Two Residents, One Play

Peter Sinn Nachtrieb on writing and Robert O'Hara on directing The Totalitarians at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company

Peter Sinn Nachtrieb's play The Totalitarians was part of a National New Play Network rolling world premiere in 2014, opening at Southern Repertory Theater, then at Woolly Mammoth, then at Z Space. I sat down with Peter and Robert O’Hara, who directed the production at Woolly Mammoth, in the spring of last year to get a snapshot of these two Mellon residents in action just prior to opening night at Woolly.

Ronee Penoi: Both of you had relationships with your theatres before your residencies (and this rolling premiere) began. Robert, we've talked about how that has deepened your residency. Peter, how has the dynamic been for you?

Peter Sinn Nachtrieb: I feel like I'm really interested in how the organization works and feel very invested in the success of the space and company. Especially since it's a time of growth—their budget went up half a million bucks last year.

Robert O’Hara: That's big for them.

Peter: 1.2 to 1.8 is a big increase. So it's interesting to be there at this time where they're eager to grow, but there's the challenge of how to get the money for that. So I do feel invested in the success of it. And I think it's personal, too. I feel like Lisa is one of the few people I trust to produce my work in the Bay Area. Not that there aren't other companies who aren't good too—I've done stuff at ACT and stuff at Marin and sort of at Berkeley Rep (and I would work there of course!). The fact that she exists and that space exists is one of the reasons I can stay in San Francisco. It keeps me artistically satisfied and she's got a level of rigor in the work she does that's not necessarily present at every theatre in the Bay. I do feel, personally, that I want them to grow—and I would also maybe get something from that? But I feel like she deserves it because she's such so artist-centric and artist-forward and that's reflected in the way the residency is structured too.

Robert: It was interesting coming here as a resident after doing three shows already with Woolly because I didn't have to introduce myself to the organization. They sort of knew what they were getting. And though I'm on salary, I still feel like a freelance person inside of an organization, which is good.

Peter: Yeah that's good for me too; I don't feel like I've been bound in that respect. I feel like some writers have had more negotiations about that in their residencies.

Robert: It's a tough thing because residencies are usually for some purpose—you're going to do a residency and come out with something. You've written a play, or you're going to do this production, or you're going to develop this piece—whether it's done or not—but here there's no expectation.

Peter: It's really about supporting the writer.

Robert: Which we're not used to.

Ronee: With Totalitarians in particular, do you feel the fact that you're both residents working on the same show, or is it more of a fun fact that you both have residencies and you're doing the show?

Robert: Did we know when we first talked?

Peter: No, because it hadn't been announced. I didn't know you were part of it.

Robert: We had a conversation. I think I was in Houston at the time. And did I send you Bootycandy?

Peter: Yeah. I read that and I thought...I think this will work. [Laughter]

I'm so happy that I'm not a writer in the process. I can just be the director—Peter has to figure that out. —Robert O’Hara

Ronee: So Peter, what is it like having a director who is also a playwright?

Robert: [To Peter] How is that? I don't think I've given any sort of—

Peter: Dramaturgy stuff?

Robert: Most of my dramaturgy work is at the table or in the direction of the play; not like, “let's just have a dramaturgy meeting.”

Ronee: But does it affect your sensibility, or affect you in an intangible way?

Robert: I guess because I've been doing them both for so long, and I have my own plays that I'm working on, the last thing I want to do is have the playwright side of me come into the room and go, "By the way..." The playwright side is like, "Oh shit, at the end of this rehearsal I have a play I have to write."

Peter: You activate the other part of your brain.

Robert: Sometimes in rehearsal, especially if we're teching something over and over or the actors are running something we've already done, I'll check in on my other self on the computer. Because I think one of the things that's important as a director is to not be so tracked inside of what you're doing that you can't see it fresh. Sometimes I deliberately will put something in front of me so I'll be distracted, or multi-task and come back so it's kind of new in a way. You have to force yourself to be outside of the space while you're in the space, and one of the ways is to not bring the playwright side also.

