Gender Parity in Northeast Ohio Community Theatre

During a stint on a play selection committee, a man I consider a friend, as well as someone aware of and knowledgable about diversity issues, scoffed at my suggestion that the theatre produce two female-led plays in the upcoming three/four show season. Certain many of the theatre’s past seasons contained multiple male-led productions, I created a spreadsheet charting the gender composition of the theatre’s playwrights, directors, and casts from 2010 to the present. The results were as I had predicted.

Gender parity in media has received more attention of late, and theatre is no exception.

The League of Professional Theatre Women’s analysis found that women represented an average of 30 percent of playwrights produced by twenty-two Off-Broadway theatre companies between 2010–2015. The Count, meanwhile, reported that only 22 percent of all regional US theatre productions from 2011–2015 were written by women.

In Chicago, women comprised only 25 percent of 250+ non-musicals produced during the 2015–2016 season. And in the San Francisco Bay area, 27 percent of shows produced in 2011–2015 were authored by women. Theatre Communication Group (TCG), the publisher behind American Theatre Magazine, revealed that women wrote 26 percent of the productions in their 411 member theatres in 2016–2017.

I suspected Northeast Ohio community theatres wouldn’t fare much better. After defining the geographical area, Cleveland to the north, Canton to the south, and Youngstown to the east, I identified the theatres and parsed out which fell under the definition of “community.” This included nonequity theatres, those not affiliated with colleges or universities, and those that don’t pay their actors. Interestingly, most community theatres in Northeast Ohio do pay their directors, which deviates from the national norm. The only exception on the list is the River Street Playhouse, Chagrin Valley Little Theatre’s black box, where everybody (including the director) is a volunteer.

I gathered information regarding playwrights, directors, and cast composition from the theatre's website, Facebook, and other media coverage. If the specific production’s cast list was unavailable, I relied on the publisher’s website. Consequently, I couldn’t account for every ensemble member or gender swap.

Statistics were taken from the seasons between 2010 and 2018 (three from 2011), and limited to adult productions. The exclusion of youth productions made the data more comparable to statistics from other studies.

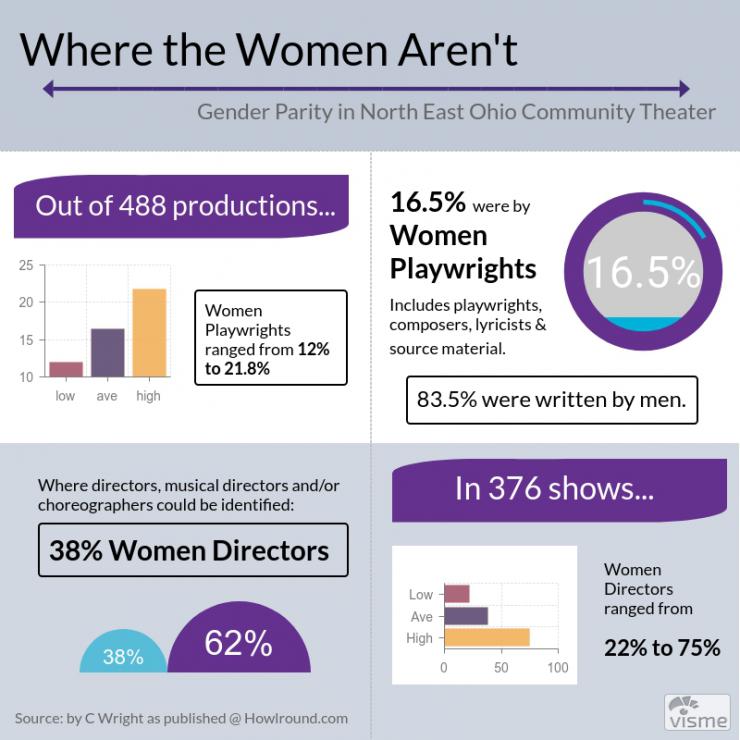

Across fourteen theatres and 488 productions in Northeast Ohio, the percentage of shows authored by women averaged 16 percent, ranging from a low of 12 percent to a high of 21.8 percent. By comparison, a dramaturgy class in Charleston, South Carolina, examined 293 productions in 2015 and 288 shows in 2017, and found 17 percent and 20 percent, respectively, were by women playwrights.

