A Call for Equal Support in Theatrical Design

Technical theatre is comprised of designing and constructing. In some areas of design, those roles are separated, and separately compensated. Set and lighting designers overwhelmingly have a technical director and master electrician hired by the company to execute a designer’s plan, even at smaller, non-equity, and storefront theatres. In contrast, costume designers are left to their own devices at all but the largest institutions. Without the support of a technician, costume designers have their hands in each step of bringing the design to the stage—measuring actors, drafting patterns, building costumes, shopping, coordinating rentals, fittings, completing alterations, writing up laundry instructions, coordinating understudy costumes, returns, budgets, the occasional mid-run maintenance, and strike. The stitchers and assistants they work with are usually interviewed and hired by the costume designer and are paid from the designer’s fee, or occasionally the costume budget if there’s room.

Costume design is also the only area of technical theatre in which women make up the majority. …. This inequity stems from our culture’s gendered views on who makes clothing, how much their time is worth, and the often skewed understanding of what skills are required to design and build a costume, let alone an entire show.

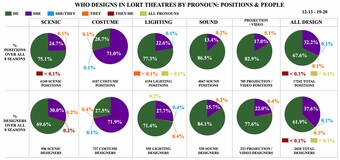

Costume design is also the only area of technical theatre in which women make up the majority. Based on three years of numbers she compiled, Porsche McGovern notes that 76.5 percent of set designers and 80 percent of lighting designers are male, while only 30 percent of costume designers are male in the League of Resident Theatres (LORT). I argue that much of this division of labor (or lack thereof) is based on institutionalized gender bias within theatre and our society. This inequity stems from our culture’s gendered views on who makes clothing, how much their time is worth, and the often skewed understanding of what skills are required to design and build a costume, let alone an entire show. This imbalance compounds inequities between male and female designers. It relegates costume designers, mostly women, to artisans, while set and lighting designers, mostly men, remain purely artists. This enables set and lighting designers to focus purely on their design, while costume designers must be both designer and technician. It means that a costume designer cannot design as many shows per year as a set or lighting designer can, and therefore earns less. It also affects the kinds of theatre we make and the types of voices theatre gives voice to. And, finally, it harms the collaborative dynamic within a production team and influences theatre designer diversity.

On the surface, the allocation of support and resources within a theatre company is based on the design discipline. Female set designers are offered the same resources as male set designers within an institution, as are male and female costume designers. But this is where our culture’s gendered views on garment work come into play. For most of Western history, paid garment work was seen as men’s work. While women made garments in the home, men held the vast majority of paid positions as tailors and patternmakers up until industrialization in the nineteenth century. When the modern garment factory was born at the end of the nineteenth century, women were brought in as stitchers, a source of cheap and dependent labor.

More than a hundred years later, the labor of garment work is still effectively women’s work and is incorrectly considered, much like modern agricultural labor, to be unskilled, disposable, and worth minimal compensation. In the age of a globalized garment industry and the five-dollar Old Navy T-shirt, garment work is performed by women with few rights and resources, women who are not deemed worthy of a living wage and have little voice with which to lobby their case. Anyone who has ever completed a garment, let alone patterned one, knows that garment construction is, in fact, highly skilled labor. Yet I see a direct correlation between how much any stitcher’s skills are valued and the market rate for mass-produced clothing.

Given our gendered views on who makes clothing and how much their time is worth, it is telling that in the female-dominated, garment-based field of costume design, designers are expected to act not only as designer, but also (still) as laborer. We should move beyond these outmoded expectations. If and when designers choose to construct their designs, the time and labor that go into each process should be compensated fairly, just like any other area of theatrical design. Between design disciplines, as between genders, support should be equal and resources should be commensurate.

As companies, theatres have done little to question how often set and lighting designers only work with hired technicians. It serves their bottom line not to. Statistics show that women are more likely to take on uncompensated work than men. For better or worse, it’s a tactic used by ambitious women who need to maneuver in our culture’s (and, dare I say, theatre’s) male-dominated system. Women are also much less likely to ask for increased compensation or assistance. In many ways it’s a rigged system in which women who don’t take on extra work are penalized for seeming uncooperative, while women who ask for increased compensation are often deemed entitled. Theatre companies benefit greatly from this free labor.

