A Man For This Season

On Ben Foster’s Monstrous Stanley Kowalski

There are few stage and screen performances so tied to one actor as Marlon Brando's Stanley Kowalski. It's the role that made him a star and, much like Laurette Taylor's performance of Amanda in The Glass Menagerie, the actor was able to wrestle the character away from Tennessee Williams and make him entirely his own. Thus, while Blanche DuBois has become, in layman's terms, “the female Hamlet,” a role open for re-interpretation and coveted by actresses of a certain age—the role has been played by Vivien Leigh, Jessica Tandy, Jessica Lange, Ute Hagen, and Natasha Richardson on Broadway alone, each of whom has helped plumb deeper into the dazzling Belle Reve belle—Stanley has constantly been reborn in Brando's image.

The recent Young Vic production of Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, which opened in London last year and just transferred Off-Broadway to St Ann's Warehouse in Brooklyn, is a radical rethinking of the Southern playwright's classic. Director Benedict Andrews has turned the material inside out, not only offering us the entire production in the round on a revolving stage, but in modern dress. When Gillian Anderson's Blanche wanders into the theatre wearing Jackie O sunglasses dragging a designer rolling suitcase behind her asking for Elysian Fields, we know we're witnessing a Streetcar unlike any other. Anderson is a beguiling Blanche, embodying the frayed fragility of the Williams heroine without undercutting her own self-delusions, alcoholism, and unrepentant resilience. She’s a basket case that knows her life to be one of performance—it’s no surprise that the stage begins to revolve once she takes her first sip of alcohol, so intertwined is her headspace with the sparse and near-antiseptic Kowalski apartment in front of us. As the show progresses, the set becomes a mere Ikea-decorated blank canvas onto which strewn clothes, broken glasses, and discarded party favors are thrown and dumped haphazardly.

In Andrews’ and Anderson’s hands, A Streetcar Named Desire emerges as, more than ever before, a play about abuse.

In Andrews’ and Anderson’s hands, A Streetcar Named Desire emerges as, more than ever before, a play about abuse. And adding to that is a fascinating take on that “Polack” Kowalski. Ben Foster's Stanley is a brute—not (just) in Blanche’s eyes, but also very clearly in the audience’s. When he talks of the Napoleonic code, he strikes us as an ignorant, sexist pig; there's no charm to sugarcoat his misogynist drivel, no twinkling eyes or cad-like candor to make us smirk at his own silly pronouncements.

Where Williams’ text (and Brando's incandescent performance) celebrates Stanley’s raw masculinity—you definitely don't question why Stella would forgive this man for all his missteps—Foster and the Young Vic production almost go in the opposite direction, making Stanley always already an insufferable guy. Williams’ stage directions all but conjure up a seductive force: Stanley Kowalski “is of medium height, about five feet eight or nine, and strongly, compactly built. Animal joy in his being is implicit in all his movements and attitudes.” Because of the recurring animal imagery Williams provides for Stanley (“feathered male among hens,” “baying hound”) you’re supposed to be drawn to him as a force that’s magnetic. But in the half a century and change since Brando made his mark on the character, the many Stanleys that have come since have succeeded or failed by trying to match that animalistic allure that so defines the character on the page.

Stanley, we’ve been taught, needs to first earn our lustful leers before he shocks us with the intentional cruelty he imparts on Blanche. Even a cursory look at the many actors who have played Stanley on stage gives you a sense of what often is embedded in casting the wild Williams “brute.” Look at the parade of matinee idols: Anthony Quinn, Aidan Quinn, Blair Underwood, and Alec Baldwin. The latter even earned a rave from the New York Times: “Unsurprisingly, Mr. Baldwin imbues Stanley with an animalistic sexual energy that sends waves through the house every time he appears onstage. The audience responds with edgy delight from when he first removes his shirt and unself-consciously uses it to wipe the New Orleans sweat from his armpits and torso.” Less successful in comparison tend to be the Stanleys—like that of John C. Reilly in a 2005 staging—that don’t immediately demand your, in current internet parlance, thirst.

This is what makes Foster’s take on the character so fascinating. Devoid of the usual, now “period,” costume trappings that have made the play a quintessential mid-century classic, Stanley’s demeanor and dialogue feel even more outdated than Blanche’s Southern belle posturing. Anderson makes her Blanche a woman out of time, trapped in clothes and an apartment that suggest she should get a better, fairer shake, while Foster really dives headfirst into everything that makes his Stanley a “walking ape,” a vision of an ossified vision of masculinity.

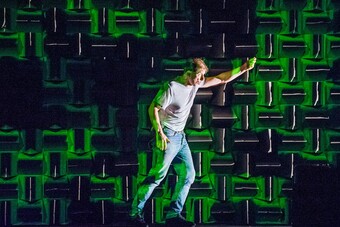

Given his attire (Tommy Bahama shirts over a wife-beater along with cargo pants and flip flops), his tattoos, and his demeanor, he's the type of guy you wouldn't be surprised to find out was a Trump supporter. His muscled “compact” body feels like a threatening force and the frisson of sexual energy emerges when he prowls around in his Under Armour underwear as more an affront than a seduction. His is a masculinity that lures almost in spite (and not, as in Brando or Baldwin, because) of itself. It’s a tough angle to play because it undercuts much of the tension at the heart of Stella’s plight. But the beauty of this approach, and of Andrews’ production, is its unabashed embrace of Blanche’s point of view.

Where Williams’ text demands you see Blanche and Stanley’s dynamic as a sexually charged tete-a-tete—“I called him a little boy and laughed and flirted. Yes, I was flirting with your husband!” Blanche tells Stella at one point in the play—their rapport isn't sexually charged here. Blanche's ingratiation doesn't feel like flirtation so much as defense mechanisms that she's fully aware are falling on deaf ears. Gone is the coquettish trill of her words when addressing Stanley—the one she successfully deploys with Mitch—and in its stead is a cautious performance of femininity designed more for herself, for us, than for Stanley.

Even the climax of the play, when Foster's Stanley picks up Anderson’s Blanche (in a ridiculous pink-tulle dress and matching rhinestone tiara) and slams her down on the bed he shares with Stella, is played less as a jolt than as a silent abdication. Whereas we've seen Stanley and Stella lustfully make love on the floor of their apartment, there's no luridness to this rape scene. Stylized, the moment becomes all the more painful to bear—Blanche’s world slows down for us, creating a revolving tableau, as if she’s already dissociating from what’s going on around her.

Foster’s portrayal of Stanley confronts audiences with his contemporaneity—this is no archly poeticized vision of an ape-like man whose emotions get the best of him, but an oft-fetishized vision of masculinity that’s been stripped bare; all that’s left is the virile toxicity that has marred countless Blanches and Stellas in its wake.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here