Mysticism in the Theatre

What’s Needed Right Now

Mysticism represents the energy which drives, as well as unites all traditional spiritual paths. Mysticism characterizes the singular spiritual yearning at the heart of being. More importantly, mysticism represents the place where all sacred paths are in agreement: it denotes the human religion, shared by all.

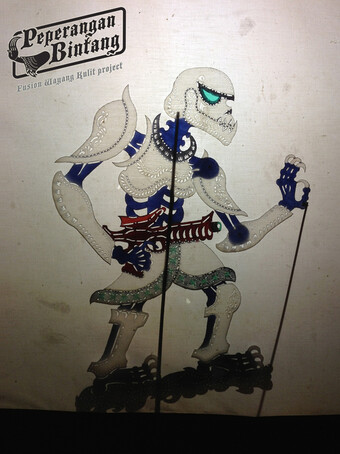

Photo courtesy of Tom Block.

As the great thirteenth century Sufi (Islamic) saint Rumi noted:

Though the words of the great saints appear in a hundred different forms, since God is one and the Way is one, how can their words be different? Though their teachings appear to contradict, their meaning is one. Separation exists in their outward form only; in inner purpose they all agree.

British philosopher Walter Stace proposed two aspects of mysticism that were shared across all cultures, religions, time periods, and social conditions. One defined an experience that “looks outward through the senses” to apprehend the Oneness of all through the multiplicity of the world, comprehending this unity as the consciousness of the world.

A second facet comprised an inward looking experience in which an “emptying out” by a person of all experiential content and phenomenological qualities, including concepts, thoughts, sense perception and sensuous images, leads to a “pure” wakeful consciousness, through meditation or other mental exercises.

As we head into a more difficult and divisive period in American political and social history, a reinvigoration of these ideas represents a much-needed remedy. The energy, ideas, and impetuses provided by mysticism can inspire theatre artists and inform theatrical productions in specific ways, offering a timeless healing energy to the social illness that has burst like an abscess into American culture.

Historically, playwrights have utilized mystical ideals to underpin their narratives, as well as stretch the meaning and intent of their work. Of course, a play like Waiting for Godot (Samuel Beckett), immediately comes to mind, as it takes place in the liminal space of mystical time (where eternity and the temporal meet).

We also find specific mystical references. One example comes from Shakespeare’s King Lear, where the bard presents a world where Purgatory exists, but not the hereafter. Purgatory is here and now. “I am bound/ Upon a wheel of fire, that mine own tears/ Do scald like molten lead . . .” This tracks the mystical concept that physical life is the greatest veil between humanity and the Real—an idea that appears in all three Abrahamic faiths, as well as Buddhism, Hinduism, and other religious paths.

Mystical thought is not currently an important aspect of our social, political, or even artistic conversations. It is often considered irrelevant and even anachronistic in our era: something contrary to the cult of the individual, the yearning after fame and fortune, and the capitalistic anarchy that defines contemporary society. But by reinvigorating mystical ideas through their insertion into living theatre, both mysticism and theatre can become central to a desperately needed social renewal—healing wounds, crossing social divides, and helping to suture the American society back together.

Most, if not all, theatre artists feel a strong spiritual impetus to create their work. They feel instinctually drawn to use their craft to raise awareness of social and political issues, to influence the culture around them with their art, and to better society through their plays.

There are many specific manners in which these ideas can play an important role in theatrical productions. I will outline three of them below. Just as important, at the end of the article, I will include a number of mystical texts from all time periods and many paths, which might offer language, methods, and concepts to influence theatrical writing, lighting, stagecraft, acting, and productions in general.

Photo courtesy of Tom Block.

Inspiration

Most, if not all, theatre artists feel a strong spiritual impetus to create their work. They feel instinctually drawn to use their craft to raise awareness of social and political issues, to influence the culture around them with their art, and to better society through their plays.

However, many of these same socially-driven artists do not consider themselves "religious" per se—they do not draw their inspiration from a particular path or set of religious prescriptions. Therefore, at times, they must draw from the well of social contact, of working with like-minded people, or of simply “knowing” they are doing the right thing, though unsure from where this power within them arises.

Mystical thinking can offer a spiritual foundation for these creators, outside of the narrow halls of the religious edifice. Far from demanding, cajoling, asserting, and threatening—as it sometimes seems that religions do—mystical energy is as soft and yielding as water. Yet, as the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu noted: “For dissolving the hard and inflexible, nothing can surpass it.”

