Community Legacy is “Inherited” in Matthew Lopez’s Play

Matthew Lopez’s intense theatrical two-parter The Inheritance seeks to cover considerable ground in its six-plus hours. It’s a play that owes a lot to the gay stories that came before it—Angels in America, The Normal Heart, As Is, Love! Valour! Compassion!—but one that roots itself firmly in today, in both form and content.

The Inheritance, which ran at the Young Vic in London earlier this year, and transfers to the Noel Coward Theatre in the West End in September 2018, tells the stories of gay men today and the stories of a community’s past, specifically focusing on the AIDS crisis. At the heart of the uncovered narratives is a quartet of relationships: Eric (Kyle Soller) and his vain boyfriend Toby (Andrew Burnap); Eric later taking up with widowed older man Henry Wilcox (John Benjamin Hickey); Toby pursuing actor Adam (Samuel H. Levine); and Toby pursuing Adam’s troubled doppelganger Leo (also Levine). Surrounding these men are their friends—an often indistinguishable lineup of men who drop in and out of the narrative to flesh out this slice of contemporary New York life.

The play is a very loose retelling of E.M. Forster’s masterpiece Howards End, which centers on a failed love affair and a promised inheritance of the family home. Lopez transposes the complex family narrative to the group of gay men, thus queering Forster’s narrative and providing parallels between the rigid social norms of Edwardian England and the inequalities that have endured in contemporary society. Alongside this, Lopez makes Forster (Paul Hilton) himself the play’s narrator. The character, who was kept in the closet by the era he lived in, tells the story of hiding his identity throughout most of his life. And, throughout the play, he also interacts with the contemporary characters, who allude to the continued threat of homophobia and hostile political climate of America, and offers commentary on their lives. This plot device becomes complex and affecting as Forster’s own story is told. Astounded by the freedom the young men have—his own life of having had to supress his desires—acts as a profound counterpoint to the sexual freedom displayed by the characters he guides.

Lopez transposes the complex family narrative to the group of gay men, thus queering Forster’s narrative and providing parallels between the rigid social norms of Edwardian England and the inequalities that have endured in contemporary society.

This paralleling of Forster’s novel, Lopez’s adaptation of it, and Forster’s own life is a complex narrative line, but one that is effective. It communicates the essence of what Lopez seems to be trying to do: showing the lineage of gay stories. From Forster to Walter to Eric, there are three generations of gay men exposed to different challenges, all trying to find their place in the world. What Lopez touches on effectively is the conflict between thinking rights and equality have been won and whether or not they have been.

On top of the multiple story lines, the actors double up on roles. What is a simple practicality also allows for commentary through these performances. Hilton’s doubling as Forster and Walter gives a historical commentary on a community of gay men, and Levine’s doubling of Adam and Leo gives Lopez scope to comment on different sides of gay experience today.

Adam is a successful, somewhat egotistical actor with a vast amount of privilege, while his “other half” in Leo is that of a conflicted young man troubled by drugs who is forced into prostitution. For all of Adam’s privilege, moving with ease in a world that accepts him, Leo is another side of gay men, one still afraid and struggling in life. Though there is much in Lopez’s somewhat idealized version of New York that can be critiqued in terms of showing a narrow slice of gay life, the use of Leo as a glimpse into another experience acts as a counter to that.

The long play could benefit from some paring back, and, when examined up close, it has problematic elements in areas of diversity and representation, with the cast being largely white and almost universally upper-middle class. The inclusion of a woman so late in the narrative is jarring—there is next to no mention of the women of these men’s lives until then—and it creates questions around the role of women thus far overlooked, overshadowing the moment.