I’m not ascribing malevolence or overt sexism to these numbers. In fact, I suspect the biggest culprit is inattention. Many decisionmakers I spoke with expressed surprise, and variations of “I wasn’t aware of that” when I revealed their specific theatre’s statistics. Most had no knowledge of the national or regional reports at all. That’s disconcerting, but not an indication of purposeful discrimination. When I asked one decisionmaker about his theatre’s (relatively high) inclusion of women directors, he couldn’t name any contributory programs or policies. Frankly, it appears that no one seems to be actively preventing or advocating gender parity at all.

This doesn’t mean there isn’t a significant amount of unintentional obstruction, however. Last summer, for example, I witnessed an artistic director tell a room full of actors how “important” women playwrights were to her. A couple of weeks later, she revealed her theatre’s 2018 season: comprised solely of male playwrights.

I contacted one of this theatre’s board members after the season announcement and expressed my concern. She told me that their artistic directors have “complete control” over production selection, and the slate was only presented to the board as a “courtesy,” not for approval purposes. I reached out to the artistic director for comment on this article, but she never responded.

Research indicates that scripts attributed to female-sounding names are rated lower by artistic directors than identical scripts tagged with male-sounding names. The media characterized this result as institutionalized sexism from female ADs when in fact, the lower ratings occurred when reviewers were asked to predict how others would perceive the script. This includes the likelihood that a script would win awards, or be widely produced, or be received warmly by an audience. The ADs in the study were predicting the world’s bias, not their own.

Given the above, “Men’s plays make more money” as a justification for the lack of women’s scripts and stories makes more sense. Economist Emily Glassberg Sands considered that too, but found the opposite. Not only were plays and musicals by women more profitable than those by men, weekly ticket sales were higher, meaning that women playwrights had greater audience appeal. More surprising, none of these money-making shows were given longer production runs than those by less profitable male writers. Women playwrights were literally held to a higher standard than men.

In general, women directors fared better than playwrights in Northeast Ohio, but still fell significantly short of parity. Of the 376 shows where a director could be identified, an average of 38 percent were women. Comparatively, women directed 36 percent of the plays in Chicago, 42 percent in the San Francisco Bay area, and 33 percent Off-Broadway. NEO community theatre is on trend, but it’s not an egalitarian trend.

There are bright spots, however.

Productions at CVLT River Street have been described to me as “passion projects” or “labors of love.” Unlike many theatres, where a committee or artistic director chooses a season of shows then solicits directors, prospective directors at River Street submit proposals of their chosen scripts, and the committee decides from the pool of proposals.

Since 2010, 75 percent of River Street’s directors have been women. During that same time period, the theatre produced 14.9 percent women playwrights. When I looked at individual seasons, I discovered a demarcation line. From 2010 through 2015, men comprised 38 percent of River Street’s directors, and produced 4 percent women playwrights. For the past three seasons, 100 percent of River Street’s directors have been women, and the production of women playwrights increased to 28.5 percent.

River Street’s cast composition jumped too; from 45 percent women in the 2010 through 2015 seasons to 60 percent in more recent years. Since 2010, the theatre has averaged almost 52 percent women, which ties them for first place of the theatres examined.

As mentioned earlier, River Street doesn’t pay its directors. And because it’s a secondary stage, they do have the latitude to produce edgier or less mainstream plays (however they define those terms; see aforementioned research). The CVLT main stage, however, does offer a stipend. And since 2010, 46 percent of their directors have been women, placing them second only to their companion black box.

Elsewhere, another theatre appeared to be backsliding. From 2011 through 2015, 42 percent of the theatre’s directors were women, including two seasons of actual parity. But in the two most recent seasons, the rate dropped to 20 percent. I can’t say definitively what caused this decline, but it does correlate with the appointment of a new artistic director. In fact, she has been the only woman director on the main stage since she assumed her position.

The first…step in reducing gender disparity is not only acknowledging its existence, but admitting inequity is a problem.

Let me be clear: none of the cited research or anecdotes about Northeast Ohio community theatre decisionmakers are an excuse for not putting women in leadership positions. They are simply an acknowledgment that doing so is not a panacea. Besides, women (any minority really) shouldn’t have to bear the burden of diversifying an organization’s product, service or policies. That responsibility should fall to everyone.

