In Search of Lost Hope

Theatre Against All Odds in Afghanistan

There is a shortage of global organizations working to secure the rights and safety of performers at risk, especially theatre artists, whose needs are often harder to meet in cities of refuge as they require other artists with whom to collaborate. Despite the excellent work of FreeMuse, PEN, ICORN, freeDimensional, and the Arts Rights Justice EU working group, we need more involvement from the general public and from artists in the free world. Some of the major issues we are dealing with in the field of artist rights and safety include reaching artists in peril, assisting artists to escape home country threats, coordinating placement and host options, supporting threatened artists (including legal, medical, educational, and artistic support), and spreading awareness to arts communities and beyond. This series will highlight the work that is being done around artist rights and safety in the theatre world, in the hopes that we can ignite dialogue, spark further exploration, and encourage more people to get involved in this growing field.—Jessica Litwak, series curator

In the dark times,

will there also be singing?

Yes, there will be singing

about the dark times.

—Bertolt Brecht

I met Hadi, Dr. Sharif, and Saleem in Afghanistan’s capital Kabul within the period of a few weeks in the winter 2007/2008. It was an encounter that changed our lives forever—the beginning of a friendship born in struggle that has since metamorphosed into something akin to brotherhood or even family, with all the intimate trials and tribulations that such relationships of intense living, dreaming, working, and mourning together in the midst of war inevitably entail.

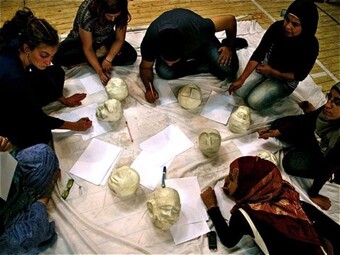

What brought us all together was the theatre. First in the form of two Theatre of the Oppressed workshops with victims of war, and then the adaptation and tour of a play dealing with the long, violent conflict in the North of Ireland, AH6905 by Dave Duggan. The yearning at the heart of our theatre activities was a more just, democratic, peaceful, and beautiful Afghanistan for all Afghans, independent of their ethnic group, sex, or religious orientation, and free of constant interference from false friends near and far. Our morale was one of defiance, outrage, and anguish about what at the time were thirty years of uninterrupted war, the havoc it had wreaked on the lives of millions of innocent people, and a culture of impunity sustained by a global alliance of fundamentalist warlords, both so-called Christian and so-called Muslim, whose insatiable hunger for power and money kept feeding the war machine with the bodies of the righteous.

Yet our spirit was also full of hope and resolve, especially to the extent that our theatre activism began to convert what Dr. Sharif called “tears into energy”; that is to say the process of individual and collective psycho-spiritual (self-)empowerment and political (self-)mobilization that emerges when the grief of having lost everything is embraced by our indestructible capacity to love and support each other, because we understand that this is the only way for us to stay alive.

No desire to open my mouth

What should I sing of...?

I, who am hated by life.

No difference to sing or not to sing.

—Nadia Anjuman

It was in those moments of radical fragility that we realized that another Afghanistan was possible, that the theatre could make a unique and powerful contribution to this possibility, and, perhaps most importantly, that the only people capable of carrying out this endlessly obstructed transformation were those Afghan women and men no longer willing to accept that they were born for nothingness; with trapped wings and a sealed mouth, as slain Afghan poet Nadia Anjuman (1980-2005) so hauntingly wrote.

It was in those moments of radical fragility that we realized that another Afghanistan was possible, that the theatre could make a unique and powerful contribution to this possibility…

