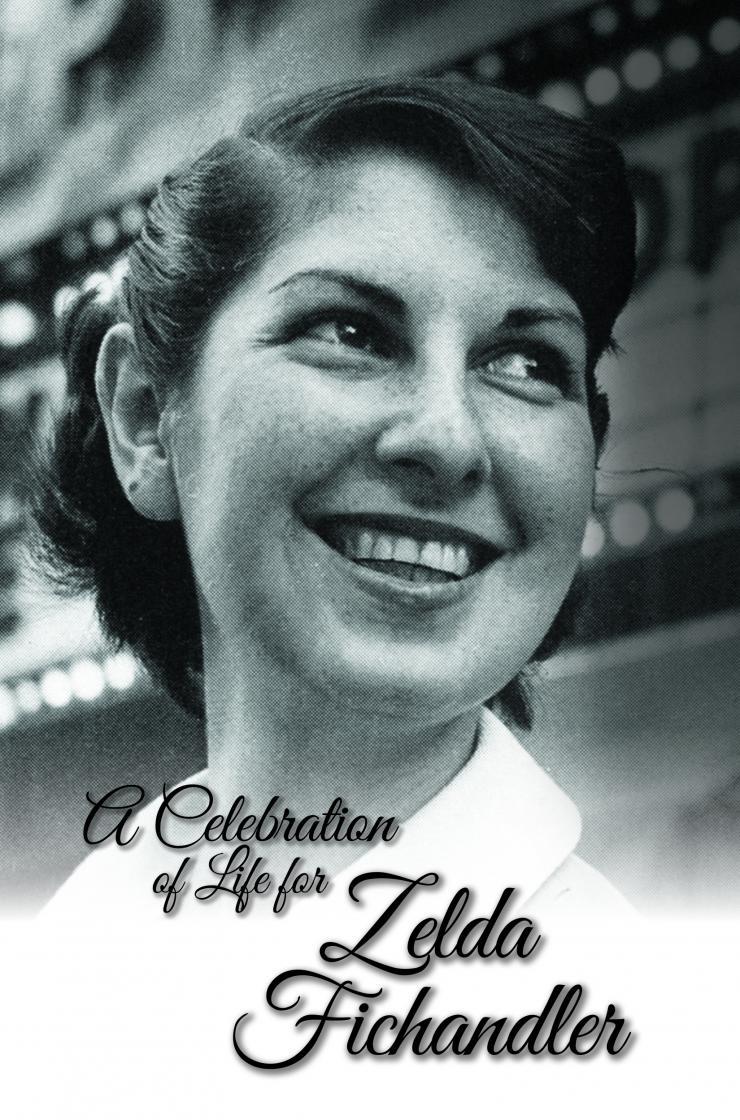

A Celebration of Life for Zelda Fichandler, Arena Stage, October 24, 2016

Remarks by Laura Penn

“…To be tough in the service of something that is tender.” Tongue-tied and terrified as a naïve box-office staffer, and still later when I was with Living Stage, I would pass Zelda in the maze of concrete hallways that linked the Arena to the Kreeger to the Old Vat and back again, hoping to catch her eye while praying she wouldn’t notice me in all my awkwardness.

I was in awe of her intellect, reading and rereading her words, and desperately trying to keep up in staff meetings, retreats, and first rehearsals, not wanting to miss the next phrase that would be the one to unlock a whole world. I was graced by her friendship, particularly in this past decade. When we weren’t sharing stories of sons and grandchildren, or talking politics, history, and world events, she was inspiring, compelling me—and, I guess, demanding that I not waste a moment of my time. I must harness and direct my ambition in service of the soul of the theatre. I must be tough in the service of something that is tender.

In 2008 I arrived at the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society on the eve of the Union’s 50th Anniversary. Founded by a tight group of Broadway stars, SDC had grown to become a national force in support of directors working across the country. We challenged ourselves to find a way to mark the moment, to demonstrate to our Membership and the field the arc of the past 50 years and our commitment to the future.

It was decided that the SDC Foundation, the not-for-profit foundation of SDC, would establish an award to recognize an outstanding director or choreographer making a unique and exceptional contribution to the theatre through work in the regional arena. And it would be named for Zelda.

Zelda was a leader among leaders. She loved directors—directors with expansive vision, with unrelenting passion, who pursued their craft with tenacity, always setting the bar higher and higher. Directors with drive and determination to bring something into being. Zelda was deeply committed to inspiring those who followed in the footsteps of the Founders, and with all her heart wanted to shore them up as they faced the daily challenges of their chosen ministry—requiring that they demand the best of themselves and those around them, as she and her peers had.

