A Lover's Guide to American Playwrights

Edward Albee

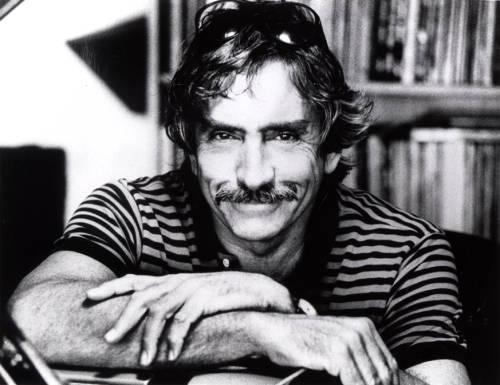

Edward Albee is famous for despising being eulogized. So here goes: a salute to the living, breathing, writing Edward Albee.

Edward Albee is a playwright who has done everything wrong. He has written the wrong plays at the wrong time for the wrong kind of stages. He has imagined for himself the wrong kind of career—one that can never exist in the American theatre. He has staked his money on a sucker’s bet, supporting a profession that has, by many accounts, been dead or dying for years. Edward Albee—a man who never got the memo.

Here’s the memo he didn’t get. Date: 1958. To: Young Master Albee. Re: “The Playwright’s Life— Rules to Live By.”

- Avoid experiment. American audiences have no stomach for it.

- Avoid other writers. The playwright is a solitary beast. No good can come from helping them. They only want what you have anyway.

- Find a style of writing that works for you, and stick to it. Longevity in the arts is our ongoing love affair with the familiar.

- Exercise moderation when writing about reality. Sure, everybody knows the world can be brutal and harsh, but it doesn’t help to dwell on it. The Greeks were the biggest dwellers of all, and what have they done lately?

- Avoid, when possible, unpleasant characters. Particularly avoid the following: vulgar, mouthy drunks—especially women; aggressive strangers who hang around park benches; unforgiving, unloving mothers; and married men who fornicate animals.

- Forget about animals altogether. Nothing bores an audience quicker than long speeches about people and dogs or cats or, whatever, goats.

- And for god’s sake, stay away from dressing actors up as animals. Someday someone’s going to write a play about Lizards and then we’ll know it’s all over.

- Leave ideas to the Europeans.

- Leave Broadway to the British.

- Simplify, clarify, and explain. It’s even good to have a character spell out the meaning of the play—a friendly narrator type, you know, voice of the playwright kinda thing.

The memo goes on, this list of the rules that Edward Albee missed. And then there’s one final one: "There are no second acts in American life, especially in the theatre. Once you’re written off, it’s impossible to write yourself back on."

We celebrate Edward Albee because he has done everything wrong, because he missed the memo. He is the counter-example as great example, the artistic contrarian in an age of corporate sameness. We celebrate him because he grabbed hold and shook us out of our complacency when he was a thirty-year-old playwright and because he never let go.

A carelessly dressed guy, fallen from physical grace, approaches a man on a bench, head buried in a book. “MISTER, I’VE BEEN TO THE ZOO.” It’s the ur-Albee moment: the stranger from nowhere forces the complacent man to look up and take notice, forces all of us to take notice. Can you remember the impact of those words the first time you heard them? Will you ever shake the hangover from that angry, debauched exorcism of a party that leaves George and Martha alone—guests gotten and gone, imaginary son dead? Or can you drown the quiet echo of their final moment, as George sings, “Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf…” And Martha responds, “I…am…George…I…am.” Can you lose the sad chill of the moment in A Delicate Balance when Harry and Edna show up on their best friends’ doorstep, frightened, terrified of, precisely, nothing, and move in, with their terror, with their nothing?

How can those of us who work in the American theatre make it possible for more writers to do what he has done, to do so much wrong so well... How can we embolden them to build bodies of work this varied, probing, vital, and fine?

One of my revelations from rereading Albee’s plays has been how deeply they run in me, how physical the memory of them is. They seem to travel under the skin, through the blood, along the frayed ends of nerves. Where, in us, do plays live?

A woman who is three women, at 26, 52, and very old, watches her own death, denying it, accepting it, welcoming it all at once, until it seems that death is in the room with us, too. A missing maybe baby, a slaughtered lover/goat, a lady who claims to be a dying woman’s mother—his plays work on us like personal traumas, sending out aftershocks of recognition. Recognition of ourselves.

