The craft of theatre can and should be deeply collaborative, but the artmaking of theatre and the collaboration of theatre must be acknowledged as two distinct processes that, while happening simultaneously, should be tended to in different ways. I was lucky enough to observe and home in on that specific dynamic while also being a part of it as a participant of the 2023 Latinx Theatre Commons Designer and Director Colaboratorio. The team I was a part of consisted of Luis Manuel Garcia (lighting design), Miranda Gonzalez (director), Laura Moreno (costume design), Noel Nichols (sound design), Frank J. Oliva (scenic design), and me, Mateo Hernandez, as the scholar/documentarian or “process guide/facilitator.” Of course, a part of my role was to document the process of our particular group and report about it via this essay, but in the room, we discovered another aspect of how I could operate as a member on this team, which colors the way I frame this essay. During our time working together as a team, I observed not only an incredibly talented, smart group of theatremakers getting into the artistic minutiae of designing a production, but also a beautifully nuanced collaboration process that, though it very much informed the artmaking, was still different from the artmaking process. I argue that a larger awareness of the labor that specifically tends to collaboration is needed across theatremaking spaces to distinguish the labor and process of collaboration from the labor and process of the artmaking.

How Do We Tend to Collaboration?

Noel Nichols, Frank J. Oliva, Laura Moreno, Miranda Gonzalez, Luis Manuel Garcia, and Mateo Hernandez at the LTC Designer and Director Colaboratorio. Photo by Roy Arauz.

The director in our group, Miranda Gonzalez, is an expert facilitator and engaged the room from early in the week with a series of open-ended questions that helped her and everyone in the room really get to know each other. They included: what do you need in spaces that you usually don’t get? What do we want out of this experience? What kind of theatre do you want to make forever? When do you know that the design or technical elements of a production are not great? In what ways can design be elevated? I share these questions (with Miranda’s permission) as a means of letting you in on a bit of our process and so that you might use them in one of your own production processes.

These questions helped us identify the values everyone in the room shared and develop a real sense of community and trust with our collaborators. The first question, “What do you need in spaces that you usually don’t get?” elicited responses from group members about their oppressive and oftentimes traumatic experiences working particularly in predominantly white institutions (PWIs). These instances of unfortunately similar experiences as Latinx folks created a sense of belonging together in the space as well as a commitment to not reinforce those oppressive ways of working with one another. Then, questions like, “What kind of theatre do you want to make forever? When do you know that the design or technical elements are not great?” revealed our shared values of theatremaking. We were all interested in creating theatre that is uniquely live and makes people feel something, as well as a design that has a conceptual continuity across the production. We gave ourselves the time each of these questions needed and felt no rush to get to the actual designing process of the play we were given; but when we did get there at the end of day two, we had a solid design concept in a matter of just ninety minutes!

As we gave ourselves permission to be in space with each other without the pressure of a final product, some beautiful moments of learning from each other happened.

Through our time together answering those questions Miranda posed, we were not only identifying shared values but also how each of us operates in a conversation- or collaboration-type space. The energy in the room on the first day of working together felt like an engine that was slowly revving up, stopping, and starting—folks trying to find their place in the dynamic of this specific group, some taking bold risks, and ultimately getting into a steady rhythm through which folks were operating closer to their true selves. As the days progressed, and especially during our design sessions, the energy of the room (to continue the engine metaphor) was buzzing, quick, efficient. Ideas fired from one person to another. Folks were operating in the way they knew they needed to and felt safe in the room to speak up and step back as the needs of the group shifted. Because of the groundwork we laid for collaboration with the stories and values we shared, we were able to design the production in this electric kind of way in which folks knew who to turn to for what, how to be in space with each other, and why we were making the choices we were making (or, when we didn’t know, we were not afraid to ask each other why).