Artistic directors, production managers, and designers alike have also done little to reassess the expectation that some, but not all, designers are both designer and technician. We have grown accustomed to the roles we all play. The familiarity makes them seem natural, ubiquity makes them seem fair. Yet if a set designer were expected to design and build a set at a midsize theatre they would likely balk. Conversely, when a costume designer says that they don’t build their designs, it’s viewed as overly demanding or as a sign of incompetency.

As a costume designer, I am also guilty of maintaining the role of costume designer–technician. By being willing and able to do some work that I am not paid for, I am maintaining a norm that limits costume designers to people who are privileged enough to take on extra work without compensation. When I build the costumes I design, I make it harder for costume designers to request assistance and gain an equal footing. The thousands of unreimbursed miles I have driven for shows every year are another barrier I have helped build. When I complete alterations or return mid-run to repair a shoe, I am limiting who can afford to work as a costume designer. I have often seen this donated time as the crux of making art that I deeply care about and that has my name attached to it. (Not to mention the price I have to pay to “make it.”)

Designers of all disciplines will be more diverse if we support them equally. And theatre will be better for it.

Like any art form, the process of making theatre can’t be separated from the final product. As creators of art, we benefit from collaborating with people with diverse viewpoints and backgrounds. We create better and more fulfilling work when our concepts are challenged and new ideas are brought into the room. Theatre is a response to the times, a place where people can gather and “hold up the mirror.” In order to make our art relevant and more reflective of our diverse society, we need to promote diversity backstage as well as on stage. Designers of all disciplines will be more diverse if we support them equally. And theatre will be better for it.

As collaborative artists who come together to solve problems in the most creative and technical ways, I am confident that we can balance this load. My goal is for theatres that hire technical directors, carpenters, and master electricians to hire technicians for their other designers. The smallest of our theatres, which rely on volunteers to build their sets or cable their lights, should coordinate the same resources for other designers. Changes like this happen over time, so I would like to start the conversation and begin moving forward now.

From my perspective as a costume designer, there are some small, easy steps that could be implemented relatively quickly at any theatre, including small storefronts. All theatres should reimburse production-errand mileage and add a budget line for costume builds or alterations. If a storefront can hire a technical director, they can afford to budget for these items as well.

If they have not done so already, midsize to larger theatres should also add an assistant and maintenance/costume-build position for each production that suits the size, scale, and style of the production. This is a larger budget item within a season and may take longer to fully implement, but goals should be set and planned now as budgets and grants are being prepared for upcoming seasons.

I also encourage companies to look at how they can support their props, video, and sound designers, among others, and create a long-term plan so that all designers have commensurate resources, equal support, and therefore comparable worth.

We are all affected when resources are divided unequally. The current imbalance restrains creativity and collaboration, and limits the impact of our art. It’s a dynamic that favors privilege and therefore restricts designer diversity. And, as it is rooted in societal gender bias, it compounds gender inequities. We need to work consciously to correct that bias. The current system is a product of its history. We must move beyond our history and actively work to equally support all designers.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

The most valuable advice I ever received in my college education was : You agreed to do the job.

- There is much wrong factually with this writer’s claims. Costume and Set Designers are paid the same amount of money for their designs on all LORT contracts. Lighting and sound designers are paid considerably less for theirs. Costume and set designers put in approximately equal amounts of time designing and realizing their designs. The implication that costume designers are working their fingers to the bone, while other designers are sitting back and relaxing, is just ignorance. At the lower LORT levels, costume designers are asked to play 2 roles, but scenic designers are asked to play 4 or 5, being responsible for designing, building, painting, propping, and often lighting the production. On top of that, the design process itself is often far more time consuming for set designers, with full renderings, draftings, and models needing to be completed before any of the other work can start. Beyond that, there is a difference in expectations for set and costume design. Many costume designs are executed on the fly, perhaps after a day or two of research and pulling images from magazines. The design process is looser, with there often being an understanding that adjustments will be made on the fly, as new discoveries are made. Try doing the same thing as a set or lighting designer.