Ronee: Do you get that question a lot?

Robert: I don't get that question a lot. I get the question about my own work—how it feels to write my own work and direct.

Peter: I think you're very respectful. Its sort of how you approach everyone in the room—you assume they can do their job. So there's no needing to “handle” the writer—whatever that weird dynamic is.

Robert: I assume if you want help you'll ask for it.

Peter: And I have, right? Or if I have a question about something.

Robert: But also if you want to cut something or rewrite something it's like, “Let's do it! Let's try it.” Maybe it's because I'm a playwright. If the playwright wants to try something we should just try it. Some directors want to figure out how it’s going to work before they try it and are afraid of the playwright changing the scheme, you know, in the middle of the rehearsal process or bringing in a new thought. For me, it's just—dump it in, whatever. As I told the actors, I sort of frontload the play with so much shit, that whenever the artistic director or the playwright or dramaturg wants to cut something I say, "Go ahead, I have 10,000 other things." I'm so happy that I'm not a writer in the process. I can just be the director—Peter has to figure that out. Peter, come up with something!

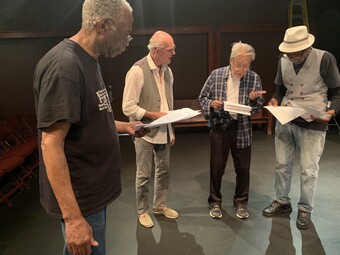

Peter: We had an extra week of rehearsal to workshop, which was pretty great.

Robert: We just sat and read the play because he's had a production, and he's going to have another production.

Ronee: I'm always fascinated by how the rolling world premiere framework affects the middle production. You're not the final; you're not the first.

Robert: Playwrights don't usually stay and be this invested in another production. You do your production and then hopefully you send it out and people do it or whatever. But for you, Peter, to have to actually come and be invested and have us figuring shit out again in a whole other way—

Peter: It's really important, especially because in that first production there were two people involved that had been involved in the play for a couple years. There was a short hand and familiarity with it. Then coming here it was all fresh eyes. That was really helpful and great—having to hear the play again from an outside perspective. That's where a lot of the work sprung from, as well as stuff that I just didn't get a chance to get to. We also had a luxury of time here. I love the second production—you don't have to worry about “does it work or not.” Okay, it's good, and now there's more to be done. Boom.

I don't think for the third production I'm going to be doing a lot of writing. Since it's at my home theatre I'm asking myself, “How can I fill the house, how can I take a lead in helping the marketing of it, and raising the money to do it?” So that's sort of an interesting thing. Now that most of the writing is done, with that production number three I feel like I'm in a unique spot. Plus, I'm on staff there, so I'll want to take advantage of that.

Robert: That's very interesting, because literally you're going backwards. Usually an original play starts at a place that you hopefully have a relationship with and they develop it, and they comfort you, and they help you get the play to other theatres. But here you went from Southern Rep to Woolly and then back home.

Peter: A different opportunity.

Robert: And an interesting idea.

Peter: And different sized productions, too. This is the largest production of the show.

Robert: And Southern Rep is smaller than Z Space?

Peter: Probably, yeah. Watching this thing, I think I should encourage the Z Space folks to look into projection design as solving a lot of problems. This is really affective—knowing all the challenges so I can tell them, "These are the things you're going to have to worry about."

Ronee: So Peter, Z Space is your home turf and Robert, this is your home turf. Robert, has directing here changed, knowing what's going on on staff in a way that you haven't before?

Robert: I think so. I think I've had much more interaction with the artistic staff than I do when I'm normally directing a show, for instance. I'm constantly seeing the artistic director. When you go to regional theatres, you see the artistic director when they give the meet and greet and then you see them at previews when they tell you what's wrong with the shit, because they're usually really busy and they have their own stuff. But here, being here, and seeing Howard in the halls, seeing Howard at my desk, seeing Howard at his desk and working with him on staff meetings—the checking in is a little less abrupt.