For theatre artists, who feel driven to create for the purpose of inspiring positive social change, the gentle wisdom of great and open-minded thinkers can offer a strong foundation from which to work, while not demanding, exhorting or punishing if certain metrics are not met. What’s more, as Lao Tzu assures, this quiet energy is the exact thing needed to dissolve nagging spiritual questions within the theatre artist, and social walls between people without.

To center one’s work in these ideas, I suggest reading mystical texts, sharing the ideas, gathering with like-minded friends and colleagues to discuss their relevance to the theatre and to society, and generally making the mystical point of view present in one’s life and worldview.

Infiltration

Mystics have been thinking about, dealing with and proposing solutions for the very same social problems (greed, will to power, charity/lack of charity, the demonization of the “other,” etc.) for at least 5,000 years. Their ideas can provide a wealth of material, strategies and even specific language which can influence the creation of theatrical work. These ideas might be woven into plays, dropped into the mouths of characters, illuminating contemporary concerns with timeless wisdom.

The precedence for this infiltration into theatrical productions lies in the history of mysticism itself. In medieval times, liturgical language was embedded into Sufi (Islamic) and Kabbalistic (Jewish) poetry, as a manner of providing little turbines of mystical power. This was called shibbutz, or “inlay,” and originated with medieval Sufi poets using Qu’ranic lines as their spiritual ornament. Later, Jewish mystics borrowed the idea, utilizing Biblical quotes to enliven their mystical poetry.

Photo courtesy of Tom Block.

Theatre artists might borrow from these great thinkers, reading and then inserting the words or point of view of anyone from Lao Tzu to Nelson Mandela, to Gandhi, to the Baghavad Gita into their plays, thereby reinvigorating the mystical concepts in a contemporary milieu. These “inlays” might also add a timeless quality to contemporary social and political problems, situating them more clearly in the stream of human history, instead of treating them as concerns unique to our era. It is important to remember that Donald J. Trump (for instance) is hardly a novel social concern. He represents a political energy as old as bread or beer.

For instance, in my play Sub-Basement (IRT Theater, March 24–April 15, 2017), I lace specific mystical quotes through the text, to highlight the spiritual search of the main character as she struggles, halfway between poetry and the law. For instance, Arnaud, a homeless man, states, concerning his fate as an older gentleman with no means, that he is not afraid of dying: “Death isn’t the end, after all. Just the doorway by which the lover rejoins the beloved,” a direct Rumi quote. His friend responds: “I told you not to read that stuff!” And a bit further along, as the “teaching” of the main character Adrienne devolves into the chaos of her internal state, Arnaud (the designated mystical adept) quotes Rumi again: “Sell your cleverness and buy bewilderment,” to which our beleaguered hero asks why, if he is claiming to offer answers, he just keeps confusing things? He responds with the one of the most important mystical kernels: “It means that sometimes answers lie buried in confusion. In fact, sometimes confusion is the answer.”

These “inlays” also help theatre artists build their projects into spiritual engines, providing impetus for the audience to think in unusual ways as they work to positively influence the world around us. The infiltration into the general public takes place as the words and ideas are woven into the plays, and the ideas are disseminated to audiences.

Specification

Going beyond inspiration and “inlay,” numerous other manners of relating mystical concepts to building theatrical pieces can be explored. Mystical impetus for underlying narrative themes or points of view; for considering set building or sound scores; for acting choices; for discovering novel creative motivations, and numerous other ideas emerge from a consideration of mystical writings and views.

At this point, however, it is vital to point out that I am not proposing a clear and direct expression of these concepts. I do not envision having an actor move downstage and, in a direct address, implore: “As the great Sufi Saint Rumi so presciently queried, ‘can’t we all just get along?!’”

Far from this literal presentation, shibbutz involves subtlety, dexterity, and gentleness in presentation. The audience, in my opinion, should not be able to flag when they are being approached with mystical energy, or even quotes. These should be woven seamlessly into the theatrical presentation, leaving their residue in the memory and subconscious of the audience, as opposed to pounding them over the head with a (metaphorical) two-by-four.

Given this, however, there are numerous approaches by which this mystical inlay might be pursued. As noted, the clearest method is in language use. For instance, in a play of mine (La Bestia: Sweet Mother), I use many mystical quotes, borrowed verbatim from the sources. However, far from being delivered directly and with earnest intent, I twist them in such a way as to cause the audience to consider them more deeply.

These words are put into the mouth of a CIA agent to justify her work in killing what we know to be an innocent woman, a Syrian freedom fighter. By putting quotes from the Baghavad Gita, Rumi, and others into her mouth as justifications for her “vital” work, it shows not only how language can be twisted, but also how these ideals can become subsumed in negative, divisive energy. The implicit message is that these ideals must be considered and implemented in the manner in which they were intended: as doorways into the spirit and toward the appreciation of sameness.