- Costumes are rarely built from scratch for the majority of LORT productions. It’s more about buying/renting/scavenging and adjusting. There are also a lot more opportunities for shortcuts than this writer implies. If you can get 90% of what you were after and get some sleep at night, that’s the decision you should be making. Ultimately, you are being paid to be a manager just as much as you are to be a designer. If you let your employers know that they are only going to get 90% of what they expect, but you deliver the product on time and on budget, you will be hired far more often than someone who aims for unachievable artistic brilliance or who tries to make the theatre happy by giving them everything they ask for, but who turn the process into a miserable mess.

- There are no idle moments in set or lighting designer’s days when working on ANY budget level of theatre or the performing arts. On lower budget productions, every designer in every design field is expected to scavenge and work with what they have. On higher budget productions, the resources are apportioned as needed. Regardless of the budget level, on modern dress productions, set design may get a bigger piece of the pie, and on period productions where costumes are being built from scratch, far more money may be dedicated to the costume department than any other design field. Moreover, a conscious decision might be made to rely on costume design near exclusively to fulfill the visual narrative, so that more money can be budgeted in that direction.

- Nearly all LORT Theatres either maintain costume technicians, or provide access to volunteer labor. Only the smallest of LORT theaters are guilty of leaving the designers completely on their own, and anyone who tries to make a living designing at those theaters exclusively is a damned fool. Consider it a labor of love, and find another way to use your talents to pay your bills. Starting out as a designer, I had many all-nighters as someone who served as both lighting and set designer on most productions I was involved with, and those experiences taught me to find a better way to manage my personal resources, and to learn to say “no.”

- Article XXV of the LORT Agreement allows for hiring of assistant designers, paid for by the theatre. Assistant designers are hired for costume designers on LORT production far more often than for set designers, particularly in theaters that lack full technical staff, despite the fact that set designers usually spend far more time preparing paperwork for the execution of their designs, than costume designers do for theirs. In other words, the additional labor is built into the system.

- You need to know how to budget well, and you need to ask for additional resources up front, so the theatre can make sure they aren’t asking any department to do things they are incapable of achieving. When the numbers don’t add up, the difference is going to come out of your hide. You need to make a decision whether or not you are willing to donate a piece of your life to a theatre in exchange for the design opportunity. If you don’t do these things as a professional designer, the problem isn’t the system, the problem is you.

- There are other forms of wardrobe design, for film, TV, commercials, etc, that pay far better than theatre, and require much better resource management and communication skills. Very few professional scenic and lighting designers try to make their income through theatre alone. The average for the most well known designers, who maintain a stable of assistant designers and support staff, might be 10% theater, and 90% work for corporate clients who have deeper pockets. That’s just a reality of making the finances work. Theatrical costume designers by comparison, tend to do much less of that corporate work, and thereby limit their earning potential.

I don’t see this as a problem with the system itself, I see it as a problem with the false expectations of some costume designers. The most successful costume and wardrobe designers are those who learn to budget their time and resources well, who know which shortcuts to make without sacrificing the design ideas, and who know how to firmly say “no” when needed.

I'm completely stunned. I have never witnessed such deeply ignorant man-splaining in my life. And I'm a man.

I was going to offer retorts to all of your points, but suffice to say that as a man working in the theatrical costume design discipline I'm VERY confident saying you are utterly, naively wrong on so many multiple levels it's stupefying. I can unequivocally say I wear more hats that my fellow designers and am responsible for executing more responsibilities than they are AND THEY KNOW IT. We have discussions about it and they acknowledge it and are trying to take steps to help.

It boils down to simple evidence: I can't sit in the same room with the rest of the designers post-rehearsal to get notes because I'm too busy helping novice wardrobe folks learn how to do their job--which is a hat that a wardrobe supervisor should wear but I have to because there is none.

In my local area, I build/do alterations/shop/create crafts/do paperwork all by myself for all my projects while my fellow scene designers get to have the possibility of an overhire scenic charge painter in the beginning of the process as a matter of course. It's a special circumstance for me to get a stitcher, and requires much huffing and puffing as budgets get rearranged even if they don't flat out say I have to pay for my own help.

