Hoping for Change

A Reconsideration of the Hopeless Landscapes of Samuel Beckett

When I was first introduced to Waiting for Godot in high school and again in college, I hated it. I chalked that up to Beckett simply being a little too out there for my liking—honestly, I thought it was just useless chitchat (this came at a time when I was only just learning to appreciate the more traditional works such as Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—my favorites at the time). Later I came to realize that my dissatisfaction lay with the interpretations I was being given—that Beckett was showing a world devoid of hope and meaning, full of desolation and despair. The vast majority of the Beckett criticism and analysis I came upon consisted of deconstructing the nihilistic nature of his work. However, I found it difficult to explain his works so conclusively. One of the most compelling qualities in Beckett’s work is the lack of resolutions—the open quality that leaves many readers and viewers (dependent on the direction, of course) confused about what to interpret. Yet, popular critique often attempts to come up with resolutions that help give us answers, i.e., Godot never comes, thus their waiting is hopeless. Critics have based arguments on resolutions that never actually occur in the text. We never see Godot arrive but what if he does?

Specifically, I struggled to understand how these works could be so definitively categorized as hopeless when the character’s hope continually persists in seemingly hopeless situations. After all, all we have is what is on the page—the characters’ frustration, their persistence, and the hope that drives their stories forward. Within the many open spaces that Beckett purposefully places—those where answers or resolutions are not given—lay possibility, even for the remote possibility that things may change. I seek to challenge the conclusive arguments and assert that we must approach such open writings with equally open interpretations.

When Martin Esslin formulated the Theatre of the Absurd, the theatre movement that expresses the belief that existence is meaningless and hopeless, and applied those interpretive conventions to Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and Endgame, people were finally able to find some meaning in these mysterious dramas. Scholar and critic Peter Boxall analyzes the movement saying, “Fairly quickly after Esslin’s categorization of Beckett’s plays in terms of a brand of populist existentialism and a formulaic dramatic nihilism, both audiences and critics became much more comfortable with the drama.” People could finally place his works into an easily understandable category. Yet, this interpretation negates the open moments that make these works unique.

Much of the nihilistic interpretation hinges upon the idea that the characters’ actions are futile in a meaningless world wherein situations repeat themselves without end. However, this argument supposes that these situations will continue, as they have, forever, which is an assumption. No matter how hard we try to come up with possible resolutions (whether they be definitive or not) and, thus, possible meanings, we forget that the meaning will never come from moments that we assume will happen—such as the idea that scenes will continue, as they have, forever. When asked what he meant by his work, Beckett simply stated, “I meant what I said.” He would frequently deny answering questions about his work because it is not about whether Godot shows up or not; Beckett showed what happened at the end of his play and we can only draw conclusions from what he has given.

There is hope, meaning, and a general something amongst the desolation—a sense of moving about in the night, a sense of having to go on, a sense of having to escape distress.

While Beckett was notorious for not speaking about his own work, there are a few comments, mostly recorded by others, which we can draw on for a hint of guidance. Lawrence E. Harvey, a personal friend of Beckett’s, made an effort to record a few conversations he had with the writer. One specifically speaks to the despairing quality of Beckett’s work:

When asked about the sense of nothingness in his work, Beckett responded that it is more—or at least he moved directly into this related theme—a sense of “restlessness, of moving about in the night.” Much of this is to be found in my work, he said. There is none the less the sense of having to go on.

Beckett did not feel that his plays should be interpreted as nothingness—as he says, “a sense of restlessness, of moving about in the night.” This interests me because it shows that despite a seemingly hopeless fate, there is still the sense of needing to continue. If it were truly hopeless, why do the characters continue to act? In those moments, I find persistence of hope.

While Waiting for Godot could be seen as a play about two men waiting for something that will never come, it is probably more accurate to say that it is about two men waiting for something they keep hoping will come. They continue to hope for salvation even though they are continually disappointed by the lack of results. The best example of this can be found at the end of both acts. Throughout their waiting, Vladamir and Estragon talk around and around about whether they should keep waiting and, ultimately, the end of each act holds the answer to what prevails in them. Each act ends the same way:

Act One:

…

Estragon: Well, shall we go?

