An Interview with 7 Fingers’ Gypsy Snider and Shana Carroll

P. Carl: I know you both have a history with the circus and families connected to the circus. How did that history shape your idea of theatre and art in general?

Gypsy Snider: I was raised in a time of traditional circus. The Pickle Family Circus was trying to do something alternative and trying to do something contemporary, but it was much more in relation to what was around us, which was a very traditional circus world. All the shows had animals and sequined girls and fishnets and sawdust and the whole shebang. I think that my parents were interested in doing something that was going to touch people on an emotional level, to really communicate with people, to empower people. They were also really interested in music; there was an incredible five-piece jazz band, and my stepfather was a clown and a comedic juggler, and had a great sense of theatricality, and musicality. My mother came from more of a theatre background—she studied to be a set designer.

On the one hand, growing up in the circus, I came from a much more traditional sense of presenting tricks and getting people excited about what they were seeing, but I think that my parents were also really excited about the possibility of more. I pull from traditional circus a lot, and yet I was very fortunate to be influenced from a very young age by many, many forms—music, clowning, theatre, physical theatre, and then at some point by stage acting. I didn’t do any film, but I was a huge film fanatic. I think one of the things that makes 7 Fingers different from many of the other contemporary circuses is that we do have a strong connection to traditional circus, or an appreciation. When we construct an act, we’re thinking “I’m not going to put the best trick first because I want to save it for the end.” Or “I want to put the best trick first because then we have people at the edge of their seats from the moment we start.” That’s what they do at Ringling Brothers.

I think that my parents were interested in doing something that was going to touch people on an emotional level, to really communicate with people, to empower people.

Shana Carroll: There is obviously a lot of overlap with Gypsy and me—we’ve known each other since we were fifteen. I started in theatre, I didn’t really start circus until I was eighteen. I grew up doing theatre fairly seriously for a child and teenager, doing Shakespeare summers and arts camps and directing when I was seventeen at my drama studio—things like that. I didn’t really have any kind of athletic background and didn’t know circus at all, and didn’t have an interest. My father became very close with Gypsy’s parents because he wrote the 10th Anniversary book of the Pickle Family Circus—he fell in love with the company. He encouraged me to get involved as a day job. At eighteen, I also fell in love with it. My love of circus came from my love of theatre; how it was a way of telling stories and the beauty and the metaphors and the dance element, and not the athletic element that a lot of circus performers are drawn to. My knowledge of circus came through Gypsy. She was my first coach, and my first friend in the circus world, and she imparted to me all of the philosophies behind traditional circus. The other thing I would say about the Pickles was that it was also community-based, coming out of the seventies—it wasn’t really touching people onstage the way an artist can, but really going in and transforming communities. That’s also true of traditional circus—we’re not active in a community the way they were, but I think the circus family feeling is there in the way we create shows.

Carl: You’re at this moment where you’re evolving the notion of circus; you’re managing to transcend the boundaries around circus. You have a show on Broadway, you have a dinner show, and you seem like you’re inventing what circus means. I wonder if you might talk about where you are in that evolution.

