Kunstfest: A Soft Resistance

Weimar’s Kunstfest takes place in the heart of Thuringia and is Germany’s most famous multidisciplinary arts festival. Yet its current artistic director, Rolf C. Hemke, still has to battle to maintain the festival’s diminishing budget—it gets around 900,000 euro from the city and 250,000 in other funding, an amount that has remained the same for almost a decade, though costs have risen. The festival’s importance does not prevent opposition to its existence: some people in Weimar’s local government, usually those who are right-wing, says Hemke, try to get it defunded. Hemke also mentions that right-wing groups redirect funding away from cultural projects to their own. Thus the social cracks appearing from the rise of the AfD can’t be papered over—Berlin might seem a hotbed of art and freedom-loving attitudes, but out in the regions, something more dangerous and oppressive is simmering under the surface. Kunstfest, which took place in person late August and early September this year, tackled issues associated with the far-right—immigration and identity—under its “Thuringia” theme, as well as focused on COVID-19 and the environment. (The AfD, of course, are climate deniers.)

Moving On

It is time, Hemke tells me, for the city to move on from the cultural heritage embedded firmly in the past, including Goethe and Schiller. “Look around Weimar,” he says,” and you will see that it is built on their legacies, yet they were also once considered avant-garde.” Hemke hopes to change this with the introduction of companies like Novoflot (an independent opera company based in Berlin) and Dumbworld (a UK-based company that makes work at the intersection of music, images, and words) to push Weimar’s love of words and music beyond its classical obsessions into unexplored experimental universes. This year, festival projects also focused on the nine-hundred refugees present in the city and included big-name theatremakers such as Theresia Walser and Falk Richter. International contributions came from Malian actor and director Habib Dembélé, Taiwan- and Berlin-based choreographer Shang-Chi Sun, and La Fura dels Baus to name but a few.

What better to reflect on this political turmoil and fallout than with a festival that digresses from the white male point of view and proposes to present Germany as it really is: multicultural, many voiced, and with multiple perspectives on history?

Finding Space, Expression, and Safety in Thuringia

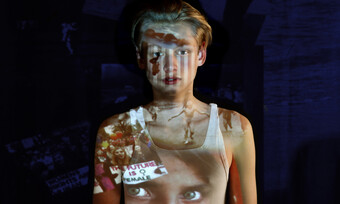

The experimental dance piece Phit-Nan-So (Shelter), created by Sun and visual artist Chaong-Wen Ting, grapples with identity and immigrants making Weimar their home and, more politically, with the idea of transformation of the self within new habitats. Appropriately played out in the corridors of the Bauhaus museum, which has a rich history of international collaboration, this is a fragmented narrative where dancers and musicians slip among the visitors like shadows, not quite interacting with them, not quite ignoring them. Discombobulated steps and hesitant pas de deux are splintered by halting monologues that project a sense of loneliness and disconnection. As time progresses, tables and dolls become instruments of transformation as bodies grow and take root, as if to say, We are here now, in Thuringia.

In the middle of Weimar lies the Sunken Giant—a sculpture of a Black man, created by Walter Sachs, half submerged in Weimar’s clay beds. For Berlin artist Lydia Ziemke’s audio site-specific installation Flucht nach Thüringen–Gestern & Heute (Escape to Thuringia, yesterday and today part II (Surfaced)), which followed from her part I (submerged) that premiered at the festival in 2019, audience members listen through headphones as Iranian refugee Roghaye Wiseh softly assesses her time in Weimar, accepting her dislocating situation, projecting her feelings through the Sunken Giant, and locating herself in the city center, culturally laying claim to its space alongside Goethe. This is a soulful collage of reflections from people from different parts of the globe who have made Weimar their home and is meant to reflect a resurfacing experience the refugees feel as they become more visible in Weimar’s society. Other participants include Iranian filmmakers Salman Vakili and Sahar Darwish Zahdeh, as well as actor Tahera Hashemi.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here