Exiting and Assessing Impact in Community-Based Theatre

This is the sixth and final post in “A Balancing Act: Community, History, and Playmaking,” a series taking an in depth look at the process, start to finish, of working collaboratively on a site-specific theatre project with a community to animate a historical site. This series will explore some of the challenges of including all stakeholders, communicating a clear vision, translating work to non-arts partners, and balancing history with compelling storytelling.

Many artistic projects thrive without any formal assessment, but in the case of community-based theatre, there are often specific goals and intentions that can be reflected upon. When we first assembled to assess the impact of Animating the James & Ann Whitall House at Red Bank Battlefield, we focused on formulating how to best measure if the project achieved the goals of the community’s commissioning body. While we entered the evaluation process confident in the experiences and impact we had observed, we worried whether the data would convey similar results or be useful at all—the future of the project depended on what we discovered. Given these perceived dangers and challenges, we may not have engaged in our evaluation if the commissioning body didn’t request it. But what began as an obligation, concluded with a wealth of information and knowledge that propelled this project forward. We realized that evaluation could be a critical partner in understanding the impact and developing our work, and this all began with asking the right questions.

Evaluation can be seemingly useless and laborious when practitioners fail to perform it in their own interest. By this I don’t mean that they fail to stack the deck, or cater the design of their measurements to the areas in which they believe they can succeed. More commonly, practitioners are apt to structure and formulate evaluation systems based on what they believe others want to hear, missing an opportunity to ask questions that will aid in their reflection and assessment of meeting the project’s goals.

Evaluation can be seemingly useless and laborious when practitioners fail to perform it in their own interest.

Asking the right questions begins with identifying those goals. Throughout our process, we identified four key goals:

- Generate more traffic to the James & Ann Whitall House and surrounding battlefield

- Connect community members with their local history,

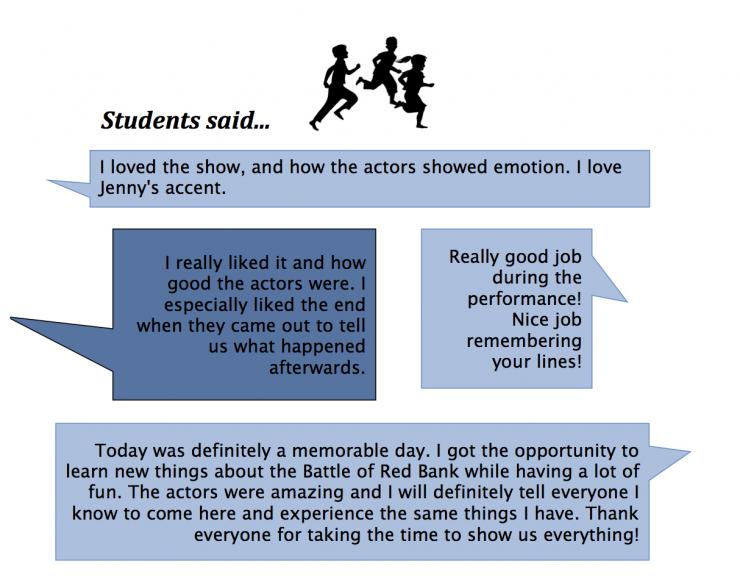

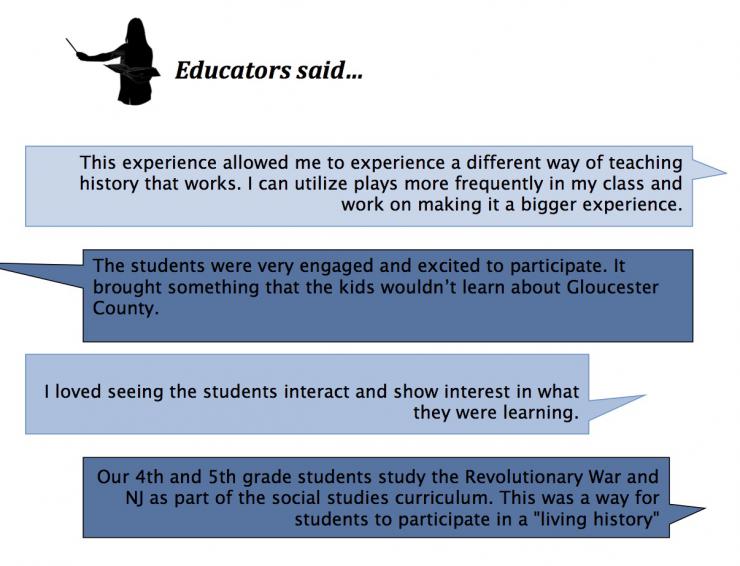

- Share the local history with students and educators, and

- Foster a sense of community pride around the contributions of southern New Jersey to the Revolutionary War.

Once we identified our goals, we needed to determine whether they would be measurable. Many of these goals would be difficult to finitely measure given the time and resources available, as well as the need to find relevant indicators for each.

An indicator is a specific and observable element or characteristic that indicates a goal has been met. The challenge of using and measuring indicators is they require a lot of time and resources to truly assess. For example, an indicator for reaching Goal 2 could be the number of audience members who volunteered at the James & Ann Whitall House, or other local historical sites and societies. To measure this, we might keep a record of all audience members and continually cross-reference it with volunteer sign-ups at any local historical establishment. This requires the support and resources of other establishments, which could take months or years to measure, and only pertains to one indicator. In short, it’s unfortunately not sustainable for a project of this magnitude.