Peter: And you have a shorthand and understanding of how he communicates and how to respond.

Robert: And I also feel incredibly comfortable going "I don't agree with that" and moving right along. I'm not trying to impress Howard. I don't need to get another job here. He can't fire me for another year. And I think that Howard also respects that. He says his piece and lets us go do our job. So that's great. And also I think Howard trusts us because Peter has worked here before.

Peter: It's different than the first time—there's more ease working. I think it also comes from six more years of experience as a playwright

Robert: They don't teach you in graduate school how to really be a professional playwright and how negotiate those relationships professionally once you actually get in the room with the people, so sometimes that's tough.

Peter: The Mellon residents are all—none are, I would say, particularly young...

Ronee: And I think it seems to have been designed that way.

Peter: I mean, we're youthful [laughter].

Ronee: Is there anything that you're reflecting on about your relationship that you think would be interesting to the field? [pause] You're also in previews, so it's okay if the answer is no.

Robert: No one would've offered me this play. First of all, I don't know Peter. Second of all, it's a play by a white playwright. And so, my box is not in that playing field in terms of the American theatre. The only reason I got to direct this play is by my own initiative, and my relationship to Woolly. Woolly would not have offered me this play if I had not been a company member and sort of put myself in the position of, "I want to be considered for this play." And I think that's sad. And it is important for our field, because of course, if Peter was an African-American or Latino or Asian playwright, they would have no problem offering it to every white person on earth that directs a play. But it doesn't happen the same way in the other direction. So they're not offering directors of color plays by white playwrights. But they feel no problem with offering plays by people of color to white directors. So I have deliberately been interested in putting myself in places where you don't normally see me, because I don't want to stay in the same place that I've been. I don't mind working with the writers that I do, but nobody wants to see the same stories or the same sort of interactions. I think that is important for our field, and people need to be challenged more to look beyond the seven white directors that you look at whenever you decide to do a production. Not just for me—I have enough that I'm doing. I'm talking about for the other directors of color that are around, and white playwrights have to start demanding more diversity in their directors.

Peter: Ours is strong aesthetic match—it makes a lot of sense.

Robert: The only way you know my aesthetic is because I put myself in front of you in a way. And I think artistic directors need to start putting people in front of people more. Most artistic directors could care less if you have the right aesthetic. They just see a director of note and they will attach them to a play and then the playwright has to work with this individual. I think the question is less about relationships when they're choosing who is directing. At least I see that when I look at the seasons.

It's also tough for me to speak about it because I am a working director and I have a more than enough to direct. Like August Wilson saying, "I don't think that black plays should be going to white theatres," and all his plays go to white theatres. My position is not about me, personally, but about our field. And I think that's important. Just because an African-American director says you should be more diverse does not mean you should hire me.

Peter: Also, you insisted on more diversity in casting. It's interesting, casting Dawn [Ursula] or an African-American in the role of Francine works in so many ways. I've always thought that I never think they're inhabited by any particular ethnic group, but the default is all-white.

Robert: It's also set in Nebraska so, you're like, “What does that look like?” But the character is out of their home.

Peter: It makes her the center of the story. I like that choice. Maybe I don't insist on that enough. I feel less empowered to do so.

Robert: But it does change the dynamic and adds something. People think of limiting it when you start to play with different races. What is that saying? As if that, having that conversation would limit your play to only being about race. It just adds a whole other layer to it. Hopefully it's a very layered play anyway. It's like "how did she get to Nebraska, how did she meet this man?" You start asking those questions. What's exciting about that is, you can build upon that as a playwright in the actual working of the play as opposed to trying to create this interesting marriage. It's already interesting because you're wondering, "What the hell are you two people doing together?" It's working on so many different levels.

At this point in the interview, we realized that we were running out of time to grab dinner before the preview, and refocused our energies! Now, a year later, Robert has just opened the world premiere of his new play at Woolly, Zombie: The American. Stay tuned for more from Robert's residency!

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here