Photo courtesy of Tom Block.

Mystical ideals might also influence set design. Although we’ve all sat in a theatre and seen, as the curtain rises, a perfect representation of the inside of a Starbucks Coffee Shop (down to the little red straws!), mystical impetus would ask us to think a bit more deeply about issues of metaphor, the subconscious, and the quiet messages of the spirit emanating from within.

There is much rich visual symbolism threaded through mystical writings, which might inspire set design to move toward the liminal or interior spiritual spaces, as opposed to a twenty-first century coffee shop. A set designer might consider using the softness of materials to create a welcoming space; a water-theme to echo Lao Tzu’s admonition that “for dissolving the hard and inflexible, nothing can surpass it” or unusual colors (all red, gold, or white for instance) to bring the audience out of the banal and into the world of essence.

I create liminal spaces through the use of my paintings on set. As a longtime visual artist (and playwright), I am able to pair paintings with subject matter to add psychological and spiritual depth to the set design, as well as expand the subtext of the characters. This is another option: to work with a visual artist to help build a novel, world-bending vision of the tableau of the play. These various and strange visual presentations can remove the audience from the banal world of a Starbucks or perfectly rendered hotel room, and indicate that the messaging involved takes place on a different, and deeper plane.

The same can be said of the soundscape, of course. While I certainly appreciate hearing the exact sounds of the street, a period streetcar, or the interior of a bar (“I know which one that is!”), I feel that sound—like the set, language, and all aspects of the play—should help remove the audience from the banal to consider deeper issues, and how they can affect our interactions.

Photo courtesy of Tom Block.

Mystical and spiritual ideals…offer a vital and fresh manner of reconceiving possibility, approaching the audience beyond their conscious thought.

Every playwright and design team will define their own manner of doing this. Personally, I like to work with live music, and specifically the cello. A good cellist can not only interpret and interact with the language and actors, but also deepen the tone of the piece’s meaning.

Mystical and spiritual ideals are “timeless” because they relate in a very specific, though different manner to every time and place in human history. Although they are not much considered in today’s theatre world, or any other facet of society (not even religion!), they offer a vital and fresh manner of reconceiving possibility, approaching the audience beyond their conscious thought.

A Sufi saying holds: “Words spoken from the mouth will never get past the ears. Words spoken from the heart, enter the heart.” Now more than ever, our task is clear: theatre artists must speak from the heart, so our audiences can “hear” with the most important sense organ we have: the heart.

Suggested Reading List:

Aurelius, Marcus: Meditations

Baghavad Gita

Berry, Wendell: Standing by Words

Black Elk: Black Elk Speaks

Buber, Martin: Tales of the Hasidim

Buddha: The Dhammapada

Chuang Tzu: Genius of the Absurd

Eckhart, Meister: Selected Writings

Gandhi: All Men are Brothers

Heschel, Abraham Joshua: God in Search of Man

Huxley, Aldous: The Perennial Philosophy

Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching

Mechthild of Magdeburg: The Flowing Light of Divinity

Merton, Thomas: Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander

Rabi’a: Rabi'a the Female Mystic and Her Fellow-Saints in Islam

Rumi: Rumi and Me (William Chittick, translator)

Sheikh Sa’adi: The Rose Garden

Sogyal Rinpoche: Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

Weil, Simone: Waiting on God

Yeshe Tsogyel: The Secret Life and Songs of the Lady Yeshe Tsogyel

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I think shamanism is a better spiritual path for theater artists than transcendental mysticism. Shamanism is the exploration of the human psyche to discover the deeper truths within ourselves. The shaman goes on a vision quest to visit the spirit-world, the psyche, and returns from the other world with wisdom that is to be shared with the tribe. It is important to note that the very first actors were shamans, performing rituals for their tribe. The key to shamanic practice is the visionary experience and this can be obtained through trance or Jungian active imagination which is quite similar to the process of writing a play.

Strangely, there are few books on the relationship between shamanism and theater. I've obtained most of my knowledge on the subject from depth psychology and comparative religion. But I recommend the following:

"Shakespeare's Royal Self" by James Kirsch. A rare example of Jungian analysis applied to drama. The author analyzes Hamlet, King Lear, and MacBeth.

"Sacred Play: Soul-Journeys In Contemporary Irish Theatre" by Anne F. O’Reilly. This is probably the best book on how drama is the process of "soul searching" but you have to read a lot of contemporary Irish plays to follow her meaning.

"The Way Of The Actor: A Path to Knowledge and Power" by Brian Bates. This book explains how the actor functions as a shaman.