I know *FOR A FACT* that the amount of attention and manual dexterity it takes to do 24" of hand sewing is more mentally taxing than it takes to distress wood with a paintbrush on a floor. I may not be working with saws and hammers but I am no less exhausted after putting in a 17 hour day doing alterations than a scenic tech sanding a floor. I know this because I've done it. Explain to me why I have to make the "handful of designs" AND sew them when someone else gets a TD to do it for them *as normal expectation of partitioned responsibilities*? Why do I have to fight for my own personnel?

Your capacity to victim-blame is devastatingly apparent, and you undermine your own arguments. Your statements reek of inexperience and woeful ignorance. Your bias is rampantly on display. I suggest you pay much much more attention to what your collaborators are actually doing for their processes, or you won't have many folks left who are willing to collaborate with you.

Have I man-splained it enough for you?

Thank you Corey, you've greatly lessened my urge to tear my hair out. And JGSID, some of us do actually make costumes from scratch or even more often are expected to make new exciting stuff out of old crap (one of my specialties):)

Preach, Corey! Thank you for man-splaining to JGISD.

I think this is excellent and will just add that it is reflected many fold in faculty positions. Set Design faculty always have TDs who run their shops and oversee the construction while Costume Design faculty are expected to design the show AND run the shop. Two jobs to the one of the scenic design positions.

Surely you jest. How many renderings do those costume staff do, as set designers spend weeks or months creating hundreds of pages of highly detailed renderings, draftings, treatment schedules, models, etc? In addition, the designer in those positions is also responsible for shopping for or detailing specific finish products, propping or painting the show, and often lighting it as well. The work is far more balanced than you are letting on.

Apologies for typos below. In a rush.

Thank you for writing this! I design both scenery and costumes in Los Angeles, which means, I work a lot in small theatres as well as large ones. I get much more support on scenery. Because of the intense amount of labor involved in costumes and the lack of help provided- rareley an assistant, and I have to fight for alterations help, or swallow the cost of extra labor myself, I have almost completely given up on 99 seat theatre costume design, which is sad because some of those shows are the most creative. But the work load is physically crushing. I could elaborate, and will, but I have to run as I am in tech week! I really appreciate the opportunity to address this. USA has looked into the problem. Costume designers end up making much less PER HOUR than other disciplines because of the intensely detailed labor involved. Not to mention the schlepping!

I think you are comparing apples and oranges here. A lighting designer is working from a finite set of instruments to create and design the look and feel of the production through light. He or she does not have to build those instruments, construct the bulbs, or create a board to control them.

Most of their design work is done on the computer in CADD systems these days by themselves. When it comes to actually hanging the lights, then the ATD or TD along with the hang crew will come in, along with the designer, and hang the lights. Next of course is the focus, which again requires the designer to be on set for. Then the constant changes that may happen all the way up until opening night.

The type of work it is requires that the lighting designer have a team or else it would never get done. One person cannot climb an a-frame, hang a light, guessa focus, walk out to the house, take a look, climb back up, refocus, check again, gel, back to the house again.... you get the idea. With the costume designer you need to step back a few feet and you can see your work.

Also, very different from the lighting designer, the costume designer has almost an infinite amount of possibilities when it comes to fabrics, design choices, accessories, etc. In order to really get their concept built, they NEED to be there from every phase, in the shop building those costumes.

I have been involved in the theatre all my life and I love every role on and off stage. But bottom line, unless you have a broadway hit, there is not much money flowing through most theatres and you work with what you can. it is a labor of love. This is why I stopped attempting to "make a living" in the theatre years ago and instead just volunteer when I have the free time to do so.

I think you are missing the point. It is not that the costume designer shouldn't be involved in all the decision making processes involved in creating the costumes, but that the costume designer is often expected to provide a significant amount of the labor involved in building the costumes without being properly compensated or offered the same level of support.

The lighting designer does not have to construct the instruments, but does he/she have to make sure they are all in working order or schedule maintenance or repair and/or arrange rentals when they are not? Usually, those tasks fall to the technical director.

