Melissa Lin Sturges: Each of you has worked extensively with Shakespeare’s plays—as actors, directors, and educators—as well as with community-based theatre. (Here I use Jan Cohen-Cruz’s definition of community-based performance as “a field in which artists, collaborating with people whose lives directly inform the subject matter, express collective meaning”). With so much to pull from, where did you begin?

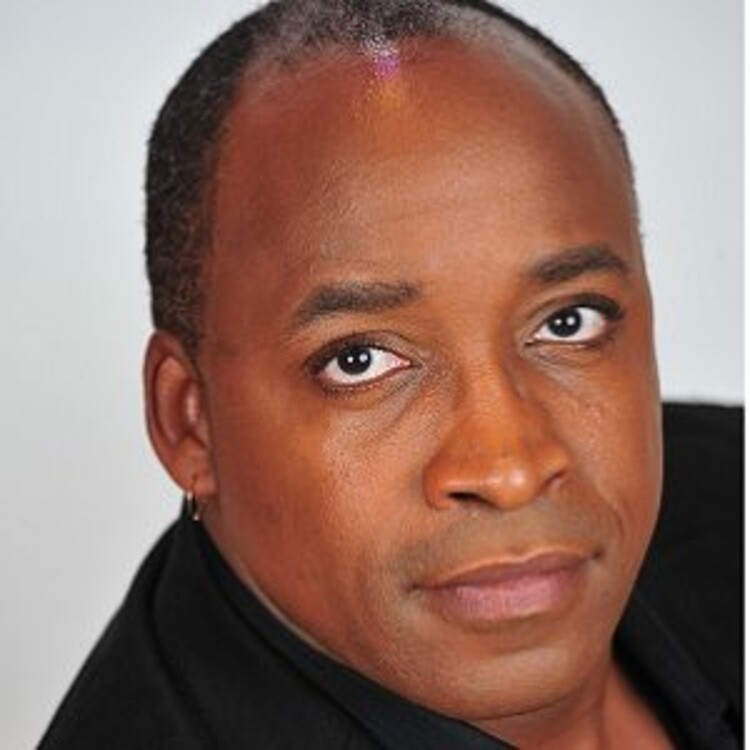

Malik Work: Karen Ann Daniels and I started working together at the Public Theater in New York. Incidentally, we started with some hip hop and Shakespeare workshops for incarcerated participants, which I designed under her leadership and guidance. Because it was during the pandemic, we worked mostly with video projects, which turned out to be very successful. Then she told me she was leaving the Public Theater to join The Folger Theatre (which publishes my favorite Shakespeare editions to teach). When she was situated, she asked me how I would feel about writing a play with her. The play was about memory—about whose stories are told and remembered. So we began to collaborate on Our Verse in Time to Come.

Melissa: Ray, you joined later in this process. Can you speak to how you approached this work as the dramaturg?

John “Ray” Proctor: I was grateful that Malik and Karen Ann invited me in at a time when my primary job as a dramaturg would be to listen. I listened, and I read the script and reflected what I saw back to the playwrights. I would sit with Malik and say, “This is what’s in your story.” I would do the same thing with Karen Ann. I would tell them what the other was saying and what I saw in the play itself. There were so many people telling them what was in their story; I was the interlocutor or the filter for everyone in the room. Malik also asked me what the relationship between prisoners and dementia was. I looked closely at prisons with predominantly Black populations, especially where there were riots. That was some of the initial research I did. But I do think my job was to listen and reflect back, mostly. At least, that was the first part.

When we made it to the actual workshop in March, they brought in Vernice Miller as the director. She was so smart and wonderful. We had Kaja Dunn as an intimacy coordinator. We had the stage manager, Kate Kilbane. We had Nick the 1da Hernandez as the DJ. All of these people were in the room.

We started to see how the circle transforms hierarchy into an equitable place to exist. For us, that became a grounding place for this play to begin.

Melissa: How much of the play emerged during the rehearsal process? Did anything surprise you along the way?

Karen Ann Daniels: How hard it is to stage a play! On some level, a play is only words on a page. It takes other peoples’ embodiment and experiences for a play to become a living, breathing entity.

Working in a partnership can be a challenge, especially when you’re not in the same place, but what I love about this project is the community we built. Things resonated. People felt the emotions we were putting on stage.

In this play we see a positive relationship—a loving relationship—between a Black man and his son. I think fraught relationships between Black characters are something the world expects. We praise Shakespeare for his characters and his stories, but Our Verse in Time to Come feels present and real. This play is about memory. Who has it? Who gets to choose how we remember? This man, SOS, didn’t just sit and rot in prison. He has things he learned and did. And this is valuable; it is part of a larger heritage.

Melissa: Ray mentioned being an interlocutor, a facilitator; and that reminds me of the role of the “cypher,” which is a gathering of people (sometimes around a DJ) for free-style rapping, emceeing, breaking, and beatboxing. The play, which is staged in the round, begins with the question, “what is a cypher?” Can you speak to that initial question asked of the audience and how the play builds from that?

Karen Ann: We start with the cypher as a kind of a circle. Like I saw with my work in correctional facilities, there are so many things in life that are based around the collective and not the individual. The circle is a form of healing. So that’s where it comes from for me.

Malik offered a complete parallel within hip-hop. Hip-hop is also a circle where everyone brings themselves into the space and engages.

Thinking about where we would perform this, we started to see the circles in the geography of Washington, DC. We started to see how the circle transforms hierarchy into an equitable place to exist. For us, that became a grounding place for this play to begin.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here