Vladimir: Yes, let’s go.

[They do not move.]

Act Two:

…

Vladimir: Well? Shall we go?

Estragon: Yes, let’s go.

[They do not move.]

These identical moments come after they’ve waited for Godot and found out from a messenger boy that he will not be coming today but he will surely come tomorrow. Regardless of their despairing dialogues throughout the play, ultimately their final action to remain is what is important: “‘Shall we go?’ ‘Yes, Let’s go.’ (They do not move.)” Despite wanting to leave, to abandon their search, they do not move—they feel a sense of having to remain with their waiting. If it were definitively hopeless, we would see that Godot never shows up. But we don’t and we never will. We can’t assume he shows up, we cannot assume anything unless it is given by Beckett. While yes, the chances don’t seem high that Godot will present himself, all we are provided is the chance, the small hope that things will be different.

Within the many open spaces that Beckett purposefully places—those where answers or resolutions are not given—lay possibility, even for the remote possibility that things may change.

Similar to Waiting for Godot, Endgame could be taken as the portrayal of the hopeless and meaningless lives we lead because in the end, there is only desolation. However, I choose to look at two small moments in the play that may lead us to a different conclusion. Based on the concept that four people exist within a room when the outside world is pure desolation, we get glimpses of what could exist outside through Clov’s inspections at the window. In these moments, we have hope for Clov, who without hope for the outside world, has no reason to try to escape his abusive pseudo-master/slave relationship with Hamm. The moment when hope spurs comes near the end of the play, after several unsuccessful inspections at the window, we finally get this:

CLOV:

…

(He turns the telescope on the without.)

Let’s see.

(He moves the telescope.)

Nothing… nothing… good… good… nothing… goo—

(He starts, lowers the telescope, examines it, turns it again on the without. Pause.)

…

CLOV (dismayed):

Looks like a small boy!

…

I’ll go and see.

…

HAMM:

No!

…

CLOV:

I’ll leave you.

We see Clov react with fear and, ultimately, hope that there may be a chance for him in the outside world after all. This leads him to finally tell Hamm, “I’ll leave you.” While we will never know if the boy is actually there, we are given Clov’s hope that he is, which is what propels him forward in the play to finally attempt to leave the room. The question then may be: does he leave?

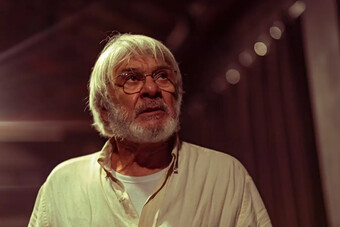

In the photo above, we see the ending of the play. Clov has his bags packed and he has given his final speech. He has the hope that he will escape this place where he has been stuck for so long and this is when lights fade. We do not actually see Clov leave, so that hope that we as an audience have and that Clov has may not be realized; we can never know for certain. We do not get a definitive answer and, thus, we cannot draw a conclusion from the assumption that he never does. All we have is a feeling, the hope that he may go—this open possibility is what keeps hope alive. By acknowledging that it is open, we also acknowledge that hope exists in that possibility.

The popular nihilistic reading does not acknowledge a huge part of these plays—it is too simplistic and, frankly, trivializes the complexities which make Beckett’s work so thought provoking. I am not attempting to say that his works are hopeful, that would be a stretch by any means. I merely want to bring attention to one of the driving factors behind these characters’ actions and, in turn, give recognition to the open spaces Beckett created. There is hope, meaning, and a general something amongst the desolation—a sense of moving about in the night, a sense of having to go on, a sense of having to escape distress. Martin Esslin remembers this conversation with Beckett about why he writes:

Sam told me (and I know he’s told other people) that he remembers being in his mother’s womb at a dinner party, where, under the table, he could remember the voices talking. And when I asked him once, “What motivates you to write?” He said, “The only obligation I feel is towards that enclosed poor embryo.” Because, he said, “that is the most terrible situation you can imagine, because you know you’re in distress but you don’t know that there is anything outside this distress or any possibility of getting out of that distress”—and, if you remember, in Endgame, the question of the little boy that is being seen, Sam had an absolutely mystical obligation towards that poor, suffering, enclosed being that doesn’t know there is a way out.

