I've always hated Evita, the 1978´s musical by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. I end up deeply offended, not only because productions of it don’t always employ Argentinians or South Americans (please don´t get me started on the movie), but because it flattens the complexities and ambiguities of Peronism and Eva Duarte. And I take it personally: I am a Peruvian living in the United States, and a considerable part of my everyday life I ask myself how are others seeing me? It has become a second nature. That question shapes every interaction I have. Do they see me as a suffering queer from the third world, born in civil war and raised in dictatorship? Or as a light-skinned Latine who doesn´t understand oppression and racism? As a Yale student, am I secretly wealthy? (I´m not.) Does my bald head speak of my experience, or does being in school in my thirties means I “didn´t make it”? These questions danced on my flesh as I watched Maia Novi´s first play, Invasive Species, directed by Michael Breslin at the Tank in July 2023.

Negotiating the Migrant Self in Maia Novi’s Invasive Species

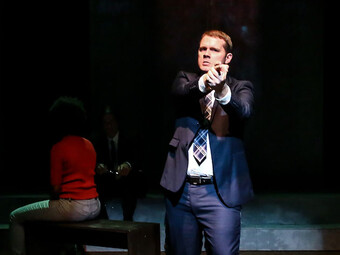

Sam Gonzalez, Julian Sanchez, Maia Novi, Raffaella Donatich, and Alexandra Maurice in Invasive Species by Maia Novi at the the Tank. Directed by Michael Breslin. Lighting design by Yichen Zhou. Sound design and composition by Jessie Char and Maxwell Neely-Cohen. Dramaturgy by Amauta Marston-Firmino. Photo by Maria Lutteal.

Invasive Species is a testimonial play, a mode of documentary theatre wherein the performers share stories of their lives with the audience members, who accept a pact of truth: we believe the body on stage is telling us what actually happened outside of the theatre. They can be lying to us (artists like Marina Otero and Sergio Blanco have mastered the art of bullshitting the audience with their consent and enthusiasm), but during the time we are breathing the same air, we´ll suspend our disbelief and fully trust the confessions of the performer. And so Maia begins by taking us to a movie theatre in her native Buenos Aires, Argentina. She watches The Amazing Spider-Man, fascinated at the colors and joy and bloom that the United States promises. She decides to go through the screen to see this land for herself. This resonates with me: I remember being a kid in the nineties, when my dad brought us chocolates from California. Snickers, M&M’s, and Three Musketeers tasted as if they came from a faraway heaven. It is funny, today I can´t eat any of them. But if you bring me a Turrón de Doña Pepa from Perú, I´ll be your best friend.

On stage, Maia moves to the States to study acting in grad school. Her work doesn´t allow her to pay her bills in Argentina, a country still in economic distress, and, well, her parents are a bit too dramatic for their own sake (both brilliantly played by Sam Gonzalez). We grew up in countries in the verge of falling apart, so shows like Full House or The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air promised that some peace could be found in the United States (I´d say Jac Schaeffer´s WandaVision explores this brilliantly). Once in the States, however, Maia finds she can´t fit in in the new country. The Americans of the North dissect her presence, turning her body into something familiar: she is told that she looks the parts she wants to play, but she doesn´t sound as she should. Her dates try to find in her a victim of the narcos, someone who escaped a land of magical realism and spicy tango. Then, shortly before graduation, she is locked in the youth ward of a psychiatric hospital, a story that is juxtaposed onstage with her auditions to play Evita Perón directed by an Englishman (Julian Sanchez) who doesn´t seem to know shit about Latin America.

Can the migrant integrate into the host society?

Performing as Evita becomes a wild irony. Her story is well known: Eva Duarte was born in rural Argentina, moved to Buenos Aires to be an actress, and along the way she met Juan Domingo Perón and became his wife before he became president. As first lady of the nation, she enjoyed wild popularity until cancer took her life when she was thirty-three years old. Evita became a tragic figure, inspiring all kinds of narratives and iconographies (my favorites are Eva Perón by Copi; Santa Evita by Tomás Eloy Martínez, recently adapted by Star and available on Hulu; and I find Solanas and Getino’s La Hora de los Hornos fascinating, even if I disagree with them so much). Thinking about Evita, you may be envisioning Madonna in the balcony of the Casa Rosada singing “Don´t Cry For Me Argentina.” The musical presents her as a cold-blooded social climber who wanted fame and revenge from the wealthy while a whole nation idolizes her and celebrate her as a saint. The musical dares to equate Perón with Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco, ignoring the numerous differences (and the colonial past) between Argentina, Italy, and Spain. This portrays lower-class Argentinians as ignorant, easy to manipulate and deceive. As a South American spectator, I can´t shake the feeling that a group of artists from the Global North are trying to explain our region to us from far away. Maia portrays Evita Perón on stage, but the director is not happy. She doesn´t sound “authentic.” Her voice and presence are not Latinx enough. It doesn´t matter that she is authentically Argentinian, born in Buenos Aires. She is not fulfilling the expectations placed on her body.

She doesn´t look “sane” enough to leave the psychiatric hospital or Argentinian enough to play Evita. The situation is absurd: how does a “sane” person looks? What does an Argentinian look like? What happens when a non-Argentinian accuses an actual Argentinian of not looking “authentic” enough? Maia resists the authority of the warden (Raffaella Donatich) and tries to establish communication with her. But since she has been categorized as “crazy,” the power imbalance between them allows the warden to turn anything Maia says into a meaningless claim. The immigrant body is not saying or doing what is expected from her, so her voice is drowned. Her English is extremely clear, but she can´t be understood, creating a very specific form of loneliness. Can these circumstances change? Can the migrant integrate into the host society?