As much as we would love to understand the impact with this level of detail, we had to work with the resources and time we had. Therefore, we developed an attitudinal survey to allow audience members to report their thoughts, feelings, and attitudes towards various statements that corresponded to each goal. Audience members responded to each statement on a Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” For example, we asked audience members to share how much they agreed with the following statement in relation to Goal 3: “I understand the importance of this site and the events here in the context of the Revolutionary War.” There are limitations to using an attitudinal survey; it’s not the same as giving a history test that measures fact-based learning. Instead, participants self-report, but this type of survey can still provide valuable information about audiences’ experiences.

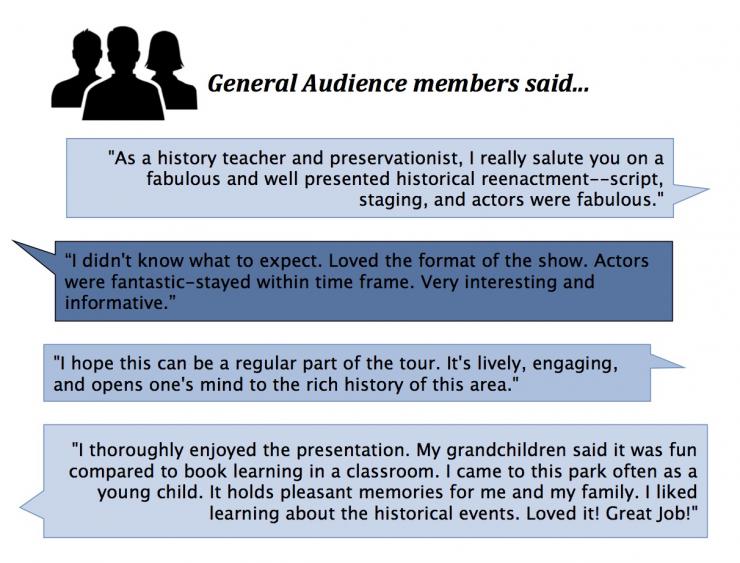

To complement our assessment of the goals, we collected relevant demographic information that could provide deeper insight with other data points. For example, we asked audiences to indicate if they visited the Whitall House prior to the performance; we then analyzed the responses of first-time visitors and returning visitors separately. One of our concerns was whether the experience of the play overlapped too much with the regularly scheduled programming at the site. However, our analysis revealed that the experience was just as engaging and informative for those with and without a previous visit to the site. Additionally, we were interested in assessing the aesthetic experience because there was significant concern about whether the non-traditional, promenade presentation of the play would be well received by the community, particularly non-theatre goers. By asking people to share how often they attend theatre, we found little difference in the experience for theatregoers and non-theatre-goers alike, which confirmed the piece was inviting and accessible to all audiences. In conjunction with our data collection, these demographic questions provided a thorough and nuanced picture of the performance’s impact.

After collecting our data, one question remained: what would be the future of this project? Community-based arts projects face a unique challenge in maintaining their impact after the practitioners and organizers move on to other projects. Community members, educators, and students universally expressed interest in seeing Animating the James & Ann Whitall House continue, but there are still many questions about how to make this happen. When we performed the play, we coordinated many components of the production, including casting and directing the actors, hiring the stage manager, selecting costumes, and navigating the logistics of the day. We had enormous help and support from the community, but their vision of a subsequent performance involves the same process. We would love to continue the project, but want to ensure it has a sustainable future that is in and of the community. We want all community members to feel ownership of this incredible experience they supported, helped advise, and shepherded into existence. We know this may take time, but we hope that the experience of developing and seeing the play opened a window of possibility to the future.

Community-based arts projects face a unique challenge in maintaining their impact after the practitioners and organizers move on to other projects.

Contemporary artist Alfredo Jaar discusses the importance of revealing these future possibilities through absence. In one of his most famous projects, Jaar noticed that the Swedish town of Skoghall, built by the paper industry, had no cultural spaces. In response, he created a paper museum, invited Swedish artists to exhibit their art, and then burned it to the ground twenty-four hours after it opened. Although Jaar was clear about his plans, this burning created outrage. Once the community caught a glimpse of what a cultural center could add to their town, they wanted it to be a permanent fixture. Jaar opened up the possibility of a community cultural center by making the absence of one visible. For him, an absence is not tragic, but is filled with hope and potential. This potential was reached seven years later when the community invited him back to design a permanent structure.

Today, the Whitall House remains open and continues to receive visitors as it did before our community-engaged theatre project. We hope that our approach to animating the site and its stories helped reveal the great opportunity for arts programming in the community, and the value of honoring the historical stories of the site. Even if it takes many years, we hope the community will continue supporting this project and others like it, and lead the charge to celebrate and preserve their local, cultural capital.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I loved reading about this work. Thoughtful, honest evaluation really is crucial for understanding, measuring, and sustaining impact over time, as I've seen working with many arts organizations doing similar research (using WolfBrown's Intrinsic Impact program). Too often this reflective, evaluative step of the artistic process is skipped because conducting audience research seems too daunting or resource-intensive, so it's really heartening to see other artists engaging in this kind of work. Liane, congrats on the successful project and assessment process! I'd love to chat sometime and learn more, particularly about your use of the impact data and how you approached the analysis process.

Thanks, Sean! I completely agree. While possibly intimidating at first, evaluation can be such an invaluable tool, no matter the size and scope of the project. For us, it really affirmed the connections we had made with the community and gave more specific details on the experience of various demographics than we could have intuited from observing and speaking with audiences alone. I would love to chat sometime and share more about this work and how we collected and analyzed our data. I'm a big fan of the depth and detail of the WolfBrown system, so I would love to hear more about your work as well.