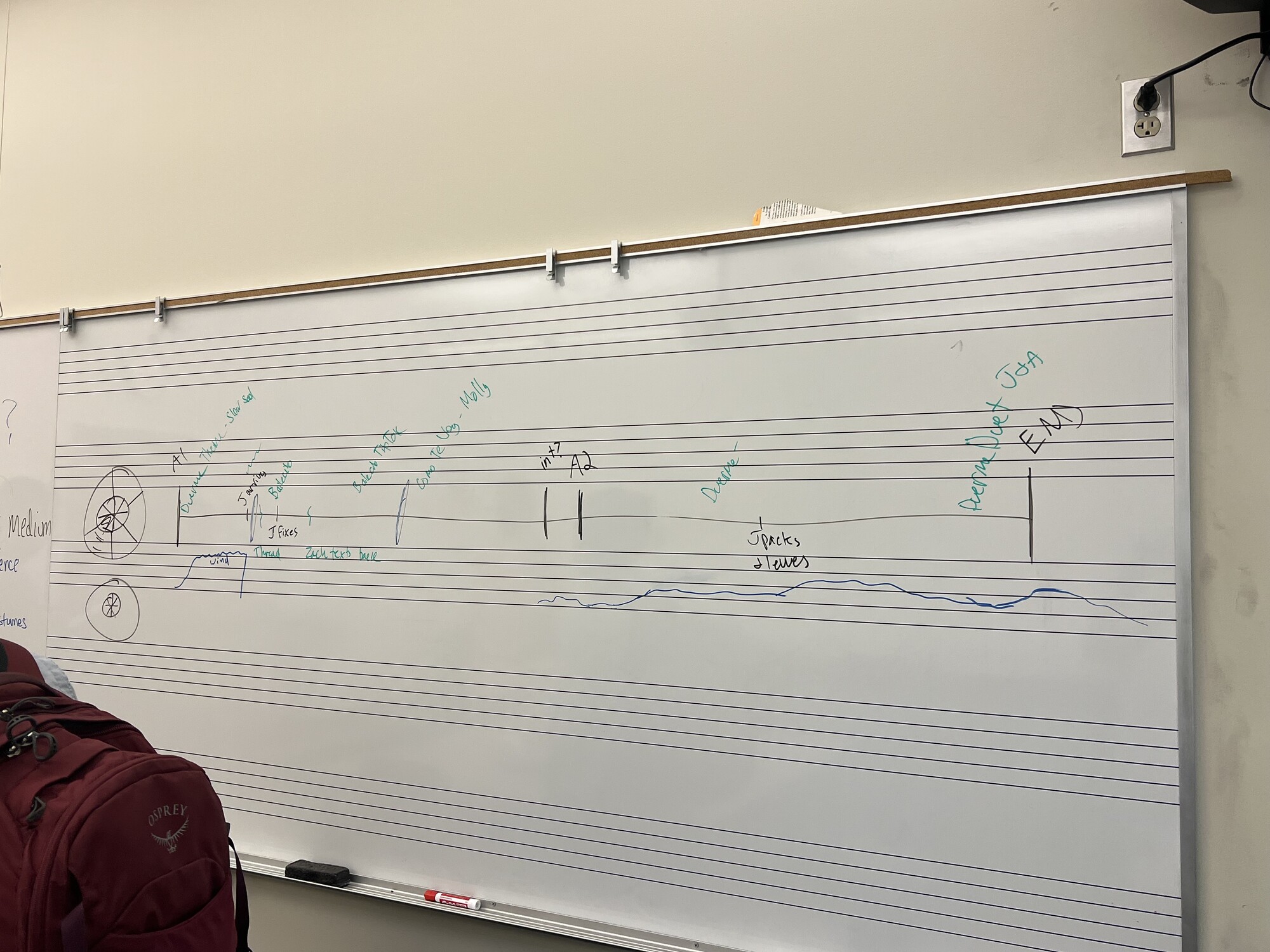

As we gave ourselves permission to be in space with each other without the pressure of a final product, some beautiful moments of learning from each other happened. Two were particularly resonant, the first being Noel’s visual sound map. During our time getting to know each other, Noel shared one of the key ways she thinks about sound design through a visual sound map she drew on the whiteboard in our room. The map is a way to lay out the sound of the entire production and how music, audio effects, speaking, and silence play with each other to create the aural experience of a play. I felt so lucky to learn this from Noel in that moment, as did everyone in the room. We were all rabidly taking notes and capturing photos of the map drawn on the whiteboard. As artists, particularly designers and directors, seeing something as ephemeral as sound laid out in a visual way helped us all to imagine the full scope of the play and how each design element can work within that aural landscape.