Invasive Species is a play about identity and how one constructs a sense of self as a migrant. But it is also about power, about who has the ability to shape who we are and where we can be.

Her only friend and guide in this world is Akila (Alexandra Maurice), a teenager from the psychiatric hospital. In a very tender and moving sequence, they discuss suicide and friendship. It is surprisingly funny in the most endearing way. Maia shares her frustrations, and Akila ridicules her: just do what is expected from you. She is an actress; it should be easy. Smile to the warden. Tell her how good she feels and how much the meds are healing her. Give the director the accent he wants. Be the Argentine they want to see, a body that suffers, who left a doomed place for a better life. Be humble; tell them what they want to hear. This solution feels, at the same time, obvious, funny, and tragic.

Invasive Species is a play about identity and how one constructs a sense of self as a migrant. But it is also about power, about who has the ability to shape who we are and where we can be. Maia seeks a place in a new land, but she is either trapped in a hospital or pushed out of the industry. This operation makes this also a play about space, questioning who can be where, in which capacity, and occupying which positions. Spaces are constantly segmented, pushing and inviting bodies in and out of them. Race and ethnicity give and take “permission” to occupy places and play roles. For foreigners in the United States, just crossing the border and being present in this land is a negotiation. We apply for visas and authorizations while laws carefully establish what we can do. In Invasive Species, Maia´s body is literally locked in the hospital; her movements and behavior are policed and monitored. A real event becomes a metaphor for a body unable to find protection or community. She calls her parents, but they don´t understand. They are in another realm, a different logic, and they shame her for spending too much money. Where is the protection for the migrant body? What are her rights? To enter a space of “freedom,” she must perform. Pretend. Embrace the fact that to be part of that freedom she must give folx in power what they demand.

Maia Novi in Invasive Species by Maia Novi at the the Tank. Directed by Michael Breslin. Lighting design by Yichen Zhou. Sound design and composition by Jessie Char and Maxwell Neely-Cohen. Dramaturgy by Amauta Marston-Firmino. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

Today, I can´t think of theatre as an act capable of transforming the structures of society (two years ago I´d give you a different answer. Maybe tomorrow I´ll change my mind again). But I find in theatre an act of resistance in which, for a short period of time, the rules of the world are subverted. Maia curates a space where her rage and pain can be addressed and power can be ridiculed and called out in ways that are harder to do outside of the theatre. Revolting at the hospital would not get her out. Confronting the director would make her lose her job. But this is not a tragedy. We do not gather to observe the migrant pain from a comfortable chair after paying an expensive ticket.

In June 2022, Amelia Acosta Powell opened the Latinx Theatre Commons Comedy Carnaval by complaining about Latine “trauma porn”:

[it] exploits the suffering of marginalized people to console or entertain the privileged and powerful. So much of the time that Latine stories are programmed, those stories feature narratives about immigration, narcotics trafficking, imprisonment, family separation, or gang violence. At best, this over-emphasis on narratives of Latine oppression is a well-intentioned desire to foster dialogue about relevant issues. At worst, it is a calculated and deeply rooted strategy to propagate harmful stereotypes in order to justify and reinforce the status quo of white supremacy.

Amelia responds to this narrative by claiming that “one of the most powerful and versatile tools that our communities use to tackle oppression is the power of humor.” These statements help me grapple with the project of Invasive Species, a piece that explores new Latine narratives with original strategies, questioning oppression and pain through laughter. This leads me to the question: who is the show for? Is it created for those who have been through similar experiences or for those who do not? I say it centers the first, and in that sense, I find a connection with recent extraordinary shows as Between Two Knees by the 1491s, Exhaustion Arroyo by W. Fran Astorga, or White Girl In Danger by Michael R. Jackson. These plays become sites to reckon and discuss a pain shared by actors, writers, and audiences, centering those who can relate to these stories of violence and exclusion, using laughter as a tool to navigate oppression.

Sam Gonzalez and Raffaella Donatich in Invasive Species by Maia Novi at the the Tank. Directed by Michael Breslin. Lighting design by Yichen Zhou. Sound design and composition by Jessie Char and Maxwell Neely-Cohen. Dramaturgy by Amauta Marston-Firmino. Photo by Julieta Cervantes.

The comedy of Invasive Species is uplifted and strengthened by Michael Breslin´s brilliant directing. The action is set on an empty stage with four extraordinary actors who operate as an ensemble around Maia, constantly changing characters and transforming the space only with the use of their bodies. The action is fast and relentless, taking us from Argentina to California to Connecticut to New York in a blink of an eye. Breslin presents the film industry and the psychiatric hospital as porous, shifting from one to the other, suggesting they are not that different. They are both governed by vertical power dynamics and absurd rules that demand blood.

Invasive Species had a short run at the Tank. As beautiful as it was, it doesn´t feel like enough. It was an opportunity to expand the ideas of what Latinx storytelling is, foregrounding the connections between the Americas and creating space for first generation migrants and Latines who come from south of the Equator. Amauta Firmino, producer and dramaturg of the piece, and Maia herself told me they sought to explore the dark side and the grotesque aspects of the migrant body and the migrant experience, because that is also part of us. Audiences will see spit, drugs, sex, and inappropriate laughter. Invasive Species lets us honor our pain, mock ourselves, and celebrate our pleasure. Maybe, through that, we can find and embrace all of our humanity.

For those still wondering—yes, I hate Evita. But one of my dreams is to wear her dresses in drag and lipsync “Don´t Cry For Me Argentina” at the Casa Rosada. I am also my contradictions, and I want a theatre that can embrace them like Invasive Species does.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here