Over many months, working closely with Zelda, we developed the criteria.

The Award would not be for lifetime achievement; it would honor an artist for both accomplishment to date and promise for the future. We would witness an artist in the center of their artistic life, working with the same passion and dedication as the founders of the regional theatre movement—founders such as Margo Jones, Bill Ball, Tyrone Guthrie…Gordon Davidson.

The Award would recognize remarkable artists dedicating themselves to a community over a long period of time, and through that commitment transforming their region’s theatrical landscape.

The Award would be for work that is hard, for work that is necessary, and it would encourage these artists and others who follow to carry on and ensure that dynamic, extraordinary directors can thrive while creating great theatre all across the country.

In honor of Zelda it would be for courage and bravery. And—her word, not mine—it would not be for sissies.

Since its establishment in 2009, there have been eight winners, twenty-one finalists, and many hundreds of nominations. Some knew her well and are here with us today. Others are artists who otherwise may not have had an opportunity to sit with her, to speak with her. And in the years ahead there will be many more who, through this Award, will take with them a bit of her spirit and the responsibility to carry on.

She changed our hearts and minds, and the world. She altered our DNA. To meet her was a visceral experience, she was a force—you were changed. I know she is here, in our cells, in the walls.—Laura Penn

I like to think it brought her joy to get know these artists, and that she appreciated knowing SDC would join with many in this room to carefully steward her legacy.

She changed our hearts and minds, and the world. She altered our DNA. To meet her was a visceral experience, she was a force—you were changed. I know she is here, in our cells, in the walls.

In 2009, Zelda wrote a speech that was to be delivered by Jane Alexander at our Gala announcing the Award. The speech was too long—way too long—and it arrived at the eleventh hour (shocking, I know). I was struggling to get into my gown, and Tom Moore (an SDC Board Member and the champion of the Award) was on one side with a red pen, Jane and Ed Sherin on the other, and Zelda on speed dial.

When I looked back through my Zelda files a few weeks ago to try to prepare for this moment, I found a fax with a few suggested cuts—only if we had to! But we had to. In these nuggets of pure gold, one paragraph stood out. It felt almost like she left it there for me to find—to share with you today.

We are each an original. We come into the world at the cost of alternate ovulations, alternate lives really. The chances of our being parents’ son or daughter is in the vicinity of one in ten million. The fundamental identity that we are born with may or may not at all suit the identities of our mother or father; we may even be born into the wrong house or even into the wrong destiny. But if we have the talent to create a beautiful thing that wouldn’t be there but for us, we are blessed. And in addition to repairing the world, we have the opportunity to repair ourselves, make ourselves whole, a project that can engage us for a lifetime and for which, I believe, we have landed on earth.

Thank you.

***

Remarks by Teresa Eyring

Over the years, my path intersected with Zelda’s on many occasions. And some of my favorite encounters were visits with her at her apartment after I started as executive director of TCG. She would reminisce about TCG’s founding in 1961, how she was one of a few folks who were invited to the Ford Foundation to discuss the idea. What a big deal it was. And the red dress she wore to mark the occasion.

I got my start in theatre here in Washington, DC, in the early 80s at the Woolly Mammoth, which had recently formed as a new kind of theatre that would shake up the nation. Perhaps the very fact that there was a perceived need for a such a “shaking up” meant the resident theatre movement had done its job. It had arrived, and established itself enough over three decades to inspire a next generation of theatre makers who would set out to challenge it, to try something new, to start another revolution—just as Zelda and her colleagues had done when they founded Arena Stage and fueled a resident theatre movement.

What Zelda set in motion was not a static gift for the benefit of a single community or era. She carved out a model that others of her own and future generations could replicate or at least approximate, and a generous ecosystem that others could participate in and draw strength from. Through her constant assessment, critique, and unending passion for the work, she gave everyone in this field an artistic and intellectual compass that reminded us why our theatres exist, along with a reality check that there may never be a time when the challenges endemic to this work will finally be overcome.

In the “long revolution,” Zelda said:

We wanted to create a form for theatre that would enable us to insert meaning and beauty into our culture so that people could reach out and touch it simply and directly. Despite hazards and harassments, we have in our various ways done just that. It was a miracle of sorts. For not only did we have to construct the methods to carry out our idea, but we had to train an audience to know that they wanted to have what we wanted to give them. And that was not an easy struggle.

And of course it still goes on.

Zelda wasn’t kidding about the miracle of the movement. She often paraphrased a quote from her hero and movement co-founder Margo Jones who said in the 1940s. “Imagine if there were forty theatres across the country, what a rich land we would be—how the experience of life that all those theatres could afford, would enrich the lives of its citizens.”

