September 2011

Global temperature yearly average: 0.63 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels

Sometime between my trip to Alaska and the premiere of Sila, between environmentalist Bill McKibben’s call for “art, sweet art” and scientists’ warning to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, I have to do something becomes I have to do more. In my search for what that might mean, I land on the idea of writing a series of related plays. Since there are eight countries in the Arctic—United States, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia—I will write one play for each country. At first, I don’t say this out loud. The only playwrights I know who are writing plays in series are not just men but famous men: August Wilson (Pittsburgh Cycle), John Guare (Lydie Breeze Trilogy), Sam Shepard (Family Trilogy Cycle), Robert Schenkkan (Kentucky Cycle). Who am I, a young female unknown, to embark on such an ambitious project? Eventually, I muster the courage to say it out loud—until I’ve said it enough times that I start to believe myself. My series will be called the Arctic Cycle.

The idea of a series is appealing for several reasons. I’m craving the long-term commitment to an idea that allows for deep exploration. I’m interested in the story a body of work can tell in addition to the story each individual play tells. And because of the time it will take to complete all eight plays, assuming that I do, this work will hopefully bear witness to the massive changes taking place all around us in a way that hasn’t been done before. Perhaps that has some value.

April 2016

Global temperature yearly average: 1.03 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels

In a fit of rebellion, I publicly break up with Aristotle. If content truly dictates form, then the dramatic structure we, in the United States, have been predominantly using over the last fifty years is inadequate. After Sila, and after a series of trips to Norway to write and develop Forward (the second play in the cycle), I’m becoming aware that we cannot use the tools of yesterday to tell the stories of today. Or as Einstein famously said, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Our world is vastly different from the worlds of Aristotle and Freytag. It is vastly different from the post-World War II economic boom and middle-class expansion era. “Stories work with people, for people, and always stories work on people,” writes sociologist Arthur Frank. We can’t advocate for a shift in beliefs and values—a shift that would support a more just and regenerative world—through means that have traditionally served to reinforce the colonial, patriarchal, and extractive status quo.

Forward, which unfolds over 120 years, premieres at Kansas State University in February 2016. Building on my exploration of form in Sila, which features multiple storylines and more-than-human voices, the play presents a poetic and humorous history of Norway—from the initial passion that drove explorer Fridtjof Nansen to the North Pole to our present-day anxiety over the rapidly changing climate. Nine actors play forty-plus characters. There are no polar bear puppets this time but Arctic sea ice is embodied and expresses herself through song. A student involved in the production, whose family was dismissive of climate change, expresses how working on the play changed his outlook and influenced his family’s behavior.

What do you do when the thing you’ve been fighting for disappears from under you? Is writing plays really the answer?

Sometime in 2019

Global temperature yearly average: 0.98 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels

By now, not only is my entire playwriting career focused on how climate change is impacting our lives, but I also serve as artistic director of the Arts & Climate Initiative, an organization whose mission is to use storytelling and live performance to foster dialogue about our global climate crisis, create an empowering vision of the future, and inspire people to take action. There is no doubt in my mind that culture is one of the best tools we have to shape our future and I’m determined to enlist as many theatre artists as I can to tackle this herculean task.

But.