Edward Albee’s dramatic problems—the ones the plays set out to tackle—are never less than problems of existence. Death is everywhere in the plays. Our days are played out in its waiting room. Palpable, literal death and its cousins: silence, absence, emptiness, loss. How do we live in the presence of death? And how do we love?

Albee’s plays are crammed, mangled with love. This phrase from A Delicate Balance hangs over his work for me: “love and error.” Think about his characters—couples, lovers, sisters, friends, parents, children, even strangers and animals. They drive the ones they love away or love them too little, too meanly, too distantly, destructively, or just wrongly. Love and error. It is, as the woman says in The Play About the Baby, “a wangled teb.” Edward Albee is our great anti-romantic poet of love, its rhapsodist and coroner, performing his playful, furious autopsies on it—revealing the existential terror of our intimate relations.

How can those of us who work in the American theatre make it possible for more writers to do what he has done, to do so much wrong so well—to make such an impact? How can we help them range this widely and freely for this long? How can we embolden them to build bodies of work this varied, probing, vital, and fine? What more can this theatre community do to encourage the early attempts of our playwrights? What more can we do to sustain them as they write their ways from their own Zoo Story or Death of Bessie Smith towards a Virginia Woolf or Delicate Balance? What can we do to ensure that they have a second act or third or fourth to reap the fruits of their artistic maturity?

Frankly, I look at the example of Edward Albee, like that of O’Neill before him, and worry that such a career isn’t possible anymore, certainly not on Broadway, not even on regional stages. I fear that we’re too adventure averse, too nervous to commit to more than one play at a time, too apron-tied to the thickest critics and the conservatism of an aging audience. But we want to make it possible.

What’s the answer? Again, Edward’s singular career offers one: produce more new plays, more early-career playwrights. From 1963-1971, with two producers, Richard Barr and Clinton Wilder, Edward did something that I’m not sure has been done before or since. He sunk profits from his Broadway hit Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf into producing the plays of other young writers. And so, through the Al-bar-wild Playwrights’ Unit, the world was introduced to the brilliant idiosyncrasies of Sam Shepard, LeRoi Jones, Adrienne Kennedy, Terrence McNally, John Guare, Frank Gagliano, Lanford Wilson, Lee Kalcheim, Megan Terry, and others. Albarwild—it sounds like some art-radical jungle beast, and it was. As if that wasn’t enough, Edward Albee, the very model of the playwright at his most individualistic, started a foundation for writers and artists of talent and need. He fixed up a barn for them to work in, a center for “creative persons.” He runs it to this day.

I haven’t seen a memo from Edward Albee or anything like his rules for writers, but I can pluck some principles from the example of his art and life. Try these:

- Never stop exploring, even at the precipice

- Defy expectations, especially your own

- Don’t accept no

- Write about big things, even if you set your plays in living rooms

- Write great roles, then find great actors to fill them

- Find producers who believe in you—not just in one play, but in all your plays past and future. Stay with them

- Let your subconscious be your guide

- Read great plays and then write them

- Read great playwrights and then become one

- Hang out with composers, poets, painters, sculptors and other writers

- Love form and play with it

- If you make any money, spend it to support writers you believe in

- There are writers around the world being silenced. Visit them. Hear their stories. Fight for their freedom

- Tell your truth

- And this from The Play about the Baby: “Always be precise: saves time, saves paper.”

In the last minutes of The Zoo Story, Jerry provokes Peter to pick up the knife he tosses him. Then he runs onto the knife in Peter’s hand. It is, like so many Albee endings, a moment of intense, quiet intimacy. Jerry thanks Peter for comforting him and, we suspect, for the sheer contact, this last stab at something like love. You have to start somewhere, he has explained, if not with people, then with animals. If not in life, then at the moment of death. Jerry is death’s suitor, and he’s chosen Peter to show him to the door.

This is where Edward Albee started—his pen, Jerry’s knife. And we will run onto the blade again and again for as long as he chooses to put work into the world. He insists on contact, especially with ourselves. He gives us the gift of our own fear.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Yuck.

Compelling. Something I've always wondered about Albee more than any other writer I've wondered about is what is it like to have your work celebrated then shunned then celebrated. And through it, to go on. That takes a combination of persistence, guts and faith.

Thanks, Todd London. That's going up on the bulletin board!

You just jump started my Monday. Brilliantly said. Words to live by.