The first, rather obvious, step in reducing gender disparity is not only acknowledging its existence, but admitting inequity is a problem. While this sounds simple, a glance at the comment thread of any article that touches on parity/discrimination issues demonstrates otherwise. Passions can run high in all directions, to detrimental effect.

Second is a commitment to change. Again, not so unreasonable until one considers the details. People have adverse reactions to quota systems, which excludes the easiest (albeit imperfect) method of ensuring playwright parity, but relying on our feelings or perception can lead us astray.

For example, women comprise 31 percent of all speaking parts in film and television, a rate that has not improved over the last half century. Geena Davis, the founder of the Institute for Gender in Media, theorized to NPR that this ratio has become our cultural comfort zone, “the norm,” due to generations of prevalence. This perceptual skewing could explain the anecdote I shared at the front of this essay. From my peer’s point of view, a single women-led show, 33 percent of the season’s productions, was acceptable, but two equaled 66.7 percent, and that was just too much. (It also certainly sheds light on the thought process of another theatre’s decisionmaker who told me that a play with fourteen male roles and another with five female roles in a three-show season somehow balanced each other out.)

Could this also be contributing to the dearth of women directors? Perhaps, but again, a blunt policy to “hire more women” could result in the pushback of “they don’t apply,” which may or may not be true. The question becomes: if women aren’t applying at a particular theatre, why not? Maybe the scripts aren’t interesting to the available pool of women directors. Or maybe the problem runs deeper.

Evidence suggests a chicken/egg scenario in which women won’t apply (or stop applying) for awards/grants/positions if they see that women haven’t been chosen or hired in the past. Once an organization is pegged with that reputation, it can be difficult to shake, despite stated commitments to parity and diversity. (Consider a possible favoritism issue too; see below.) Regardless of the situation, it’s the theatre’s responsibility to reach out for talent, not the other way around. This isn’t Field of Dreams.

If women aren’t applying at a particular theatre, why not? Maybe the scripts aren’t interesting to the available pool of women directors. Or maybe the problem runs deeper.

So, what are some concrete steps community theatres can take to improve their gender parity? The Playwright’s Guild of Canada has some recommendations, which include:

- Track demographics about women to assess an individual theatre’s past and present parity, to enable the development of policy, and measure future changes.

- Blind assessments of scripts and applicants whenever possible.

- Provide mentorship to women.

A note on that last one. Some of the community theatres in Northeast Ohio have short (ten-minute, twenty-minute) play festivals, and one recently held a single weekend performance of a local playwright’s short works. However, with the exception of any “contest winner,” the playwrights aren’t being paid. So while encouraging and developing local playwrights is a good thing, it is no substitute for licensing full productions of women-written scripts. Creating a two-tiered system of playwrights, one compensated and the other not, only perpetuates the problem.

Which brings me to the proverbial elephant in the room: favoritism. All theatres and directors battle with this to some degree, and Northeast Ohio is no exception. People prefer working with known quantities. In other news, water is wet. But as Danon Middleton asserts, favoritism can compromise production quality, create an environment of exclusion (see above), limit a theatre’s body of work (e.g., inability to find actors of color), reduce volunteers, and ultimately, lead to declining audiences and revenue (cast members’ family and friends attend performances, after all).

As a participant in Northeast Ohio community theatre, I’ve both benefited from and been disadvantaged by this practice, so there is potential gain and loss for me in advocating its minimization. However, when half of one theatre’s women directors (five out of ten) are the same person, and another follows closely behind (three out of seven), I have to prioritize the integrity of the community over my self-interest.

Community theatre may seem like a superfluous target, or at least not a hill meaningful enough to battle over, but I find that view to be elitist and short-sighted. Former high school jocks join intramural leagues; drama kids grow up and find a community theatre. Tourists purchase 70 percent of Broadway tickets, and those audience members live somewhere. Most people will never see a show on Broadway. They would struggle to afford an outing to Cleveland’s Playhouse Square.

Community theatre is accessible. It is affordable. It is the only version of live theatre most people in this country can access or afford. And that makes it worth fighting for.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Anne Flanagan • a few seconds ago

Terrifically researched article

(if depressing.) Kudos, then, to https://www.harlequinstheat... in

Northern Ohio for producing my comedy Artifice - written by a woman;

starring WOMEN.