a search firm’s track record of placing diverse candidates in similar positions before hiring a search firm. Insist on diverse candidates in the slates that are presented.

Evaluate a slate of candidates for whom personal and demographic characteristics have been disguised (“blinded”) when selecting whom to interview, so as not to be influenced by characteristics irrelevant to doing the job.

When interviewing candidates for an artistic director position, look for skill and enthusiasm for speaking in front of a variety of large and small groups, relationship building skills, and willingness to support development efforts, which are key components of fundraising responsibilities for artistic directors instead of emphasizing actual fundraising experience.

Pause, when you are about to make a selection, to slowly and deliberately evaluate that the choice is not based on familiarity, comfort, and implicit trust of what is known but rather that it is justified on the basis of the theatre’s identified needs and the candidate’s ability to meet those needs.

Provide support to the theatre’s leadership team during a period of transition to a new leader.

Develop explicit criteria for vetting leadership candidates. Industry leaders should discuss and arrive at the expected level of competence required of all theatre leaders.

These criteria can be the focus of a leadership institute for high-level managers who aspire to top leadership positions.

Service organizations such as LORT or TCG can take the lead in organizing field-wide conversations (where diverse voices are solicited and heard) on job requirements for artistic and executive directors and how candidates should be scored on each job element.

When there is a vacancy, a theatre can work with those newly created field guidelines and emphasize those that emerge from its self-examination of what it needs from a candidate to move forward on the theatre’s mission at the time the vacancy has occurred.

2. Work-Life Balance

Requirements for a successful life in the theatre (which may include extensive travel, and long and irregular hours) can be barriers to participation for caregivers (who are mostly women) and more importantly operate as hidden biases, which quietly affect the hiring or promotion process.

Despite the plethora of loud voices in blogs and during conferences on the need to address balancing family responsibilities with a theatre career, our interviews with leaders of LORT member-theatres were relatively silent on how having a family may have affected their career paths. Similarly quiet on this topic were our surveys of directors and high-level managers throughout the US theatre field. Not able to interpret this contradiction, we probed deeper into the topic in conversations with industry leaders. They made it clear that a woman would never bring up family responsibilities for fear of not being given the same benefit of the doubt that she would be able to continue her career as her male colleague who is presumed to have someone at home taking care of the family.

“Women are trained, at least in my field, to shut up when they have children, because it is a liability. You won’t get the job!” (Female AD)

Recommendations that address work-life balance issues for caregivers:

Open up family responsibilities and work-life balance topics for conversations both at leadership and other levels of responsibility without questioning employees’ and candidates’ professional commitment or availability to do their job.

Through consciously instituting and advertising family-friendly policies, theatres can bring the subject of family-life balance into the open, and inspire others and the whole field to adopt policies that benefit, support, and retain qualified employees.

Create new or offer better and affordable childcare options for staff, and extend them to visiting directors. Models are available in industry and academia where on-site day care may be available for those who need it. Alternatively, theatres can recommend vetted local programs and negotiate with those programs admission for (temporary) care of (visiting) artists’ children; provide additional accommodations for visiting artists’ caretakers without considering this an extra burden; and provide these accommodations to both male and female (visiting) artists.

Put in place a more objective selection process at every level of responsibility where selection criteria are clearly spelled out and equally applied to each candidate. When a placement has been finalized, work-life balance should be put on the table explicitly to build a safety net around the new hire’s needs in order to fully support her/his chances at success.

Include an open conversation with each employee about the work-life balance support in annual review sessions.

3. Culture Fit

Simply hiring people who have remained outside of theatre leadership will not guarantee that diversity will be achieved, as indicated in this comment: “I think the worst thing any artist of color could do right now would be take an artistic directorship at an institution that’s not a good fit and fail, because every failure for one is one that everyone pays for for ten years” (Female next-in-line). We heard comments in interviews such as, “there isn’t as much room for strong women who are not lowering their voices” (Female next-in-line) and “[my mentor] didn’t seem to think that black directors could direct anything other than black work” (Female next-in-line). Success in diversifying leadership along gender identity or expression, race/ethnicity, physical ability, sexual orientation, and class background may require making adjustments to the prevailing cultures of many theatres.