There is a lot of literature on aspects of shamanism which relate to theater; ritual, initiation, unconscious symbolism, etc. But I've never found a book that really ties it all together or packages it for the theater artist so you have to do a lot of reading and thinking to see how to apply it to your work.

Robert, thank you! Fascinating insight. I have a dear friend I have worked with, James Leonard, who has created a climate change divination tent, in which he gives climate change Tarot readings to querents. It is called the Tent of Casually Observed Phenologies, and offers an interactive, audience-centered vision along the lines you are talking about. You can get a sense of his work here: http://jamesleonard.org/work/

Now, I love Jung. I definitely do, and I love the work you are bringing to light for us, but I would hesitate to say that shamanism is "better" than other spiritually-centered manner of using theater to open audiences to different levels of reality. As Huxley notes so clearly in The Perennial Philosophy, there are many paths up the mountain, but they all lead to the same place. I, myself, know very little of shamanism and look forward to exploring some of the materials you have brought to light. But I would hesitate to say that I will abandon one path to follow another. However, I definitely look forward to exploring, expanding, adding to and finding specific and applicable theatrical inspiration from these works.

Many thanks, Robert -- though I do find the skull just a tiny bit scary. But that's the point, right? We must face our fears to overcome them.

Tom

P.S. Simone Weil said: "Where there is a need, there is an obligation." If you've "never found a book that really ties it all together or packages it for the theater artist," perhaps that's because it's for you to write?

I'm familiar with mysticism and enlightenment but it is not useful for the artist because you transcend the need to create art. Once you've risen above your ego you no longer feel the need to communicate with others. I can totally free myself from social consciousness but without that I no longer want to engage with the world. Shamanic practices actually seek something more closely akin to artistic inspiration. Check out the Wikipedia entry on "Artistic inspiration" and find the definition "In Greek thought, inspiration meant that the poet or artist would go into ecstasy or furor poeticus, the divine frenzy or poetic madness. He or she would be transported beyond his own mind and given the gods' or goddesses own thoughts to embody."

One of the oldest plays that has been interpreted as being shamanic is "The Bacchae" by Euripides. The shamanic elements in "The Bacchae" have been noted in the books "The Greeks and the Irrational" by Eric R. Dodds and "A Jungian Approach to Literature" by Bettina L. Knapp. This is relevant because Western theater can be traced back to the worship of the Greek god Dionysus, the god of wine and divine frenzy or poetic madness.

Robert, thanks -- and I love the image of "furor poeticus, divine frenzy and poetic madness," though I've never had the pleasure of experiencing such a thing. I'm more of "the muse only visits the artist who keeps regular office hours" type of creator.

Your information is powerful, well-considered and very interesting. I can't wait to read your book on the subject! Or your essay.

All my best,

Tom

What the heck, I'll give it a go, as well. I define mystic or mystical (in the timeless sense, going back through all traditions to the beginning of human spiritual yearning) as the basic impulse to empty oneself of all but the universal force (known to many as "God"), as well as appreciate the unity of all, lying hidden beneath our experience of diversity. Aldous Huxley wrote a beautiful book which explores the mystical tradition at the heart of all religions called "The Perennial Philosophy."

In terms of the theater, I actually agree with Nick. I have done many mystically-inclined paintings, and certainly there was an era of human history when painting was the most important manner of expressing spirituality, but I think in our era it has waned in its efficacy. The theater offers the immediacy of true human contact, plus the metaphorical vessel to remove people from their day-to-day lives, all while engaging audiences on many levels, through many senses.

I have a play coming up next week (Sub-Basement, opening March 23rd at IRT Theater in NY: http://irttheater.org/3b-de... which puts into practice the theory I wrote about in this article. Specifically:

Language taken directly from mystics (in this case "Rumi") "Sell your cleverness and buy bewilderment" and "Death is the doorway by which the lover rejoins the beloved."

Ideas taken from classical mysticism: "...sometimes answers lie buried in confusion. In fact, sometimes confusion is the answer." This echoes Martin Luther (Christian), Attar (Sufi/Islamic), Maimonides (Jewish) and many other mystical thinkers.

Circular time as a representation of eternity

Liminal/metaphorical space

If you get the chance to see it, I'd love to know what you think!

Tom

A beautiful response. I would add something I just read from a truly inspiring book 'The Secret Tradition of the Soul' by Patrick Harpur, who also wrote 'Daimonic Reality' (a pertinent book for theatre creators). It's a quote or rather part of a quote from Heraclitus pertaining to Soul (and which I would say is applicable to the mystical) "there awaits us what we neither expect nor even imagine."

All the best with your play Tom. I'm just outside NYC and will check out you link and make an effort to see it..

