Can Tadeusz Kantor’s ideas about death be revived in theatre about dementia?

The word “dementia” unfortunately carries many negative connotations. It activates the imagery of depersonalization, loss of dignity and integrity, and desolation of relationships to the outside world. Can the issues brought about by this group of disorders be translated into theatre, giving the difficulties in communicating a condition known to few other than those directly afflicted by it?

The answer may reside with a theatre practice that was birthed out of the twentieth century European political turmoil. Theatre of Death is a theatre tradition created by Polish artist Tadeusz Kantor as a reaction to World War II. Perhaps one of his most memorable works is the performance “Dead Class,” where he burdened actors with corpse-like mannequins. Some of the more significant questions that Theatre of Death asks have stuck with me, such as, “Is the relationship between life and death really viewed objectively and truthfully?” and, “How do humans fit into these two seemingly separate states of being?”

It is through this questioning of philosophical assumptions about mortality that dementia can enter the stage. Those who have witnessed the terminal illness of a family member or friend know what I mean when I say that a dementia patient exists in a state of limbo. They exist in a balance between life and death, where to transition from the first to the second requires long-term processes, such as physiological changes in the brain, as opposed to an immediate transformation. Although Kantor probably did not touch upon dementia as an area to explore with Theatre of Death, I used his ideas in my work on a piece called “Range of Distress.”

In this work, I tried to make a distinction between what dementia is subjectively and objectively from an observer’s perspective. From an outsider’s point of view, the dementia patient is seen as alive or dead, depending on their physical state. Using Theatre of Death logic, this would be argued to be subjective, as the conclusion reached by the observer through their observations. This view would therefore be untruthful, based on Kantor’s belief that humans are not a “truth-telling representation.” The more objective view of dementia would instead see dementia as the process or limbo state I mentioned earlier, as Kantor criticized the definition of life as a category by stating that it had been “reduced to a banal slogan.”

Some of the more significant questions that Theatre of Death asks have stuck with me, such as, ‘Is the relationship between life and death really viewed objectively and truthfully?’ and, ‘How do humans fit into these two seemingly separate states of being?’

These questions about how dementia is viewed can be explored further through the psychological conflict experienced by dementia patients. This psychological conflict includes how they view themselves and if this has changed because of their illness. These experiences of psychological conflict may be easily relatable to a wide audience, as most will have experienced challenges related to identity, especially in relation to establishing and maintaining independence. But when it comes to bridging a dialogue between the psychological conflict and the physical manifestation of the diseases, the depiction of dementia may become problematic due to ethical issues.

For one, the topic is highly sensitive, as dementia is a class of diseases that to a great extent are fatal. This may lead to psychological harm towards audience members, through emotional distress. Therefore, the portrayal of dementia must be done in a carefully calculated manner, to avoid distress that crosses the line to what is ethically justifiable. That is not to say that theatre about dementia cannot be portrayed with the intent to stir any form of reaction; not doing so would deprive the topic of any discussion or thought, and wouldn’t provide for communication between those afflicted by it and others.

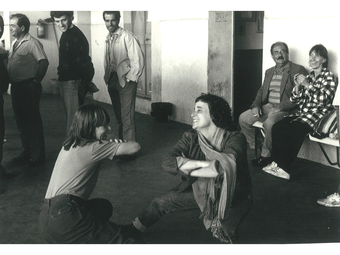

“Range of Distress.”

On the other hand, when I first encountered Kantor’s Theatre of Death, I realized that there was a way to portray dementia which both respects and neglects ethical considerations in a way that nourishes theatre. This realization came through observing that I could address another ethical issue, namely the stigmatization of mental and psychological health. In my country, Sweden, there has been great debate about mistreatment within healthcare that has lead to unnecessary deaths. Combined with social stigma of having a disease, the image of dementia patients has become infected with stereotypes and negative attitudes about elderly people, such as “old people are weak.”

I found that a way to relieve these attitudes, and at the same discuss dementia, was to exaggerate them. I created a character, using Kantor’s dead-like facial makeup, who appeared monstrous and grotesque through the combination of appearing apathetic and making choking noises, as if disconnected from a respirator. This drooling character reinforced all the negative attitudes about dementia patients, including the lack of individuality—of being “one in many.” It was only when this character was awakened from their zombie-like trance to interact with a baby doll that the audience could catch a glimpse of the person that used to be. This interaction was a reminder of the loss of positive relationships by the dementia patient, as a result of circumstances over which they exerted no possible control.

I believe that others can apply the ideas in Theatre of Death to theatre about health, even outside its presumed political parameters. Dementia can be theatrically realized, as the consequences of it are beyond medical or personal; it is externally defined by social norms of behavior and detrimental attitudes about aging. Theatre of Death can transcend its political context, and reach across to encompass the social consequences of dementia.

***

Sources

Juntunen, Jacob. “Presenting Death: Uncanny Performance Objects in Taduesz Kantor’s Dead Class.” Retrieved from http://www.academia....

Kantor, Tadeusz, and Michal Kobialka. A Journey through Other Spaces: Essays and Manifestos, 1944-1990. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here