Zelda, along with Margo, and Nina Vance of the Alley Theatre are the founding mothers, all starting resident theatres within a few years of each other from the 40s to the 60s. As well as other founders, some of whom are here today.

Now in 2016, we stand in a national theatrical landscape that includes not just forty, but thousands of nonprofit resident theatres, hundreds of thousands of theatre makers, millions of audience members, and billions of dollars of economic impact. By the way, I don’t think economic impact was one of the driving forces in Zelda’s mind when she was envisioning the founding of theatres outside of New York, but I thought it was worth noting. Because we live in a world where the contributions of our theatres and artists are vast, and the challenges of staying afloat are sometimes vaster. And if there is any unfinished business, one of the pieces is how to accomplish greater economic resources for the field, combined with greater equity within the field. And I am proud that we are working on that together and indeed, following Zelda’s lead in many ways as she believed in this.

Among the hazards in the early days was getting audiences to care about both classics and new work, creating a whole new funding model—including making 501(c)(3) status available to theatre. Eventually, it was dealing with the culture wars, alongside the challenges of increasing competition from technology and new media. All of these making it more difficult to generate and maintain that simplicity Zelda talked about—the moments when artist and audience come together in real time and space, for the experience of something beautiful on stage. And yet, none of this stopped her.

Those of us who are part of the national theatre community and audience today are the beneficiaries of what Zelda created, from the very first minute she had the notion that it was important to “create a form for theatre that would enable us to insert meaning and beauty into our culture,” to her resilience and ability to question assumptions, articulate purpose, restructure broken systems, and reinvent. Her vision brought about the widespread employment of theatre artists nationwide, a wider platform for new work, a bridge between commercial and nonprofit worlds, support for a diverse pool of designers and technicians. And especially, she brought something of beauty to the community, whether or not that community knew they wanted it.

While we stand on the shoulders of a giant, and reap the benefits of her creation, we are in no position to rest on those laurels or coast on the successes. Rather, in Zelda’s honor, we and future generations must look at what the world is asking of theatre makers today. We must build on what exists while carving out new theatrical life that responds to the artistic, economic, and political present we inhabit. And recognize that our journey is about making the world better—not just for us but because of us.

In so doing, we may have to construct new methods and train new audiences and communities to want what we have to give. Along the way, we may navigate new hazards and harrassments…

But, taking constant inspiration from Zelda’s memory—from what she accomplished and what she gave us, we will go on.

And we will make her spirit proud.

***

Photo courtesy of Tazewell Thompson.

Remarks by Tazewell Thompson

I think continually of those who were truly great.

Who, from the womb, remembered the soul’s history

Through corridors of light, where the hours are suns,

Endless and singing. Whose lovely ambition

Was what their lips, still touched with fire,

Should tell of the Spirit, clothed from head to foot in song.

And who’s hoarded from the Spring branches

The desires falling across their bodies like blossoms.

—From “The Truly Great” by Stephen Spender

It is very clear: I am a lucky so-and-so. I was born under a most propitious star. The planets all brilliantly aligned. Jupiter was ablaze somewhere in the mid-heavens, rising in my tenth house of great expectations, as a comet’s tail passed over conjunct or trined or sextiled with mercury, making me a student for life, interminably conscious of receiving and filtering good news and glad tidings—birthed in double Gemini, with a new moon in Capricorn. This cosmic Milky Way formation would lead me on a life path journey that would connect me, in the still formative period of my life, to she who would shape mist into substance: Zelda Fichandler.

Zelda was a dear friend, mentor, and because I lacked a mother in my life, I latched on to her, and she allowed that attachment. She brought me to Arena Stage in 1987; it changed my life. We wrote letters, cards, notes to each other—even though sometimes in the same building, on the same floor—for almost thirty years. We spoke by phone, endlessly or in short spurts on a wild variety of topics, several times a month. And in the last years, two to three times a week. She provided me with a reading list of plays and authors that I must “want to know.” She entertained me with memorized lyrics of standards from the 1930s and 40s. And I return a lyric to you now Zel: “The way you haunt my dreams, the way you changed my life. No, no, they can’t take that away from me.”

She read drafts of my plays, giving me incisive, perceptive, and cogent notes. She dramaturged all my productions while here at Arena Stage, at NYU, the Acting Company, and from as far as Cape Town and Tokyo, Berlin, Madrid, and Vancouver. Despite a horrific argument many years ago over my wanting to work independently elsewhere and her insisting I stay within the company, I would capsulate that argument. She had been avoiding me for several weeks. I wanted to sit down and talk with her about my next steps after leaving Arena Stage. She came up with many excuses about not making the appointment: “I had to have my hair done...I need to meet with a board member...I have to go grocery shopping.” Finally, I called her and she picked up the phone and we started to argue, and we really went at it.

