By Blood a Queen, In Heart a Clown

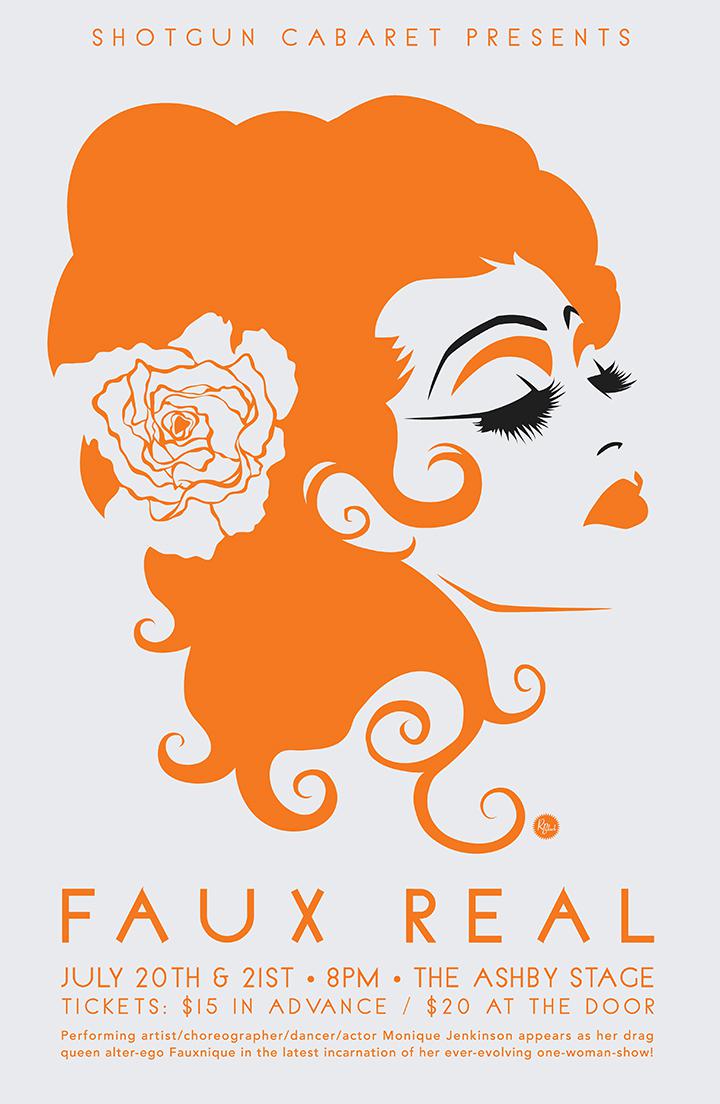

Beyond the Façade of Shotgun Cabaret’s Faux Real

It was my own fault really. An email mix up, not marking the right date on my calendar, general absent-mindedness… Looking back, it seems fitting that I stumbled into Shotgun Cabaret’s showing of Faux Real, written and performed by Monique Jenkinson, long time Bay Area and international performer in Berkeley, California on one of the theatre’s traditional dark nights under the misguided notion that I would be seeing a revival of Caryl Churchill’s seminal play Top Girls. A one woman cisgender drag show, (meaning a show in which a female who identifies as a woman performs as a fictional, exaggerated extra-feminine persona) and a play detailing the lonely-at-the-top position of a female executive in the 1980s on the surface might not seem all that similar, yet, at their core, both probe at the cost of sacrificing one’s femininity for success. The key difference, however, is that Top Girls is a constructed scenario, poking at truth through a series of narrative tableaus impossible in the real world, while Faux Real traffics in the currency of a true to life personal story, navigating the complicated world of drag as a cisgendered woman, told by the very performer who lived her own story. Whereas Top Girls deals with an external success, defined in the outside world by the measurable standards of career, Faux Real treads lightly on the questions of living your truth and exploring the singular journey of a specific person—a far more internal, personal kind of victory—and one that’s much harder to judge by any outside standards.