Michael, that's great! And FYI, I'll be in the house March 24, 25, 26 and 27 -- please make sure to say hi, if you come during that time!

Tom

Interesting thoughts, Tom. And I like the idea of including more mystic sensibilities in the theater.

I'm curious, though, for your response to two questions: how exactly do you define "the mystic" yourself (as opposed to other religious traditions)? And do you think that theater's transitory nature makes it more able than other art forms to embody the mystical?

Thanks in advance for your thoughts!

I'll certainly chime in with my perspective on these questions. I would define 'mystic' as something seen and/or heard that evokes an internal response within the recipient which activates a feeling and awareness of possessing some combination of the following qualities: spiritual numinosity, mystery, awe, sacredness, transcendence, depth, vastness, profound silence, unity, deep or expansive insight beyond the ordinary, bliss, love. The list could go on.

Regarding second question. I don't think the transitory nature of theatre necessarily embodies the mystical more fully than other forms. Certainly the Mona Lisa radiates mystical qualities, luckily for humanity, in a form that does not disapate through the ages. However, the nature of life theatre, with its living presence in the moment, can radiate the mystical in a uniqely powerful way. I still remember the cellular quivering of my body and mind during the final moments of watching the play Jerusalem. THAT was one neck of a mystical experience in the theatre.

I've long considered mysticism an integral part of the theatrical experience; that is, when things are just right, and the actors are completely connected with their characters and drawing energy from an enraptured audience, it's as if the performers have indeed channelled the spirits of their characters, and in so doing facilitated the connection of everyone present to the source from which we all come.

Neal, thanks for this -- and mysticism does take many forms. The synergy of a successful production, built quickly (over weeks, not years), yet creating relationships which might appear to have been developed over years or decades, definitely edges into the territory of the unspeakable.

Thank you for this important, relevant and beautiful article. We live in times where the abnormal is promoted as normal, where lies are promoted as truth. Thus the contribution of mystical perspectives within theatrical presentations, whether imbedded with subliminal subtlety or in more direct ways, served a larger context. Unfortunately I don't see much in contemporary theatre that seems interested in seriously considering that larger context. Part of the challenge with this inclusion involves the nature of drama itself, which is reliant on the fundamental dynamic of conflict. Mystical insight, represented through various writings through the ages, offers the awareness and guidance of moving into territory beyond the intensity of conflict, where ordinary consciousness resides, to the domain of unity. The mind set for many is conditioned and addicted to 'more.' More novelty, more violence, more sex, more disruption, more spectacle, in essence more chaos. How to bring the energy of mystical relevance (the theme of unity) into the fundimental structure of conflict within dramatic story telling in a way that engages and moves the audience to considerations beyond the ordinary to a more expansive view is worth contemplating. Certainly this issue was of personal importance in the undertaking of writing my play 'The Bright Darkness' (on the New Play Exchange website). Of course there is space and necessity for all manner of plays, and creating more avenues for and expressions of mystical inclusions could very well be a needed, healing balm for our times.

Michael, thank you so much for your considered comments. In terms of mysticism v. conflict, I have often pointed out (as we move into more a divisive social and political situation here in the United States), that mystical thinking becomes even more important during conflict. Many of the greatest mystical thinkers thrived during times far worse than ours: Meister Eckhart (d. 1328), a great Dominican mystic and (according to the church) heretic, worked at the height of the Bubonic Plague; Rumi and Attar, 13th-century Sufi thinkers, both had to contend with the Mongolian invasion which overran Persia and their homes, and Aldous Huxley wrote his seminal mystical overview "The Perennial Philosophy" in the lead up to and beginning of World War II.

As such, mysticism can definitely (I believe) thrive within conflict, and as a foil to it, even on the stage. Whether it is mystical ideas placed in the mouths of characters (running contrary to more worldly ideas expressed from other characters) or the use of various scenic or design tropes which highlight conflict through their own gentle acceptance, these ideas most definitely have a place within the living theater (I believe).

In fact, mystical ideas -- as they, by necessity, conflict with the accepted objective narrative -- are by their nature oppositional to "normal" modes of thinking. I'm just reading "The Cost of Discipleship" (Dietrich Bonhoeffer) as research for a further post on HowlRound and came across this statement about mystics: "The disciples are strangers in the world, unwelcome guests and disturbers of the peace. No wonder the world rejects them!"

Conflict is natural to the mystical way of thinking, and can most definitely become part of a theatrical presentation based in "more violence, more sex, more disruption, more spectacle, in essence more chaos."

Where better to place a mystic, than in the middle of all of that!

With all my best,

Tom

I agree with you.