The next few years were marked by frenzied, all-or-nothing efforts to create a different Afghanistan in the here and now, on the stage and in the streets, site-specifically and specifically with and for the country’s victims of war and in particular Afghanistan’s widows. Our group of theatre activists quickly expanded, especially thanks to the force added by a number of indomitable women, and we established the Afghanistan Human Rights and Democracy Organization (AHRDO), a political theatre platform that aims to contribute to the creation of a fundamentally different Afghanistan from the bottom-up, employing a combination of emancipatory theatre methods and direct interventions in the public sphere. As a result, dozens of workshops and performances were carried out all over the country, summoning thousands of spect-actors and gradually supporting the build-up of a grassroots movement of victims determined to speak truth to power and demanding more than just crocodile tears in return. Rehearsals for change in the theatre became interventions on TV, demonstrations in central Kabul, and/or the occasional, temporary invasion of an embassy or a minister’s office. Our biggest successes: the official naming of a street in the capital dedicated to Afghanistan's victims of war, and the conviction that things do not have to be the way they are as long as we can continue to come up with the type of collective choreographies capable of rekindling our imagination and reservoirs of beauty after years of vicious assault.

Needless to say, this public unchaining of people’s dignity was often met with the merciless violence of those who enjoy their lives accumulating the miseries of others. Friends and comrades were killed, maimed, or exiled. Uncles, daughters, and sisters were once again shred to pieces. And how many times can a person be widowed without finally losing his/her mind in the labyrinth of insanity? As time went by, the Kabul river overflowed with our tears a thousand times, eventually sweeping away the memories of our victories and leaving in its wake but the voiceless cries of yet another generation of nameless Afghans, “nobodies who are worth less than the bullet that kills them” (Eduardo Galeano).

A basket of sorrow on his back,

he moves wearily through the blades of grass.

—Moh’d Sharif Saeedi

Today, in the spring of 2018, the period of the year when for a very short time Kabul enchants the hearts and souls of friends and foes alike with the smell of thousands of flowers and trees in bloom, emboldening the city’s innumerable poets to give birth to new glimpses of hope and redemption, “despair fills the space in the soul that was [once] occupied by hope” (John Berger). Afghanistan has now been at war for forty excruciatingly long years. That is approximately 14,600 days, 350,000 hours or 21,000,000 minutes, with no end in sight. Quite the contrary: the slaughter goes on and innocent people die every day at the hands of the Taliban, the Afghan army, the Islamic State, the Pakistani intelligence service, NATO troops, or US special forces. There is nothing to say in their defense. They are all the same: they are all murderers and therefore criminals who should be brought before the International Criminal Court (ICC) and receive their long overdue punishment. Nobody is winning. Everyone is losing, though some are certainly losing in more pleasant conditions than others, albeit hopefully not for much longer.

In the meantime, our theatre activism continues and my dear brothers Hadi, Dr. Sharif, and Saleem, aided by a new generation of indomitable Afghan women and men, are still fighting the good fight. The show must go on and methods such as the Theatre of the Oppressed can still provide a “new breath of life” and “a way out” (Alain Badiou) of the tension between dreams and practice. But ten years is a long time when you must rise every morning, not knowing whether you and/or your loved ones will make it until the next day. When you are forced to travel to a theatre workshop on roads controlled by those who will kill you on the spot if they deem your eyes or nose to be those of an infidel. Or when you have to joke or perform in front of an audience infiltrated by people whose blood on their hands never dries and who tell you to immediately stop the performance, otherwise. And what about the time before 2007? The years spent in refugee camps, being tortured with electroshocks or having to tell your mother that yet another of her sons, number six, was killed? Finally, what about being in the midst of a suicide blast that spares you but kills over eighty of your friends, whose dismembered bodies you now have to collect and hand over to their families?

Miscarried dreams

and nowhere to put them,

the river of life listless in its hopeless bed.

—Aimé Césaire

All of this (and much more), my three friends, my three heroes, have had to endure over the course of their lives and yet one of the first things they did in the days after the blast was to organize a theatre workshop with some of those who survived the attack. Surely, it takes a very special kind of human being who, instead of drowning in a sea of sorrow and resignation, puts themselves out there once again and lets solidarity take care of the healing. And yet, the baskets of sorrow on our backs are filling up. What do we do when they begin to wear us down? What do we do when we begin to feel that our sense of disillusionment is becoming irreversible? How do we get up when we have not learned how to fall? How do we encourage the encouragers?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here