In costumes, the designer who is left with no assistant and no shop manager has to maintain equipment, schlep it to the repair shop when needed, shop for basic supplies (thread, elastic, snaps, velcro, etc.), often requiring making trips to stores to obtain those items, costing travel expense and time. Costume designers usually "donate" a significant amount of unpaid time to a production, particularly if they are paid the same fee as the set and lighting designer, but also have the full responsibility of the build without additional funded labor.

Any argument that says costume designers work their fingers to the bones while set designers coast through productions while taking naps and enjoying cocktails, is ignorance, and is deeply disrespectful to the rest of the design team. Costume designers have to create a few renderings before the technical side of the process can begin. Set designers have to spend weeks and sometimes months creating detailed technical drawings that explain every piece of wood, detail finishes, paint treatments, etc. Multiple renderings demonstrating mood is required, as are fully finished models.

When it comes to executing designs in productions with lower budgets, costume designers have to wear 2 hats. Set designers have to wear 4 or 5: Design, construction, paint, props, and often, lighting, all for the same small fee. In LORT theatre, costume and set designers are paid identically, although costume designers have bigger staffs available to them, and design assistants are approved (on the theatre's payroll) far more frequently.

If you are having difficulty matching the resources to the job, it's probably because you're a poor communicator and manager. Learn to define the limits of the capabilities of the budget and resources early on with each project, and make management aware of their limitations of what can be achieved with the limited resources they have to work with. Learn to say "no" when it's necessary. Theatres are far happier with designers who fight for clean simple designs while bringing the project in on time and on budget, than they are with someone who produces brilliant "art", but who makes the process unbearable.

Design is more about management than it is about art. A lot of theatrical costume designers haven't learned that lesson.

Most importantly, recognize that you agreed to do the job. Nobody twisted your arm. If you can't handle the heat, then talk someone into installing an air conditioner, or get out of the kitchen.

You're missing the point. What she's saying is the the costume designer is being required to do the "costume equivalent" of climbing the A-frame, hanging the light, guessing the focus, walking into the house to check, climbing the A-frame, refocusing............. In the small low/no budget venues ALL of the work falls to the costume "designer" So if there were parity, then yeah, the lighting desinger would be doing what you blythly dismiss as not possible.

I, too, feel it's an oversight to not include the sound designer in this, but perhaps you didn't discuss sound is that it doesn't fit into your theory. We certainly understand the struggle of the costume designer because as sound designers we always are our own shop in content creation, even in the highest commercial levels of budgeted theatre.

What doesn't fit into your theory is that sound design is a male-dominated field. So from my perspective it's not a gender bias, it's a 'what can we get away with' as far as labor is concerned. For example, licensing music is always a discussion because some theatres expect found music to be free usage. Then as a composer to ask for additional compensation seems like something they can't afford. I've placed riders in my contracts to try and teach the field what the standard is for my field.

In the end, it feels like those that get away with not compensating labor, will continue to balance their budgets accordingly.

I think you are taking this personally and not looking at the real comparison of the quantity of work in the areas she was comparing.

Hi Leslie, as what she is comparing and discussing closely resembles what sound designers go through, I do feel that she missed an opportunity. It's not personal. I feel, as a woman pioneer in my field, invoking gender as your theory when we sound designers experience the same in a male dominated field is something that anyone researching a paper would welcome. The more information the better in order to come to a concise conclusion. I don't devalue her experience, I offer a different perspective.

I agree and support more technician suppport for costume designers. I do have one clarification. You say that most set and lighting (and sound and projection) designers are male. What is more accurate is that most set, lighting, sound, and projection design positions are filled with male designers. There are plenty of female designers in those metiers who have a hard time getting hired and would love those jobs that are overwhelmingly given to male designers in our freelance-based industry.

Yes, the numbers I referenced only count hired positions. And I completely agree. Gender bias is alive and well when it comes to hiring...

Thank you for a thoughtful article. I can see by the feedback that there is room for improvement in several crafts. We need to acknowledge that and support each other wherever we can.

As for costume technicians, in Seattle where we have more than dozen LORT theaters, the costume technicians realized that they too were allowing the $$ disparity to prevail and needed to speak up for themselves. For us that meant going Union, like the technicians in the other crafts (at the same venues). It took more than a decade of organizing and working on contracts, but we now have parity wages in our venues across the crafts. It involved educating the venue (many of whom were run by women) to the point where they became partners in the effort. It creates a wonderfully unified work-place when people working side-by-side are paid the same rates, under the same conditions.