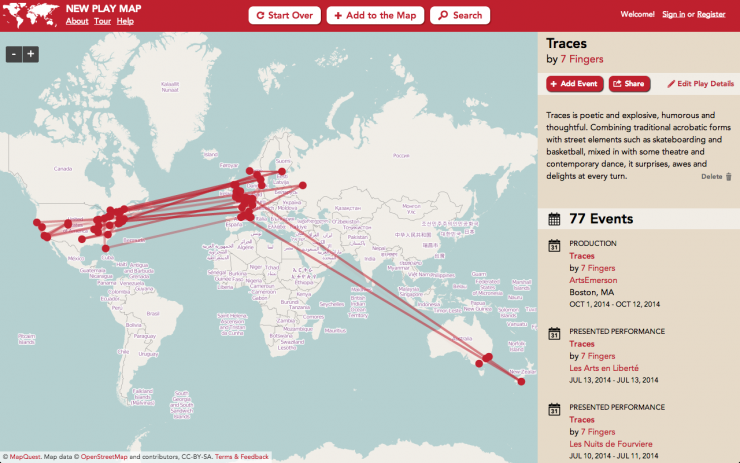

Gypsy: I’m most excited about the company right now. I really feel like the sky’s the limit, and we get to try and reinvent ourselves with every project. Of course there’s a little bit more of an expectation now, which is sometimes daunting, but when I go see Shana’s project, Queen of the Night, I know this work so well, but I’m also completely surprised and ignited and enthralled. Then you go around the block and you’re at Pippin and that is totally different. Then you go see Pat’s [Patrick Léonard] show, his one-man sort of tragic clown show, and it’s so funny. I love that there’s a certain sense of humanity in all three of those productions and yet they’re all completely different. The common thread between these three pieces is that the circus transforms the people that see it in some way. That’s our through-line for all of our shows. When we did Traces, there was nothing like that anywhere. People were shocked and somewhat distraught—“you can’t do it that way.” It was stressful for Shana and me to say, well, why not? It felt so right to us, so organic and real. Having the acrobats speak nonchalantly to the audience about themselves was everything that Shana and I love about theatre and circus. But it was really shocking for a lot of people. So when we go and make circus work in a form where it’s never existed before, these very painful steps into the unknown, and once they’re born, I couldn’t be more proud.

Shana: I would add that circus is kind of on the brink of being considered an art form. This is a form where you can tell a story and express emotions and be a mode of expression that can be surprising because the audience is not expecting to be moved and have stories told to them. On the other hand, there’s still the close-mindedness, it’s not globally recognized, and it’s still a struggle. We still run into that, even with people when we collaborate, there’s this idea of what circus can function as and not function as. For us, it’s our form, so we feel like it’s limitless, because you can tell any story with circus.

Gypsy: I feel like people are still finding it hard to accept or understand that an acrobat can actually advance the story. People think, but it’s tricks, it’s just tricks. But when you’re watching it, aren’t you stimulated and moving forward in terms of your relationship with the acrobat and his energy and his emotion? Then it becomes an intellectual conversation for which most people in theatre and producers don’t have a vocabulary.

Carl: I want you to say more about that—this issue of story. You are really trying to do two things simultaneously and that’s part of the evolution, or at least that’s been my experience of your work. You’re doing the things we expect—the virtuosity, the acrobatics—but you’re also really saying something about the world with the stories you’re trying to tell.

Shana: An acrobatic trick can be a plot point; it can have its own dramatic arc. Quite often acrobatic tricks are performed as demonstrations and are meant to be impressive, but in fact a very emotional reaction is generated when you see someone plummet into the air and be caught at the last minute. We’re transported in a way that is a dramatic moment when it’s used as part of that dramatic arc, the way in a musical when a performer breaks out into song. When it’s done well, you feel the emotion of that moment, the performer had to break out into song, that was the only way they could really communicate that emotion, normal text would not do it. Different circus elements correspond to certain metaphors and language—aerial has a very clear metaphor of reaching higher and being trapped between earth and sky. If you know how to use those images and incorporate them in your story, or to take the essence of that circus act and build the story around it—which is something that we do a lot as well. We often create two halves of a shell—circus performers tend to individuate, they are not trained to be a dancer who dances in every style or an actor who can play any role—circus performers are trained to find their own thing. The best way to use them is to figure out their particular kind of beauty and genius and create a concept out of that. The other half of the shell is the different ideas, themes, and issues that concern us as creators or directions we want to go in, and then figuring out how the two halves come together and create one concept. We work on the parallel tracks, and I think it actually gets this great, organic result, but it’s a very different process than a normal, scripted show.

Gypsy: I also think just having finished Pippin, the touring cast, it’s so amazing how a musical achieves what Shana was talking about, how the emotion becomes so intense and forthcoming that you have to sing. But what I did realize is that they are still bound by these words, and that it’s still very explanatory. The movement and the limitlessness of the vocabulary you can find in circus and the imagery is so strong, that for me, I feel the words are there. A lot of people get stuck on what’s happening, what are you doing, and I think that that limits their capacity to recommunicate what is actually seen.

Carl: Musicals do it in a different way, but you’re actually creating a new way of telling stories.

Shana: Circus, even traditional circus, by nature is sort of mixed media. Juggling and wire-walking and clowning are incredibly different forms. Clowning is theatrein a sense, and juggling is a very particular skill that has to do with manipulating objects, but it’s not one that’s necessarily risk-taking—they’re just such different skills. Already in the nature of circus there’s this out of the box, out of category approach to it, so it was very easy to move into more contemporary circus, into actual theatre and not traditional clowning, and actual contemporary dance and not just traditional acrobatic choreography, or even multimedia and video—all those things already seem more natural to circus because the doors are already open.

