A.R. Gurney

Saved by Off-Off Broadway, Back on Broadway with Love Letters

Photo by Gregory Costanzo for Signature Theatre.

More than a decade ago, A.R. Gurney, who had written some forty plays over forty years, wondered whether he would be forced to retire. “I thought I had told the world everything I wanted to tell the world.” But even when he did finally come up with a new idea, he couldn’t find a producer or theater interested in it. Now, at age eighty-three, Gurney has shows in both the new Broadway season, and the new Off-Broadway season. Revivals of two of his plays open within the next two weeks—Love Letters on Broadway, and The Wayside Motor Inn Off-Broadway. He has become a playwright-in-residence at the Signature Theatre, which has committed to two more of his plays, including a new one entitled Love and Money.

Ask Gurney what happened to change things around, and his answer is succinct: Off-Off Broadway saved him.

From Sondheim to The Flea

The majority of Gurney’s most successful plays, such as The Dining Room and The Cocktail Hour, have established him as the foremost playwright to (as he puts it) “explore, examine, criticize, and even say goodbye to what is known as WASP culture—the kind of upper middle-class white Anglo-Saxon world that I grew up in.” But that is not how he began in the theater. Gurney originally wanted to do musicals. Stephen Sondheim, a couple of years ahead of him at then-all-male Williams College, had turned the annual jokey college revue into a real musical, for the first time casting female performers from nearby women’s colleges. Gurney, inspired and instructed by Sondheim, took over the spring musical when Sondheim graduated. Then, when he enlisted in the Navy, Gurney was put in charge of musical productions to entertain the sailors on a naval carrier. When he enrolled afterwards at the Yale School of Drama, he put together a musical entitled Love in Buffalo with a cast that included Dick Cavett, and came up with the idea of doing Shaw’s Pygmalion as a musical, but was shot down—many years before Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe created My Fair Lady.

Gurney originally wanted to do musicals. Stephen Sondheim, a couple of years ahead of him at then-all-male Williams College, had turned the annual jokey college revue into a real musical

“That’s all I wanted to do in life was write musicals,” he says now. But it is one thing to write musicals; another thing to have them produced. “Nobody wanted to do them. So, I thought, I’ll try my hand at plays.”

Gurney’s playwriting began as a sideline. He took a job teaching literature at M.I.T.; “I had enough time to begin to write short plays.” It was only with the response to The Dining Room, several decades after he began, that his plays paid off enough for him to quit M.I.T. and move to New York to devote himself full-time to the theater. But even then, he says, his plays needed work; they had a “skit-like quality,” each play more like a series of short sketches. “It took a little while for me to be able to run with a play that told a complete story.”

By 2001, he thought he had run out. But then September 11th happened. Gurney was driven to write a political play, O Jerusalem, which included a sympathetic Palestinian character. “My usual venues didn’t want to touch it,” he says. “But then I got a call from my pal Swoosie Kurtz who was performing in a play called The Guys downtown at a joint called the Flea Theater”—an Off-Off Broadway theater founded by Jim Simpson and his wife Sigourney Weaver. Anne Nelson’s play commissioned by the Flea and directed by Simpson, focused on a fire department captain trying to write eulogies for those in his firehouse who had died on September 11th. “It was such a strong, simple response to the recent disaster, and worked so well in that intimate space,” Gurney says, “that the next day I sent my own play on to the director.” Thus began a collaboration that has yielded eight new plays so far (the latest Family Furniture last year), all of which Gurney describes as “somewhat political.”

“Several other plays of mine were performed elsewhere during that period. Yet it was the Flea that gave me the energy and love of the profession which I thought I had lost.”

Gurney’s Signature Season: The Wayside Motor Inn

When the Signature asked Gurney to become a resident playwright this year, he was delighted at the offer, but hesitant about the two plays they had chosen to revive. Both The Wayside Motor Inn, which opens tonight directed by Lila Neugebauer, and What I Did Last Summer, which will run in May directed by Jim Simpson, “have rather checkered careers in New York,” Gurney says.

Gurney wrote The Wayside Motor Inn in 1977 as what he considers a series of sketches that tell five different stories of people who are staying at a motel outside Boston. But, while the five pairs of characters are in separate rooms, the five pairs of actors are performing simultaneously on a single set.

As his friend Holland Taylor has pointed out, Gurney “has done some sort of trick, some sort of conceit in every play he writes.”

“The Wayside Motor Inn was dismissed by the critics when it opened, and it’s never really worked before,” Gurney says.

Yet at early rehearsals for the new production, he says, he objected to the new approach that the director and designers were taking. “I said ‘Oh, we’ve got a lot of work to do here’—not in the writing but in the staging. It is too dark. It is too this, it is too that. What I was trying to do was impose a kind of old-fashioned conventional way of doing the play.”