Noel Nichols’ sound map. Photo by Laura Moreno.

Another beautiful moment of learning, amongst so many others, was when Laura admitted her own insecurities with other design elements and how that has caused her to feel lost and become unable to communicate effectively in some instances during past design processes. She expressed gratitude for being able to learn more about the other design disciplines through this Colaboratorio process, and others in the group admitted how much they learn from other designers while working in production processes outside of Colaboratorio. While some production processes may cultivate this kind of co-learning environment, Colaboratorio was a specific process to engage in those vulnerable questions and learnings. I believe this moment of vulnerability taught the group that honesty and transparency with your collaborators is so vital to building trust and creating a better production.

Along with our shared values, trust really was a feeling we cultivated in our group’s work. One testament to that trust is our lack of setting group agreements with one another. On our third day of working together Miranda began by expressing regret for not beginning our process on day one with group agreements, which all of us responded to with grace and reflection. This moment gave us all the chance to reflect on our own previous experience with and use of group agreements. Laura noted that sometimes these rules can feel like they are placed on you rather than cultivated from the values of the group. Noel noted that all of us are educators or facilitators in some capacity, so we knew instinctively some of the basic ways we might want to share space together. Then, Frank shared an insightful experience he had while facilitating a group of Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) folks where they felt that group agreements were not needed as urgently when in this kind of affinity space. Luis (who could not join us until the very end of the first day) spoke to the vibration of the room that he walked into, which felt inviting and like a place he wanted to be. I share this moment of reflection we had together not to condemn the use of group agreements—I personally use them as an educator in practically every space I facilitate—but because it is productive to think about how those agreements can and have been appropriated and even weaponized in some spaces to achieve the exact opposite of a safer space for BIPOC folks.

Miranda Gonzalez, Frank J. Oliva, Noel Nichols, Laura Moreno, and Mateo Hernandez at the LTC Designer and Director Colaboratorio. Photo by Roy Arauz.

In the kind of affinity space we had created, with shared values identified through storytelling and trust building, the need for those agreements dissolved because we felt somatically how to be in good relation with each other as well as what it felt like to be safe in our bodies and experience. I see our disuse of group agreements as a transgressive act—not establishing ourselves in space in this prescribed, neoliberal kind of way, but rather by feeling in our bodies the safety and trust we were jointly building and investing our energy in the relationships with our collaborators in the room. There are, of course, many ways to achieve this kind of space making, and I urge you to find what works best for your group given the values, identifies, and goals present in the room.

Finally, I return to my given/chosen title of “process guide/facilitator” (which was brainstormed together within our group) and how that role might be integral to the way you and your collaborators work together. As someone who was both in the process and observing the process, I was able to document the way the collaborative process was operating and offer questions or prompts to guide that process along without stifling the artistic process. I did so by reflecting back what I was observing in the room as it pertains to the way we were collaborating, offering open-ended questions for more expansive conceptual conversations, and sharing some of the logistical realities of the process we were working within, all with an objective of creating a more honest and vulnerable collaborative space.

We don’t necessarily have to radically reimagine a collaborative process; we can lean into our shared values and commitments to change and trust that our work is imaginative, groundbreaking, and transformative.

A key observation I made was that we don’t necessarily have to radically reimagine a collaborative process; we can lean into our shared values and commitments to change and trust that our work is imaginative, groundbreaking, and transformative. By being aware of how to be a good collaborator while simultaneously doing your theatremaking, you can cultivate a collaborative space that is seamless, pleasurable, and process-oriented while also producing a great production in the end. So, how will you think through your collaborative process as well as the artistic process in which you are about to endeavor? How will you tend to both of those as needed? What can you and your team do now to cultivate good collaboration in conjunction with the great theatre making you are about to achieve?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here