We (IATSE Local 887) hope that it does have the effect of creating a standard that is met in the non-union represented small theaters in the area, for both designers and technicians. We live in a progressive city and work with non-profits, so it is not as hard as it might be elsewhere. Keep talking and keep pushing forward. It is worth it.

Unfortunately the effects have not in any way trickled down to smaller venues. I've been costuming in Seattle since 2011 and have never once been allocated the resources an assistant or wardrobe person. I'm currently in tech for a show which called for 23 head to toe looks including 5 wigs on a $400 materials budget. I have no assistant, no stitchers, no wig designer. It's literally just me, working in a corner of the dressing room, and relying on the goodwill of other fringe theaters to lend to me from their stock with no fee or in exchange for comps. This is one of the more amply resourced shows I've done.

I would encourage you to look beyond just designers especially when talking about costumes, because most if not all of the LORT resident theaters have some form of costume shop/costume shop crew.

I think it's dangerous to lump costume technicians in with costume designers. Yes, there's a fair amount of overlap, as most designers can make it through at least basic construction/alterations, but there are frequently highly specialized costume technicians in LORT shops that are getting lost in the shuffle when designers start pushing for more.

As a draper/cutter/tailor, I'm in charge of leading a team of people (even if it's a team of me and one other) in making sure that a designer's vision gets realized. I work a normal workday (8-5) often plus evening hours, depending on what kind of demand there is on the shop. I frequently make significantly less money than a designer and have significantly less freedom to take on additional or outside jobs to make money. I also generally make less than the scene shop technicians, because their environment is "hazardous" (aka "manly")

Don't get me wrong, I'm all for everyone pushing for better treatment across the board, as a rising tide lifts all boats, but I think that you're running a big risk when focusing exclusively on "designers" of yet again leaving the costume techs in a metaphoric basement somewhere, slaving away in the thread mills with little to no chance of being lifted up as well.

Agee 1,000 times!

Yes. Costume designers and costume technicians are very different roles which should not be lumped together, but often are in all but our largest (mainly LORT) theaters. I know that similar issues to what I wrote about affect costume technicians, and while I was focusing on the labor issues that I have seen faced by the majority of (American) costume designers, I am eager to hear similar conversations focused on costume technicians.

Ironic that you left Sound completely out of your discussion.

As a costume designer I wanted to speak from my own experience, and discuss the historical, economical, and gender based issues that come into play in that field specifically.

I did mention in the article that a few other areas of design should also be addressed: "I also encourage companies to look at how they can support their props, video, and sound designers, among others, and create a long-term plan so that all designers have commensurate resources, equal support, and therefore comparable worth."

I appreciate the line about video but right at the start of the article you do make it sound like costumes is the only one with limited or no support. And the scale of theater really has to be taken into account, at the lower end the lighting and set designers are also doing all their own work, and in the bigger theaters costumes has an entire shop and wardrobe crew while video still has little to no support. It seems like the article is addressing a very specific level of theater.

Yes, sound and video are important and need discussion. But the it seems to me you are trying to derail the conversation and her very valid points.

Wow. Thank you is not enough.

Thank you!

Hey, I like your piece, but I'm a little bit confused about your point that costume design is the only technical field that is has a majority of workers who are female identified. Specifically the quote" Costume design is also the only area of technical theatre in which women make up the majority." The data set that your hypothesis comes from only includes designers, and not backstage builders, props people, or stagehands. Is there data from this group? I'm not sure that "designer" and "technician" are interchangeable terms all the time.

There is certainly a large debate amongst props people as to wether we are designers or technicians.

Also, can we infer from the top that things are the same at the bottom? Does this data hold true for non LORT companies?

Thank you for your thoughts. I know a few people in Chicago are working on collecting Chicago-based data on diversity in theatre (mainly designers, directors, and playwrights), and I am also very interested in how non-equity theaters numbers differ from the LORT data.

I was only looking at design for this piece, so yes, I was not making a blanket statement as to the gender breakdown of technicians. It would be wonderful to look into that as well.