Feeling Something

Creating Visceral Theatre

I invited Lucrecia to share thoughts on community and audience participation for this series on Designing Women, since we are both fans of La fura dels baus’s work in Barcelona. We also have our work with Pregones Theater in common. We have similar tastes in theatre and value that important relationship that is carefully built between artist and audience through performance. She is a sensitive and smart designer; a real instigator. I had the pleasure of collaborating with her on grant application that we did not receive. For some inexplicable reason, we clicked. Crossing fingers that we get to play together soon. —Regina García

Not long ago, a friend and I went to see An Octoroon, written by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. It was an extraordinary experience: the play was outstanding, the performances and direction were insightful, and of course, the design was intelligent and attuned to the ideas presented by the playwright. As I walked away, the main thing that stayed with me was the last line of the fourth act: “Anyway, the whole point of this thing was to make you feel something.”

I was not manipulated into emotions, although in these times it’s hard not be emotional when seeing a play about race. But I was reminded that my senses—all of them—exist to make me feel something. Towards the end of the performance, a flat drops abruptly, and its sound and airstream made the entire audience jump in our seats. Suddenly, and without expecting it, I was made to physically taste cotton balls. Feeling simultaneously powerless and suddenly present to feel something, I was reminded how amazing theatre can be.

Can I rewind eighteen years?

I was a young theatre student backpacking through Europe, and, in one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences, I found myself in at the Arene in Nimes, watching a group of performers, La Fura del Baus, performing for my all senses for the first time. I do not remember the play well, but I do remember this complicated machine, a hybrid industrial fan with a lot of metal adaptors. They added large bottles to the machine and suddenly, the troupe led the audience into a journey of fantastical smells: fresh cut grass, bubble gum, cow’s shit, pizza, etc. The audience was transported by the smells. The smell of cut grass reminded me of home; the smell of cow’s shit brought me back to my grandfather’s farm. My senses were very much in touch with personal history and this performance had the power to bring those memories out. I left the Arene in tears, longing for home.

Lighting designers are visual dramaturgs: we create environments, give context to the performance, and every night we set the show in motion. We create a multifaceted relationship with directors; we are partners in every way.

Fast-forward eighteen years: a career as a performer transformed into a life in lighting design. Lighting designers are visual dramaturgs: we create environments, give context to the performance, and every night we set the show in motion. We create a multifaceted relationship with directors; we are partners in every way.

I have been thinking lately about design as a medium for artistic dialogue with audiences. I have been trying to put into words what exactly I want to achieve, but I find it hard to do so. I am always in awe of the artistry and thoughtfulness in my colleagues and collaborators. In the past few years, I have found very rewarding relationships with various artists that are looking to cross boundaries and create work not just for, but with their audiences.

I met Eamonn Farrell and his company, Anonymous Ensemble, while touring Mabou Mines’ DollHouse and immediately felt kinship. I started designing for the company in 2008, and we have grown into creating complex relationships with our audiences. In Liebe, Love, Amour, we asked a young student to tell us which spice would she be if she could choose one. She answered, “Cinnamon!” I was running the board that day, and I clearly remember how touched I was by her answer. It felt so tangible. I remember feeling like I was back in Nimes, smelling cinnamon all over the Arene. More importantly, I felt that here was an audience member that was not afraid of engaging in a role to help us and enrich our storytelling.

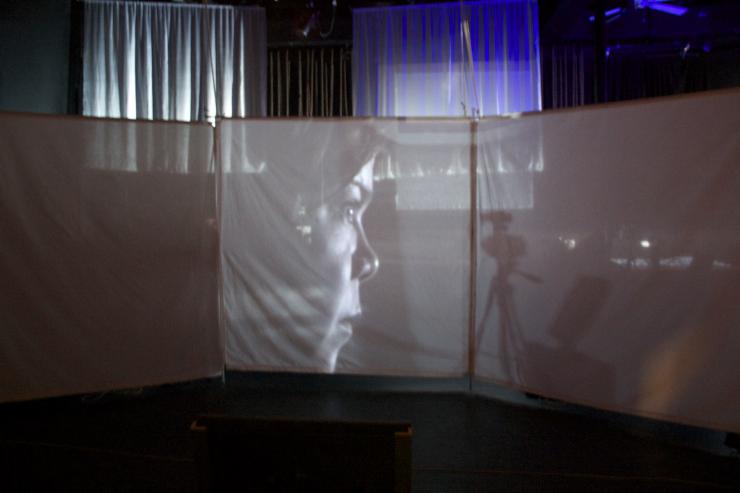

A few years later, we stepped into a very thrilling relationship with our audiences with a piece called I Land. We wanted the audience to essentially create the performance without performing it. We started the show by asking the audience questions for forty-five minutes. Simple questions like: Do you know the story of your birth? Can you tell us about your first kiss? It was exhilarating to find new answers and new takes on life every night. We created a transcript template and input their answers verbatim, shaping a new narrative for each performance. We could always feel the audience having a visceral response. Not always friendly, but they were always present. My design felt very engaged as well—maybe not as clean and polished as I would normally like, but it was definitively very resourceful. We used handheld devices, conventional lighting equipment, and even mobile phones to light scenes. We left all artifices open and completely unmasked. Actors were able to make decisions about how to use the lighting equipment and frame the storytelling every night; in many ways, it was out of my control. We did endless workshops of how to touch a light, how to focus a light, how to compose with scenery, and how to move with a light and its angle to tell a story. I still was able to control its intensity through the board, but its compositional assertion was done within the stage proper. It was a definitively thrilling prospect to watch “my” design transform every night.

Anonymous Ensemble’s next step will involve crafting a new show in which the audience decides the route our characters take. As a designer, I would like to have the audience involved in the visual narrative of our work. I want them to transform us, transform themselves, and create a new story every night. I hope that includes the audience making design choices for all to experience. It might sound like a logistical nightmare, but I wonder what type of work might come out of it and how different generations react to it.

One piece that inspires me is Josh Randall and Kristjan Thorgeirsson’s The Blackout Experience—an extreme haunted house with a cult following. They based their rapport with their audience in fear and gave it a sexual undertone. Even though I do not enjoy being afraid, I admire their commitment to thrill their audiences every year with a primal emotion. As we are redefining what a theatrical experience is, I certainly would like my work to be able to elicit gasps, screams, and unfiltered reactions from the audience.

Jennifer Tipton is one of the most admired and celebrated lighting designers in the country, and one of her favorite sayings is that ''Ninety-nine and nine-tenths percent of the audience is not aware of the lighting, but 100 percent is affected by it.'' Maybe those percentages should change. Let’s see what happens if we ask the audience, should it be bright? Should it be dark? Should it be loud? Should we experience gusts of smells? Should the smell of cinnamon invade the theatre?

***

All photos from the Anonymous Ensemble Catalog

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here