The creative team persisted with their ideas—more subdued lighting, a less busy set. “I did not want to yell and scream, so I went along. And I’m delighted I did. It works in a way the original play did not.” Gurney attributes this in part to “a change in the culture; audiences are more able to absorb five different plots simultaneously.” He also sees the experience as an example of the advantage of working with younger people. “Their energy, commitment, and sense of originality—and their defiance, if that’s the right word—are contagious.”

Love Letters and Broadway

Love Letters, which is receiving its second production on Broadway, is an exception in Gurney’s career—and something of a fluke.

“I’ve had very little success on Broadway,” he says. Despite his high profile and prolific output, only three of his plays have wound up on the Great White Way, none lasting more than a few months. “I normally do not write for Broadway; I don’t like it. If someone has to pay one-hundred and fifty dollars, it puts a particular type of frame around the play—the emphasis on a large cast and elaborate costumes and scenery in order to make the customer feel as if he’s gotten his money’s worth. I am not comfortable with that.”

Yet, his simple play, where two characters read letters they write to one another over half a century, is opening September 18th at the Brooks Atkinson Theater with considerable fanfare.

Why its commercial appeal? “It’s easy to do,” Gurney says. “It doesn’t require a lot of rehearsal; for older actors it doesn’t require memorizing: they can read the script. There’s a universal theme—a love affair.”

That helps explain why, according to the Broadway production press release, since 1988, Love Letters has been translated into twenty-four languages and produced in more than forty countries.

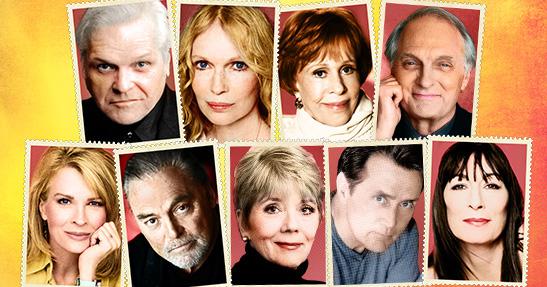

One suspects its appeal for Broadway has most to do with the cast for the new production being made up of rotating pairs of well-established stars: first, Brian Dennehy and Mia Farrow, then Carol Burnett with Dennehy, followed by Alan Alda and Candice Bergen; Stacy Keach and Dame Diana Rigg; Anjelica Huston and Martin Sheen.

If some might label this stunt casting, there is what you could call an organic history to this set-up.

Love Letters started as an exercise; Gurney was teaching himself how to use a computer. Eventually, he considered what he had put together as a short story, and submitted it to the New Yorker magazine. “They sent back a rejection, saying ‘we don’t publish plays.’ My agent said ‘Maybe it is a play.’”

Gurney had his doubts, and asked Holland Taylor to read it with him at a benefit at the New York Public Library. The response was such that it was produced on stage.

“Some early critics dismissed it,” Gurney says. “They didn’t think it was a play either.”

It premiered in New York at the Off-Broadway Promenade Theater in 1989, with John Rubenstein and Kathleen Turner, but it was only performed on Sundays and Mondays.

“Elaine Stritch came to me, and said ‘I want to be in that play of yours,’” Gurney recalls. “I didn’t want to say, ‘you might be a little too old.’ I said ‘who would you do it with?’ She said, ‘I already found someone. Jason Robards wants to do it with me.’ So I told the producers.” That was the beginning; by the end of the run, some fifty stars had taken their turn playing the parts.

Advice for Younger Playwrights

Gurney’s account of his playwriting career seems colored by the man’s modesty, but, when asked what advice he would give to young playwrights, he’ll admit to having learned a few things since writing what he considers his first serious play almost sixty years ago, The Pig Sextet, based on John Cheever’s short story “The Day The Pig Fell in the Well”:

I think the thing I learned most over the years is how, once you decide to write for the theater—with people sitting in sometimes uncomfortable seats—you’ve got to move it along. Every piece of dialogue must be as essential as you can possibly make it, and the less significant speeches must be cut. It’s harder for younger people to see that. Once you’ve figured out what you want to have happen—the action—then all of the dialogue, everything the characters do, should relate to that action. You shouldn’t get off track and write a nice little scene that does not have much to do with that action.

It’s important to pay attention to the earlier stages in the developmental process. If you got a reading, keep an eye on the audience—see when they begin to look at their watches; when they shift in their seats.”

On the bulletin board outside the theater where The Wayside Motor Inn is playing, there are several quotations by Gurney, including “All really good theater has an element of anarchy underneath,” along with another that references “the abyss.”

“I’m not sure what I meant,” he says with a laugh, but then elaborates:

The theater is such a deliciously artificial form and you are imposing a kind of order on chaos. This seems most evident in the theater. It’s not like fiction, not like a novel, where you can go wherever you want, have as many people as you want. It’s confined. The restriction of drama makes me at least aware of the underlying abyss.

Abyss or not, Gurney keeps going.

“I think it’s very good that he cannot stop writing,” says Molly Gurney, his wife of fifty-six years, with whom he has four children and eight grandchildren. “It keeps him busy.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here