Beckett felt an obligation to the “poor enclosed being.” However, just because we are enclosed, lost in meaningless movements between birth and death, it does not mean that we exist without hope or possibility. Beckett could feel this obligation because the enclosed being does not know its own possibilities—that it will escape the womb. He is writing about the time when the future is uncertain, when characters may or may not get what they want, but he never definitively gives them either. He writes of an enclosed being, in a purgatory of sorts, waiting, wanting, and hoping to escape. So, who are we to shut down that hope? To assume that this desire is hopeless? After all, the enclosed being does indeed escape the womb…eventually.

Works Cited

Beckett Directs Beckett Endgame. Dir. Samuel Beckett. By Samuel Beckett. Perf. Bud Thorpe and Rick Cluchey. Smithsonian Video, 1992. Web.

Beckett, Samuel. “Endgame.” Samuel Beckett. Ed. Paul Auster. Vol. 3. New York: Grove, 2006. 88–154. Print.

Beckett, Samuel. “Waiting for Godot.” Samuel Beckett. Ed. Paul Auster. Vol. 3. New York: Grove, 2006. 1-87. Print.

Boxall, Peter, and Nicolas Tredell. “First Responses to Waiting for Godot and Endgame.” Samuel Beckett: Waiting for Godot, Endgame. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. 9–50. Print.

Knowlson, James, and Elizabeth Knowlson. “Lawrence E. Harvey on Beckett, 1961–2.” Beckett Remembering, Remembering Beckett: Uncollected Interviews with Samuel Beckett and Memories of Those Who Knew Him. London: Bloomsbury, 2006. 133–37. Print.

Scott, Alan. “A Desperate Comedy: Hope and Alienation in Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 45.4 (2013): 448–60. Academic Search Complete. Web. 12 Sept. 2013.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for the article, Mackenzie.

At one point early on in your piece, you write: "When Martin Esslin formulated the Theatre of the Absurd...people were finally able to find some meaning in these mysterious dramas."

Esslin published his book in 1965, after "Godot" had already been presented onstage for over a decade at that point. By this point, we have the initial performances in Paris (1953) and London (1955) being met with confusion or bafflement, by theater-going critics and audiences alike.

But absent from your essay, in my view, is the exceptional stagings of "Godot" in the US and Europe during this period, which apparently inspired Beckett tremendously (see Knowlson, "Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett," 1996). While critics, the public, and perhaps academicians such as Esslin were scratching their heads and trying to figure out what Beckett was doing in this play, it appears that the thieves, killers, and other criminals staging this play behind bars in Lüttringhausen, Germany (1954) and San Quentin, California (1957) had absolutely no problem grasping the play´s meanings and intentions. (Side note: the 2010 documentary "The Impossible Self" details more about these productions of Beckett staged in prisons).

I think it is important to include this part of Beckett´s history, in terms of analysis and reception. While the intelligentsia did not seem to understand Beckett´s work for some years, "Godot" seems to have been immediately understood by those whose lives exist behind bars.

Further, in making conclusions about the meanings of Beckett´s works, I think it is important to distinguish between the play script, and the performance of the staged version of the play.

Lastly, the play was originally written & performed in French, and during the course of its translation into English (at least), there have been a number of edits, omissions, and debates about which is the definitive manuscript. When referring to specific passages of the play, which edition or manuscript are you referring to? Do you know which Esslin was referring to--the French, the English? Specific productions? All of the above? Which are you referring to primarily in your essay--Beckett´s English translation of "Godot"? Specific productions?