In Faux Real, the performative elements are thoroughly entwined with Monique Jenkinson’s own life story, eliciting an empathy and engagement from the audience that transcends the normal construct of narrative theatre (where the actors are playing nothing more than a part). Here, the part Monique plays (her drag queen alter ego Fauxnique) extends beyond the theatre to her entire life. Conducting the crowd like at a gospel revival, eliciting cheers and echoes of agreement from what I could only surmise was a local audience made up of those already familiar with Jenkinson’s work, the performance seemed elevated by the demonstrated power of a sympathetic and participatory audience. That power, I found, wasn’t so much held in the suspension of disbelief, but in an interest in reality and the ability to allow a performer honesty, which this audience valued above the technical presentation. Sure, there were dropped lines, accidental prat falls, and bad costume changes, but, the story and staging was transcendentally human, seemingly in line with the shows essential ideology: Stripped away from the façade of polished theatricality, authenticity—even when jarring—is still beautiful. In telling her story, Fauxnique’s humanity sat front and center, inviting compassion from an audience that had to sit through more than a few lip synching numbers that seemed at odds with the touching journey of her own life. And yet, it has consistently been acts of self-expression like this that have been changing the culture from twenty feet back for years. One lip-synching number of Aretha Franklin’s “I Say a Little Prayer,” where Fauxnique chooses to play the part of the backup singers, seems a fitting illustration of this sentiment.

As LGBT people move toward a position of societal equality, will drag mean what it used to?

Shotgun Players in Berkeley, CA, has long been a staple of the Bay Area theatre scene, coupling ambitious staging with the work of bold playwrights, both new and established. However, what separates Shotgun Players from the majority of Bay Area theatre companies is its willingness to provide a stage to those underworld artists and performers, vaudevillians and poets that wouldn’t otherwise be likely to fit into a mainstage season. By showcasing scenes from the underground on their dark nights, as opposed to simply shuttering the theatre each Monday and Tuesday, Shotgun Players keeps the local scene from congealing in its own homogeneity, and allows performers, like Jenkinson, access to the audiences and opportunities they deserve.

As an outsider looking in on the world of fetishized female clothing, lip-synching, and tales of gender confusion (or in this case, certainty), the narrative journey of Fauxnique’s self realization of drag destiny seemed as far away from my own personal experience as could be. However, what became immediately accessible was her (ironic) story of a failed audition for the Broadway production of Rent.

Rent was my first exposure to drag, albeit a form of drag that struck the right musical cues and forced its audience, often of peppy, middle class teens, to empathize with the romantic representations of outcasts, poor starving artists, or gender bending drag queens. Having only previously experienced a pre-aestheticized, palatable for suburban taste and mass consumption kind of drag, Faux Real asked whether or not I could appreciate the real thing. And this seems to be the essential theme of the show and the tension that the artist exploits capably, if uncomfortably, in asking her audience if it has the strength to look past the romance of the other and wholeheartedly embrace veracity with the same arms that open wide so easily for prepackaged representation. Fauxnique puts as much effort into communicating her truth as she does into living it.

With the recent federal legalization of gay marriage, what do drag performances like this mean politically? Historically, one of, though certainly not the only, reasons drag has been a staple of LGBT culture is due to the vicarious thrills a closeted audience could receive from a performer who was expressing a freedom they were denied. As LGBT people move toward a position of societal equality, will drag mean what it used to? Jenkinson’s own story seems to offer an answer: Drag may no longer be as politically resonant as it once was, but what will continue to push the needle toward broader acceptance, compassion, and empathy are people, like Jenkinson, who continue to express their own confusing, seemingly contradictory truths bravely. Faux Real shows us that the abstractions here, the personal, difficult authenticity of the life behind a performance, provides its audience with more value than the tired face value staples of a drag show ever could. Faux Real is more real than Faux, and for that, it is more than worthy of the respect it demands of its audience, and ultimately, receives.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here