Recommendations that address making a theatre more inclusive:

Address how the theatre can attain a supportive cultural fit between the theatre’s dominant culture and an employee’s individual culture. It is imperative to start conversations with the dominant and the individual culture on equal footing when striving for adjustments without pushing the dominant culture to be the default for success.

Provide a safe space for discussion of differences. Train human resources employees to be receptive to concerns of unconscious bias or discrimination and bring in outside experts to lead workshops about this topic.

Deliberately discuss retention efforts for a non-traditional employee or leader. Discuss how the organizational culture can adapt its “practice as usual” to be more welcoming to and supportive of diversity in hiring and retention.

(if leadership is diversified) “They’re afraid that programming will shift so radically that it will distance the long-time subscriber that may or may not be as interested in more diverse programming, or funders—which I think is even the bigger issue—going, ‘Well, you know, this funder might not be comfortable….’” (Male AD)

4. Mentoring

Career progression in the theatre has traditionally been based on the apprenticeship model. People who aspire to leadership positions told us they want mentors who “look like them,” who have had similar experiences. For example they seek mentors who can understand the challenges of juggling family responsibilities, or who can speak to the challenges faced by people of color in a field that has predominantly seen white leaders.

Mentors can help flesh out the variety of experiences an aspiring leader needs in order to become a viable candidate and provide more clarity about career progression which many people below top leadership told us was unclear.

Well-positioned, aspiring leaders identified specific areas for needed growth:

For artistic director positions: Directing at a variety of theatres, public speaking and relationship building skills to apply during fundraising efforts, and experience producing shows are important for building their reputation. Directors of color need invitations to direct widely, beyond the works of playwrights of color.

For executive director positions: Fundraising, board relations, strategic planning, and cross-departmental expertise are needed.

Mentors can also promote their protégées to search firms and search committees who rely on these personal endorsements.

Short of a mentoring relationship, which involves a committed and personal relationship, sponsorship is also very valuable coming from well-respected theatre professionals who can champion a candidate’s qualifications with other leaders or with a search committee.

“I would love to have a female AD mentor. And I feel like I could grow in leaps and bounds if I had someone who wanted to be challenged on their assumptions.” (Female next-in-line)

Recommendations around mentoring:

What can mentors/sponsors do?

Talk up a protégée’s qualifications to enhance their visibility.

Give time and attention to a direct report’s career development even if there are not enough resources to serve as a full-fledged mentor. Every relationship, even a casual one, can promote career growth.

Promote relationships and networks for aspiring leaders as a deliberate and routinely practiced sponsorship activity with search firms, board members, philanthropists, and other influential people.

Support skill development by assigning manageable-sized tasks to people who are exploring a leadership path. Provide guidance but let them do the task from start to finish. If the task fails, mentors can help the person learn from the failed outcome; if it succeeds, mentors can help publicize it.

Invite aspiring leaders to sit in on meetings of departments whose functioning they need to learn more about. On the other hand, dispel the myth that a professional has to have mastered ALL relevant skills before becoming a viable candidate.

Introduce protégées to board members, and invite them to attend board meetings.

Include conversations about how one develops a career in the theatre with every annual review. These conversations should also include particulars about the realities of career progression both within and outside of the protégées’ theatre. Offer emerging leaders who have reached the stage of becoming candidates the opportunity to do practice “mock interviews.”

Recommendations specific to the artistic side:

Promote female directors’ opportunities to direct plays at a variety of theatres so that they can build networks of artists who can speak to the breadth and depth of their directing experience and leadership potential.

Promote directors’ of color opportunities to direct a variety of plays beyond works by playwrights of color so that they can expand their portfolio and build networks of artists who can speak to the breadth and depth of their directing experience and leadership potential.