Thanks for the response Brendan! There is so much to say about this topic that I could only briefly touch on in this piece so I'm glad we can go a bit further into it here!

When I referenced Martin Esslin, I did mean that main stream society/audiences/readers were finally able to categorize the works. I am mostly taking about popular theory and criticism. Specifically, I am talking about my experiences studying him in schools where the existentialist and nihilistic interpretations pretty much reign supreme. This is not to say that there are not people that have found other interpretations but, the most common theory out there seems to be one of meaninglessness and hopelessness.

In regards to your questions about text vs staged version: I'm speaking to general interpretations in both. I do tend to find that the same interpretations arise in both forms (of course dependent on the reader and/or direction and/or audience member). While it is very common in literary interpretations, I find that many performed interpretations will leave the same open spaces in which viewers can come fall upon hopelessness. This is why I do try to speak towards interpretation as a whole as opposed to narrowing down to one form.

For passages I am using a more recent edition of an english translation. (For GODOT see my citation: Beckett, Samuel. “Waiting for Godot.” Samuel Beckett. Ed. Paul Auster. Vol. 3. New York: Grove, 2006. 1-87. Print.' for ENDGAME see my citation: Beckett, Samuel. “Endgame.” Samuel Beckett. Ed. Paul Auster. Vol.

3. New York: Grove, 2006. 88–154. Print.) However, rather than specific words, I wanted to pay attention to the actions that are set forth. In Godot, the important thing is that they remain at the end of each act. In Endgame, it is that we do not necessarily see Clov leave but that does not mean that he stays either.

Mostly, I wanted to bring to light my own feelings of dissatisfaction with the more categorical interpretations especially during my education and first experiences with Beckett. I think many audience members (literary or performance) may get turned off early on or think that Beckett is simply too dark, too depressing, or too strange for them based on those interpretations that, I believe, don't fully represent what has been written.

Thank you for your swift reply, Mackenzie. I agree with you, that Samuel Beckett, not to mention each of the two works cited in your essay, are vast topics. Certainly, people have been discussing, arguing, staging, re-staging, and more over these topics for more than half a century.

It sounds like, while your essay touches upon challenging traditional interpretations of Beckett´s work on the page and onstage, that your thesis is primarily concerned with a literary analysis of "Godot" and "Endgame", versus comparing or contrasting different productions or interpretations of these two texts.

I would be curious to see what questions would arise for you and in this subject more generally, if you were to a) focus on one of these two scripts by the author, and then b) examine a few different versions of that same script. For example, in considering "Endgame", I think a lot could be mined by comparing its first three productions: the 1957 version directed by Roger Blin--in French, but before an English-speaking audience in London; the Alan Schneider production from 1958, at the Cherry Lane in NYC--in English, for an American audience; and then the early 1960s staging of the play, performed in English in Paris, directed by Beckett himself.

Another angle could be examining these stage directions, as well as these plays´ more specifically, between translations. While originally from Ireland, Beckett spent most of his writing / artistic life in Paris, and was a member of the French resistance during WWII. Often, his plays were originally written & performed in French, before he translated them back into English. Some of his stage directions were in original drafts of manuscripts, and some arose through the collaboration of the actors he was working with at the time. The University of Reading (UK), for example, has a number of excellent archival material, detailing these various editions, documenting these changes. Even the title "Endgame" is not a completely accurate translation of the play´s original (French) title, "Fin de partie".

Finally, another angle which could be interesting to explore, based on your essay, are productions that veer away significantly from Beckett´s original (literalized) stage directions, yet arguably retain--or even enhance--the play´s original meanings. I am sure that you are familiar with the JoAnne Akalitis´ (in)famous 1984 production of "Endgame" at A.R.T. (Massachusetts), which featured African-American actors in an abandoned NYC subway platform as its setting; or the more recent site-specific staging of "Act Without Words II", presented in alleyways of Dublin, Tokyo, and London by Company SJ.