Carl: How important is the city of Montreal for you since Montreal has created a circus district? How has that impacted your work and your identity?

Shana: I have a theory that circus really thrived here because one, when you live in Montreal the language is politically charged here, it is a bilingual city in some ways. So actual spoken theatre, tends to isolate one audience or another. I think as a result physical and abstract forms, like contemporary dance really thrived here. Street performance had to be much more about being physical than about using anything spoken. Quebec also didn’t have much of a circus tradition, and as opposed to having that weight of tradition—like in France the contemporary circus is really a movement against traditional circus. Then something happened in Quebec, where the people who discovered circus in the eighties and the Cirque du Soleil people and the people who founded the National Circus School here—came up with a new way of expressing themselves. That really set the groundwork for the entire approach to circus in Montreal.

Quebec also didn’t have much of a circus tradition, and as opposed to having that weight of tradition—like in France the contemporary circus is really a movement against traditional circus.

Gypsy: I would go as far as to say one of the reasons why I came here was because I thought from a very young age that to do creative things in the United States, you had to be incredibly spectacular and famous. It really turned me off at a very young age.

Shana: Art is a hard thing to saddle, and for whatever reason, the way circus evolved here, now we’re acknowledged by the provincial government as an art form that can get funding, and we’re treated the way the dance companies and the theatre companies are treated.

Gypsy: One of the wonderful luxuries of working in New York is I love being part of that whole whirlwind of the entertainment world and culture, but I do feel ever so grateful every single time I can leave, because you can feel trapped in it. You feel like you’re working in a machine that is so demanding and so excellent, and you have to prove yourself all the time with everything you do. What I love is that I go out and do something, let’s make this incredible, but then I can also leave and take perspective and freedom to look at what I really want to say, not just at this group of producers and creators, and the machine of the art world.

Shana: I remember hearing once about Hollywood, how it just costs so much to make movies that in fact they can take fewer and fewer risks. I think to a certain extent, as amazing as Broadway shows are, there’s very little creating shows from a blank page.

Gypsy: What I love with our company too, is that even with the pressure now, we can still try things, we can really fail and tweak and it doesn’t matter because we also have other things, we also have Traces still going. And the only way for us to plan is to try things.

Carl: I love that the city is almost the hub for the infrastructure of your imaginations in a way. When we were having our conversation about Traces coming to ArtsEmerson, you said something and I’ve been thinking about the risk of circus and the life and death business of it, and the way that the risk creates an opening for human connection. I wonder if either of you can expand on that a little bit.

Shana: Two of our artists were training in teeter-board and in the middle of training, the board broke. He was propelled off to the side, and it was one of those crazy situations where just two seconds before we had decided to put a mat there for some choreography—normally in teeter-board you don’t go off to the side. Yesterday I had a complete moment of remembering where you have to come back to earth and the fragility of what we do. When I was eighteen and deciding to do circus, I was involved in a form where you take a risk on a daily basis. I became a trapeze artist. I think that when you take a risk in one corner of your life, it transfers over and makes you more courageous in the rest of your life. There is something life-affirming and empowering, where people are taking risks regularly, and I do think it is healing in a way. I think it’s true that as a spectator to be able to watch something that is choreographic and beautiful and to be transported to a place where you see someone risking their lives in order to do it, and the stakes are that high, it produces an emotional response you can’t achieve in other forms.

Gypsy: It’s really the essence of Traces—you have these seven people and they’re living an intensified version of how we’re all living. Their time is limited, our time is limited, and how far are we willing to go to live that life fully? Isn’t that what our entire lives are about—loving the people around us as much as we can? Giving ourselves to our lives and our communities and our families as much as we humanly can before it’s taken away from us? It’s the whole reason we do art. I think of it as the essence of why we do performing arts, this idea of “I want to share my innermost self with you, with my whole body and soul.” It almost sounds cheesy when you say it, and yet when you use it for performance, the overwhelming reaction that you get from the audience is that these performers surprise me from the most simple to their most complex feeling in the course of an hour.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here