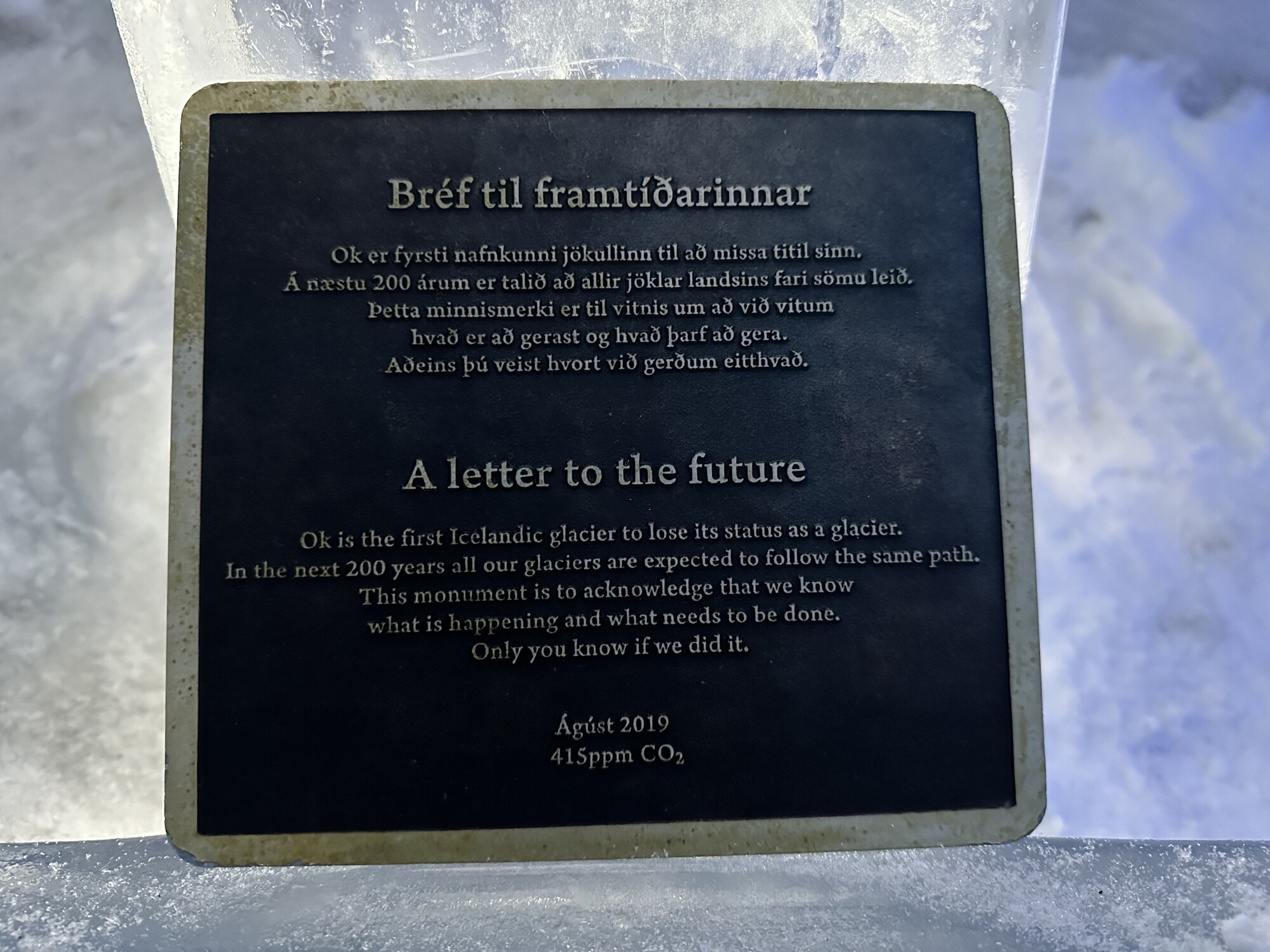

Was it a slow dawning? A single event? At some point it hits me: oh, we’re not going to make it. I realize, based on what scientists are saying, that the much hoped-for 1.5 degrees Celsius upper limit of global warming, which I have organized my thinking around, is going to come and go in my lifetime. It took us too long to take action; there is no staying below the amount of warming that is considered “safe” anymore, at least not without dubious carbon-capture technology that doesn’t exist yet. The Anthropocene is here to stay. Glaciers will melt. Seas will rise. Cities will bake or flood or both. Rivers and lakes will dry. Millions of people will be displaced and species will continue to die. What do you do when the thing you’ve been fighting for disappears from under you? Is writing plays really the answer?

October 2017

Global temperature yearly average: 0.95 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels

The pandemic hasn’t happened yet. My existential crisis hasn’t happened yet. So much hasn’t happened yet. But what has happened is Hurricane Harvey making landfall in Texas and Louisiana in August, causing catastrophic flooding and killing more than a hundred people. As the character in No More Harveys, a play I haven’t written yet, says:

First, it was Harvey the hurricane. When it hit Texas a few years ago, I spent days glued to the TV, obsessing over the news. I don’t live in Texas but for weeks afterwards I dreamt of biblical floods, floating furniture, and wet cats.

Then in October, eighty women make allegations of sexual harassment or rape against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. Later, I write:

Then it was Harvey the Hollywood producer. When it was revealed that he had been assaulting women for decades, I went down a rabbit hole of #MeToos and ate nothing but ice cream for weeks.

The convergence of these two Harveys is so monumental to me (who do you think dreamt of biblical floods and ate ice cream for weeks?) that I wait for some smart journalist to draw the connection… but no one does. Yet these Harveys perfectly illustrate the consequences of a system gone awry and its impact on the most vulnerable among us. Always, those with money and power are free to prey on others—be they people with marginalized racial identities, women, or ecosystems.

April 2022

Global temperature yearly average: 0.91 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels

No More Harveys, commissioned by Cyrano’s Theatre Company, premieres in Anchorage, Alaska. Somehow and despite the pandemic, I have managed to pull myself out of the existential crisis that threatened to swallow me in 2019 and written this play, in no small part thanks to the support of a community of artists (and scientists) who believe the arts have an important role to play in addressing the climate crisis. Yes, we will most likely go over 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming in my lifetime but any fraction of a degree that we save protects us from the worst. And so, the work continues.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here