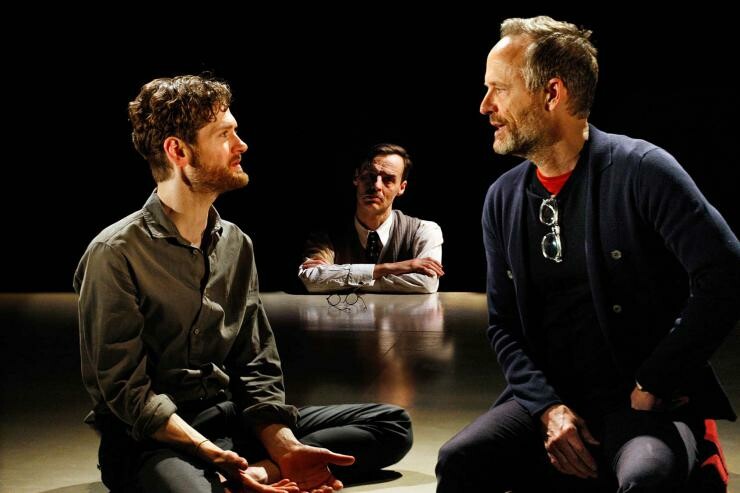

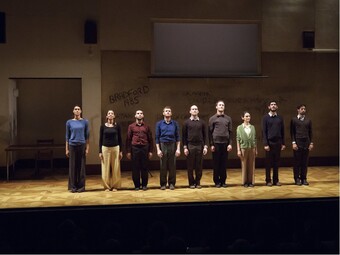

Under Stephen Daldry’s precise directing, the actors spend almost the entirety of the play on stage, sitting on the sidelines during the scenes they aren’t in, as if bearing witness to the stories of others, and occasionally interacting with the action from their position. This adds to a feeling of a shared experience, with both each other and the audience. Daldry pairs his direction with a stripped-back design—a simple platform stage that rises and lowers—and minimal props. A doll’s house, standing for the inherited property, and a cherry blossom tree, planted in commemoration of AIDS victims, are revealed for short moments behind the backdrop and create striking, symbolic effect.

In The Inheritance, Lopez explores the legacy of the AIDS crisis. The timelines of the characters who lived through it cross; encounters with the younger generation allow older individuals to pass their stories on or expose their scars. In representing what was lost and what was gained from the epidemic, Lopez truly delivers. This is most striking at the end of Part 1, when Lopez creates the most moving moment in an AIDS drama since Larry Kramer threw milk across the stage in The Normal Heart: Eric visits the house where Walter nursed his friends with AIDS. He stands alone, reflecting on the stories of the rooms. Slowly, from the auditorium, men dressed in 80s clothes, played by actors we haven’t seen before, filter onto the stage. They introduce themselves to Eric and each other. They are the ghosts of the men who died, who lost their fight, and they fill the space until the lights go out. It is as near perfect a theatrical moment as could be wished for.

There are philosophical moments that evoke Kushner’s musings in Angels in America, and, the most obvious comparison to Angels: the play’s length, ensemble nature, and momentary supernatural and Brechtian elements.

What’s missing in the play, though, is a real tie to HIV today. There is one instance—affecting and poignant in and of itself—of an HIV scare for Adam. But it happens in isolation, with little repercussion character-wise and in the wider community. If it is a deliberate construct—the idea of a forgotten inheritance—it is one that sidesteps what Lopez’s seems to be aiming to do: memorialize and educate, but also celebrate where the community is today.

The idea of “inheritance” moves beyond the content of the play—Lopez also demonstrates his own inheritance from the gay playwrights who came before him, specifically those who wrote on the AIDS crisis: Kramer, Terrence McNally, William Hoffman, and, of course, Tony Kushner. References to their texts are woven in: the use of Forster as a narrative device echoes Kramer’s ‘I belong to a culture’ speech, in which he lists the influential and often-hidden figures of gay history; the rural retreat where gay men went to die echoes McNally’s comic-tragedy Love! Valour! Compassion!; the urgency of the politics and the anger against the current regime is pure Kramer. There are philosophical moments that evoke Kushner’s musings in Angels in America, and, the most obvious comparison to Angels: the play’s length, ensemble nature, and momentary supernatural and Brechtian elements. The Inheritance is nowhere as fantastical, or indeed political, as Kushner’s epic, but despite the comparisons Lopez isn’t rewriting Angels, he’s offering a response.

For those familiar with the source material, the moments in The Inheritance that speak to them are highly emotive. There’s perhaps a whole generation of gay men who might miss the shades that come through because they did not live through the crisis or have not see the work borne out of it. But for a generation who didn’t experience the epidemic firsthand, Lopez offers a way in. And it is a fitting one.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here