Demystify fundraising responsibilities of artistic directors by stressing that they primarily entail relationship building and presentation skills as the public face of the theatre. Provide a variety of and frequent practice opportunities. Provide guided opportunities to witness and practice interaction with high potential donors so that aspiring leaders can in turn deepen their own relationships with them.

Provide experiences of producing plays, or mentor in key skills related to producing.

Recommendations specific to the managerial side:

In addition to board exposure, offer opportunities for attaining cross-departmental expertise, including producing. Provide set-aside time to achieve these.

Translate “strategic planning” as planning for the future in the context of a theatre’s mission and values in order to make it less intimidating as a topic. Provide time to participate.

What can aspiring leaders do?

Seek out several people who can serve varying mentoring functions. Mentors have different strengths, and can provide different types of support and guidance.

Initiate projects and recruit more senior people either inside or outside of their own theatre to receive “hands off” guidance to accumulate accomplishments they can highlight in their resumes.

Cultivate a large network of relationships, including relationships with peers. Even if none of them become a strong mentoring relationship, these relationships are still valuable for career progression.

Cultivate relationships with search firms. Ask specific questions that can help guide growth.

Seek out board experience by serving on the board of other organizations.

Look for opportunities to do practice “mock interviews” with seasoned leaders.

5. Affordabiliy

Many aspiring leaders are part of an emerging generation of ambitious young people who have acquired substantial student loans for attending college and graduate school in their drive to progress through the ranks toward leadership. For them, affordability of a life in the theatre is an important and sometimes limiting barrier.

Recommendations addressing the cost of starting a life in the theatre:

Offer aspiring leaders training built on the most successful graduate training programs’ models through paid internships and apprenticeships to make it possible for them to acquire skills and networking opportunities without the high cost of a graduate degree.

Enter conversations with state and federal government to increase funding for the arts and introduce a jobs program that includes paid work at theatres or other arts institutions.

Ultimately, the survival of regional theatres may depend on diversifying leadership, boards of trustees, and audiences. The targeted outcome of this work is to balance the playing field to theatre leadership in a focused manner. We hope you will join the conversation and efforts toward this outcome. On Monday, August 22, you can witness, via HowlRound TV livestream, a presentation of our work, and the feedback from several thought leaders. We hope you will tune in and participate in making strides forward together.

For more information on this project, you can find the full executive summary here.

For more info about the HowlRound TV livestream, and to tune in, go here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

It is critical that the criteria for positions begin to value and language descriptions that include how female identified colleagues work in the field differently than our male-identified counterparts. Currently, when applying for a job, we pretzel ourselves into a job posting that is created through the lens of a white and male-identified normative. The search firms and boards base the interviews on this criteria. Before our applications are even sent, we are then challenged to meet a criteria that never took female-identified candidates into consideration.

My approach to leadership and my relationship to the art and art-making in conjunction with my management style is greatly informed by my processes of how I nurture, bring along, and deepen my relationships and building of community. These values and approaches will save our institutions.

Thank you for this clear and concise summary of the well-designed research and incisive thinking you have done about women's leadership of resident theatres. Having read and provided feedback on both the full report and the executive summary, I know how thorough your research has been and how responsive you have been to the thoughts of numerous field leaders along the way. I look forward to viewing today's presentation via HowlRound. I hope it leads to more constructive conversation and the changes needed to provide greater equity and inclusion in the hiring of theatre leaders.

Excellent article. My comment is on affordability. I have encountered several situations where the hiring theatre requires a Masters degree with a very narrow focus (think "Arts Management"). Since advanced degrees cost quite a bit of money these days, if they stipulate such a requirement, theatres should be willing to pay an income that allows recently graduated students to afford both to live at a decent level AND pay down their student loans. Too often, I have seen theatres that require advanced degrees but don't want to recompense their workers an income in line with the financial investment that applicants put in to earn the required educational qualifications.

Thank you for citing 'Not Even' my report on gender parity of SF Bay Area directors, playwrights and actors. I am looking forward to tomorrow's conference at ACT and hearing more!