In the midst of it she said, “I won’t be treated like a four-letter expletive.” And I replied, “Well, I won’t be treated like a four-letter expletive.” And it went on, and it escalated. I finally said, and I can’t believe I had the audacity, to say it even now. I said, “Zel, I just want to be released. I want to be free from the Arena Stage plantation.”…I know…So, goodbye to the four- and five-letter expletives, on came locusts out of the mouth, curses and expletives that I had never heard before. She elevated by going into Shakespearean cursing, curses from Chaucer, curses in Yiddish, curses in Russian, and then suddenly the phone dropped on the table, and there was silence. I could hear the heels of her shoes clicking away until they faded, and then silence. The silence was agonizing. In that silence I said to myself “What do you think you’ve been doing? You have been hurling expletives at the Chanel suit-wearing mafia queen of the regional theatre movement. Your life is over!”

She returned to the phone, and said “I had to put the phone down because someone entered the room.” And I asked, “Who?” She answered, “Al Schneider.” I asked, “What do you mean?”

Zelda explained,

Al and I fought just like this. And I haven’t had a fight with anyone since then. We fought in the parking lot. We fought in the office. We fought on the phone. We fought at lunch. And Al would always say it’s not personal and I would tell all, “Oh no, Alan, it’s very personal.” Putting together a production is very, very personal. Outside of my family, it is the most personal thing that I will ever do.

And so we fought. Zelda wasn’t ready to let go of that argument. She said to me,

I’d like to help you leave Arena Stage. After you visit the prop shop and they take off your chains and shackles, come to my office and I can give you some start-ups, right here in the district, in Virginia, and in Maryland. In the suburbs, there are all these theatres popping up—dinner theatres. I think they call them “beef and boards.” I’d like to write you a letter of recommendation. You can always do The Good Person of Szechuan, while serving Szechuan stew. Or you can perhaps do Dinner at Eight, although their dinner starts at five and six; so it’s not to interfere with coffee and dessert during the second half of Death of the Salesman. I’d love to write that letter for you. I’ve been told that I have a very good turn of phrase, and when I write a letter it’s not head-to-head automatic, I put everything I can into it, because Taz, you should have a career that you want and deserve.

I stayed on, and I stayed on…and I stayed on. It was the best decision Zelda ever made for me.

‘It happens to most of us. Somewhere in our lives it happens to most of us.’ And I said, ‘Zel, you’ve never been fired.’ And she said, ‘Taz, I’m not most of us.’—Tazewell Thompson

I was once working with a student designer at NYU and the student designer, months ahead before the first rehearsal, she and I were not seeing eye to eye at all. I would bring in research, and she would bring in research that had nothing to do with my research, or the homework that I had given her. It was not working. I went to Zelda, she sent me to the design department and we talked and we tried to make it work with the design student, but it was just not going to work. I finally insisted, bringing Zelda and the design department together, that we all know that this was not going to work, and something must be done. The student was replaced. A week after that in rehearsals, I was feeling very guilty and I visited Zelda’s office and I said, “I feel terrible. A design student—a student—has been fired because of me.” And she said, “It happens to most of us. Somewhere in our lives it happens to most of us.” And I said, “Zel, you’ve never been fired.” And she said, “Taz, I’m not most of us.”

Zelda: complex, tough, tender, inspiring, imaginative, inventive, erudite, difficult, unique, caring, loving, political, brilliant, brave, bold, tenacious, remarkable, renegade, witty, relentless, stylish, classy, resilient, empathetic, fallible, uncompromising, vulnerable, visionary, vain, genius, magician, phoenix, soulful, raved, romantic, transcendent, and splendid.

And now all the planets have crashed, and the whole world has shifted. Out of a chaotic sky and the times teeming with lightning, leaning in sorrow in the saddened aftermath of your passing, artists are left dashed, shocked, and shivering, fending for ourselves, reaching for the eternal dream, and the transcendental light you left us. How are we to catch our breath again?

From Walt Whitman:

We receive you with free sense at last, and are insatiate henceforward;

Not you anymore shall be able to foil us, or withhold yourselves from us;

We use you, and we do not cast you aside—we plant you permanently within us;

We fathom you not—we love you—there is perfection in you also;

You furnish your parts towards eternity;

Great, or small, you furnish your parts toward the soul.

The soldier's pole is fall'n;Young boys and girls are level now with men;The odd's gone;And there is nothing left remarkable beneath the visiting moon.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here